This year’s Budget included the Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) reform package, which will have a significant impact on superannuation. One reform, a performance test, has proven highly controversial. A performance test sounds like good policy to protect consumers, so why is it proving so controversial?

This article uses some of the findings from a collaborative research effort between The Conexus Institute and five leading industry consultants: Frontier, JANA, Mercer, Rice Warner and Willis Towers Watson. The detailed research (papers and models) can be accessed here.

The performance test explained

The YFYS performance test works as follows:

- Over a rolling 8-year period the performance of each fund is compared against the performance of a tailored benchmark based off that fund’s strategic (i.e. long-term) asset allocation through time. The benchmarks are all public listed market indices. This could be considered implementation performance, capturing the sum of how well each portfolio position performed against a benchmark as well as the performance of any short-term (tactical) asset allocation calls.

- Initially if a fund fails the test (underperforms by more than 0.5% pa), it needs to write to its members to advise it has been identified as an underperformer, and provide details of a to-be-developed Government website which will detail performance and fees for the universe of super funds.

- If the fund fails for a second consecutive year, it is no longer able to accept new members until the fund passes the performance test. The fund can continue to accept contributions from existing members.

This sounds reasonable, so what is the problem?

The concept of a performance test is good policy. Done well, it helps protect disengaged members from sub-standard outcomes from super. Government and Treasury are simply following a recommendation made by the Productivity Commission.

But the devil is in the detail: the performance test has important shortcomings. Additionally, there are concerns that the way the test is applied will likely leave some consumers worse off.

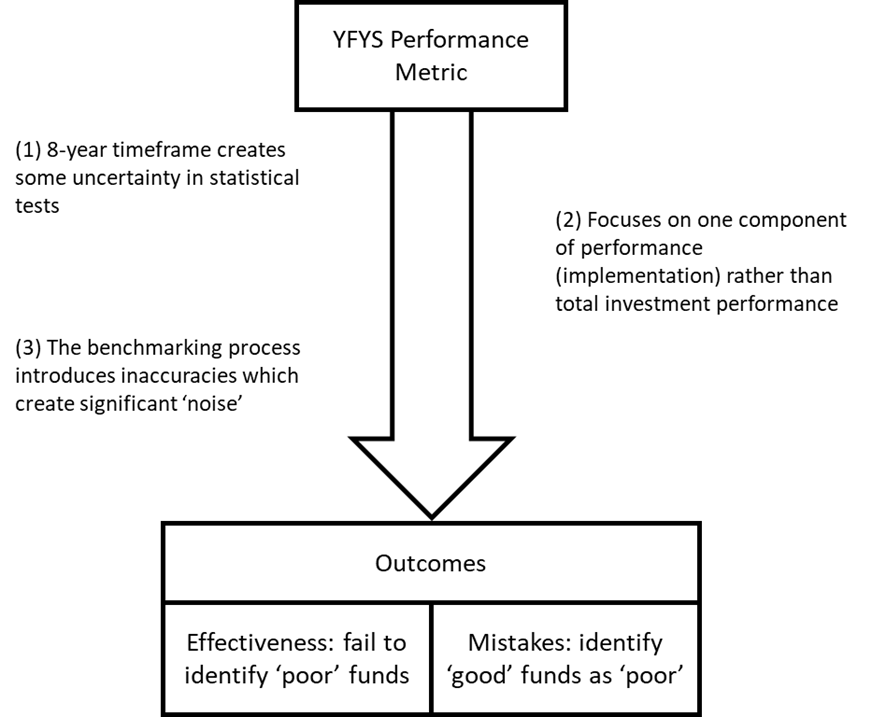

We found three main issues with the test, summarised in the following diagram.

(1), (2), and (3) combine to make for an ineffective performance test.

Here's how to understand (2) better: implementation is an important part of total performance but the asset allocation decisions made by funds are just as, if not more, important. Yet the test ignores the performance of asset allocation decisions. To illustrate, if your fund had made the decision to have 10% more allocated to global shares than to Australian shares over the last 10 years, this would have added more than 0.4% pa to performance. A performance test should capture this component of performance.

The benchmarking challenges noted in (3) impact the assessment of many asset classes including private equity, unlisted property and infrastructure, credit, inflation-linked bonds, and the entire universe of alternative investments.

For example, unlisted property is benchmarked against listed property and there can be huge dispersion in performance between the two sectors which may unduly impact the performance test result at a particular point of time.

In some cases, we calculated that the test would have a very low likelihood of correctly identifying poor performers (likelihood levels akin to a coin toss) while having a reasonable probability of mistakenly identifying good performers as poor.

Finally, none of this acknowledges changes that funds have made to improve themselves, sometimes in response to issues raised by APRA.

Ineffective plus undesirable outcomes

Not only is the test likely to prove ineffective, but we anticipate a range of undesirable outcomes. We summarise these into three categories:

- We believe the test will distort the way that funds will manage their investment portfolios. This test will likely be binding compared to other policy and regulatory tools such as APRA’s Heatmaps, the Outcomes Assessment Test and the sole purpose test. The flaws in the test mean it does not align well with the broad investment management principles of focusing on total returns and diversification.

- We believe consumers will be confronted with a range of complex and potentially conflicting information. Many will find making a choice difficult and the heavily disengaged may be left in impaired super funds and experience worse performance (because the fund is further impaired).

- The focus by industry on the performance test may deter fund mergers. The ‘senior’ fund may not want some of the assets, a membership profile in outflow, nor the distraction that comes with merging with another fund.

Agents, politics, and policy

Unfortunately, superannuation has become highly politicised and some observers view the industry as self-interested agents. Yet strong engagement can contribute to better policy, while poor engagement increases the risk of policy mistakes. Effective engagement requires the trust between policymakers and industry to be strong. Undoubtedly there is room for improvement, but I see both policymakers and industry aligned in their focus on improving member outcomes.

It is good to see that there will be consultation on the performance test and hopefully it is constructive and positive.

Developing an effective performance test is a great opportunity to improve superannuation outcomes for consumers.

David Bell is Executive Director of The Conexus Institute, a not-for-profit research institution focused on improving retirement outcomes for Australians. This article does not constitute financial advice.