I am often asked about my outlook for biotechnology in light of how rapidly vaccines were developed for COVID-19. I say this may be a sign of things to come for the industry. I’ve seen a renaissance that’s led to an explosion of novel drug targets in recent years. The industry pipeline is relatively full for both small and large drug companies across the world, and if some of these developments take hold, this could fuel growth over the next decade.

These are some of the trends:

1. Faster drug development

It is possible in certain circumstances to go much faster in developing drugs than people previously thought. The accelerated approval pathway that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) used for the coronavirus vaccines has been in place for some time, as well as at other regulatory agencies around the world. Europe, Japan, China and others have similar mechanisms that make it possible to move more quickly, particularly when the unmet need for treatment of a disease is high.

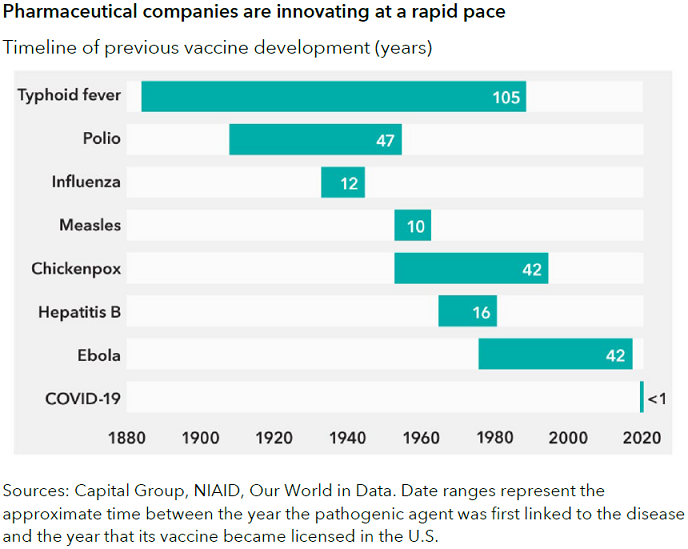

As shown in the chart below, the speed of vaccine development has reduced significantly over time. In the case of COVID, we received the virus’ genome sequencing in January 2020 and had authorised vaccines by the end of the year, which is just stunning.

It may not be possible to do that again for another vaccine, unless there are billions of dollars of government funding that allow companies to assume all the risks in parallel and move as fast as possible. But since the pandemic, companies are collaborating in ways that we haven't seen before.

2. A focus on infectious diseases

Infectious diseases are among the primary sources of illnesses around the world, yet this was an underfunded corner of drug discovery research. When it came to funding and deals between large and small companies, it used to rank near the bottom of the list.

It's now second only to oncology in terms of the attention and funding it is receiving when it comes to mergers and acquisitions, venture capital and private equity investments. Many of the bigger problems are now being tackled with substantial investments.

3. The next big horizon of innovation of cells and genes as medicines

We’ve seen three big phases in the history of medicine. For about 200 years, treatment was by chemicals that we could make in a reproducible way. Most of our newest and best medicines came from factories. Then, in the 1970s, we learned how to make proteins in a reliable way in a factory rather than, for example, extracting insulin from cows to use as medicine. That was the era of biologics. It began first with monoclonal antibodies. The next generation of those are more engineering-specialised antibodies.

And the third big horizon is cells and genes being used as medicines, though we are only at the beginning of this. It holds the promise of both (a) functional cures of diseases that we couldn’t treat at all (or not very well) with chemicals or proteins and (b) one-time treatment rather than chronic therapy for the rest of a patient’s life.

So far, cell or gene therapy products approved by the US FDA are being used to treat cancer, eye diseases and rare hereditary diseases. In the future, the hope is to move into more common diseases too.

The pipeline is growing, with more than 360 such therapies in development in the US, targeting a range of diseases. There’s also a large pool of eligible patients who technically could receive these therapies. However, cell and gene manufacturing are both relatively new, much more complex and expensive than protein or chemical manufacturing, so this adds substantial risks.

4. China is rapidly moving up the innovation curve

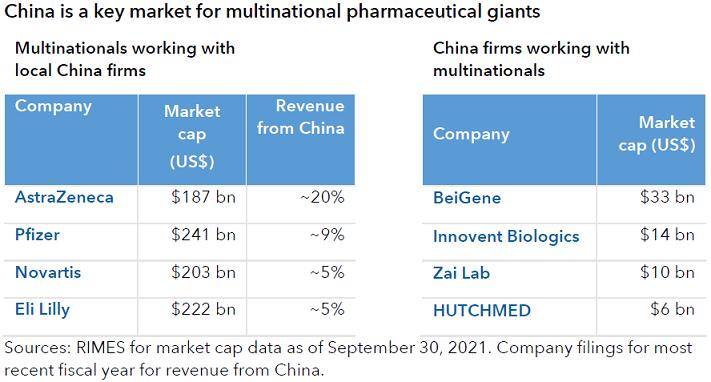

I would highlight the role of China in the global biopharmaceutical industry in two ways: It is the world’s second-largest end market after the U.S. and growing rapidly. It is also a source of globally relevant innovation.

China's version of the FDA has become increasingly more like its U.S. counterpart, in that they have adopted some of the same practices for how they make decisions. Regulatory officials changed some of the technical standards to be more in line with Europe and the U.S. There is a little bit more alignment in the process. They have started to triage applications to deprioritise old undifferentiated types of drugs and focus on newer drugs.

China had a proliferation of undifferentiated old generics, but the government is showing it is willing to pay for innovation, and that is the carrot for companies to keep investing in it. Since 2015, Chinese authorities have pushed policies that encourage and incentivise domestic companies to compete with global companies. In that sense, biopharma is a little different than other industries in China that have been flagged as potentially being the next in line to come under heightened regulatory scrutiny.

5. Harnessing the human immune system to treat diseases

Oncology was the first area to see this concept succeed beyond diseases of the immune system itself, and drugs like Merck's Keytruda and Bristol-Myers’ Opdivo have become one of the largest categories in oncology. But we are only just beginning to scratch the surface and figure out how we can harness the human immune system to manage other diseases.

The idea of understanding the immune system better and harnessing that to potentially intervene in other diseases has been gathering a lot of momentum. Immuno-oncology, which is the study and development of treatments for cancer that take advantage of the body's own immune system, is one of those areas.

Drug discovery is more global than ever before

Research is happening at both the bigger and smaller companies. Big companies are very deliberate in how they balance their priorities, where they source innovation, internally and externally. They can source ideas from academic labs and tiny companies, and they buy small and midsize companies all the way up the chain.

The number of small- and midsized companies has grown dramatically. The amount of venture-capital funding for life sciences broadly, and biotech pharma specifically, has also soared. It is the smaller companies that take the biggest risks and work the furthest out on the leading edge and most novel ideas. And then, as they get a little bit of validation, either through animal models or early clinical data, start to partner with big pharma companies as well.

Innovation is happening in all geographies. It’s not just Cambridge in the U.K. or the San Francisco Bay area. In China, for instance, there are many small emerging companies working on new areas of biology. It’s important to have a global and bottom-up research approach to finding the best value.

Laura Nelson Carney is an equity investment analyst at Capital Group. Capital Group Australia is a sponsor of Firstlinks This article contains general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Please seek financial advice before acting on any investment as market circumstances can change.

For more articles and papers from Capital Group, click here.