The real estate industry, traditionally characterised by its cautious adoption of new technologies, is now at a pivotal juncture. The emergence of AI, with its open-ended and self-evolving nature, promises to fundamentally change the way we live, work and play.

Investors, managers, and occupiers find themselves sitting atop mountains of data, proprietary and third party, about properties, communities, and market dynamics. This wealth of information can be harnessed to tailor AI tools for real estate-specific tasks. Imagine lightning-fast identification of investment opportunities, efficient analysis of ESG data, revolutionary building and interior design, personalised marketing materials, and seamless customer journeys. The potential value creation is staggering with estimates suggesting that AI could generate between $168 – $275 billion for the real estate industry1.

AI adoption

AI has been transforming a range of industries from financial services to healthcare, revolutionising processes, enhancing decision-making, and creating new opportunities. Currently, it is mainly used to streamline processes, improve accuracy, and enable data-driven decisions. Some examples include:

Automated content creation: AI systems proficiently generate content, including emails, articles, and press releases. For instance, AI-powered tools can draft initial investment memorandums, providing a solid starting point for further refinement.

Legal document drafting: Litigation-related disclosure obligations were a gateway for AI to enter the legal world by transforming mass document review and enabling greater standards of compliance. Law firms now also leverage AI to draft legal documents, such as sale and purchase agreements and lease summaries. These AI systems analyse existing templates, extract relevant clauses, and generate customised contracts, streamlining the legal process. Law firm BCLP has used AI to develop a lease reporting tool which the firm claims will save its employees 25% of their time2.

Predictive analytics: AI algorithms analyse historical data to predict market trends and property values. Real estate professionals can make informed decisions based on these insights.

Virtual assistants and chatbots: AI-powered virtual assistants handle inquiries, schedule property viewings, and provide property information. With regards to leasing and property management, a case study from Elise AI claims they were able to increase their conversion rate by 112% and increase appointment bookings by 317%, whilst saving on average two hours each day3.

The real estate industry has accumulated vast amounts of data. Historically, there have been persistent questions regarding how to efficiently analyse this data and leverage it for research, operations, and investment management.

Now, with AI and AI-powered tools, we are witnessing a transformative shift. For example, AI enables organisations to efficiently track, analyse and report on ESG-related data, which is crucial for making informed decisions and meeting regulatory requirements. A KPMG survey stated that 58% of organisations plan to improve ESG data collection using AI4.

Shifting occupier markets

A less discussed perspective is AI’s potential influence on occupier behaviour and how their space usage and demands may evolve. Understanding shifts in occupiers’ location, asset type and amenity preferences is crucial to optimising allocation decisions and driving investment returns.

1. Offices

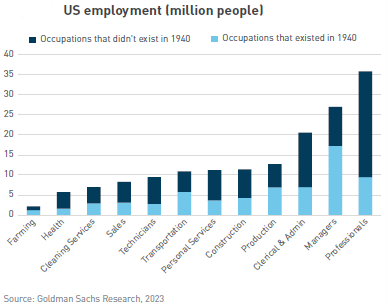

One of the key concerns regarding AI and office markets is the prospect of automation displacing swathes of jobs, reducing demand for space. After all, ChatGPT doesn’t need a desk! But the long list of examples through history of technological advancements and their impacts on the workforce show the reality is generally multifaceted – some jobs are displaced, others are altered, and many are created. Analysis of US employment finds that 60% of workers today are employed in occupations that didn’t exist in 1940. While AI-related net job losses are possible, the historical experience and adaptability of society over time suggests economic and employment growth is the more likely outcome of AI-related innovation5.

However, the composition of the labour force and the nature of many roles are likely to shift significantly. While the capabilities of AI have improved dramatically, it is still well suited to repetitive tasks with well-defined parameters such as data analysis, administrative reporting and assisting in content creation6, but is less proficient than humans when it comes to relationship management, innovation, and strategic decision-making. As AI shoulders a greater load of the ‘grunt work’, humans will be able to allocate more of their time to high value tasks that are interpersonal, collaborative, and complex in nature. For example, a software engineer may spend less time programming and more time understanding client requirements and discussing solutions.

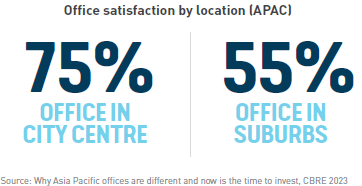

A shift in the balance of tasks could see the nature of roles become more suited to a collaborative environment and reinforce preference shifts and space usage changes that have occurred since the pandemic. The purpose of the office has shifted towards performing human-centred, collaborative tasks7, while workers are undertaking more of their ‘focused’ tasks at home. Occupiers are therefore prioritising centralised, rather than distributed or satellite locations8, to maximise in-person interactions. This is supported by a greater proportion of office footprints being allocated to collaborative and activity-based working environments, such as meeting and conference rooms, stand-up areas, and communal spaces rather than desks9.

Organisations will continue to strive to make their office footprint as efficient as possible, a trend which has been underway for decades. Dynamic desk management can be used to coalesce employees and reduce energy consumption where desks aren’t being utilised, with AI providing additional “smarts” to further optimise existing systems. This kind of management system is more likely to be adopted by larger occupiers, given their workforce and office floorplate can be more easily flexed, and they have a greater propensity to rationalise their footprint, compared to smaller occupiers.

Ultimately, the ingredients for success will remain largely the same. Assets in the best central locations, offering diverse amenity and high-quality space for a suitable price, will outperform those that are less aligned to the preferences and needs of occupiers.

2. Logistics and industrial

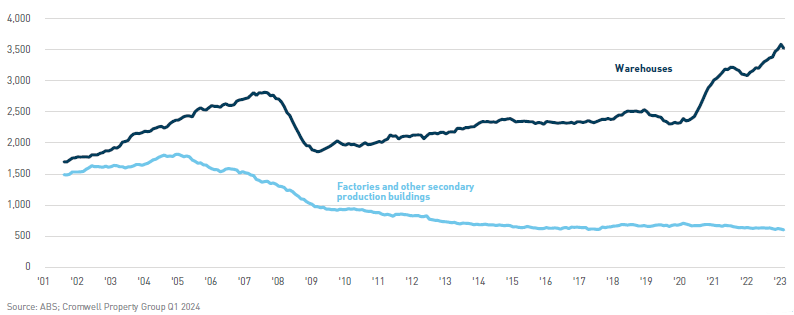

Many occupiers are already leveraging AI in their facilities, for example by using intelligent autonomous robots to store and pick items, or by calculating optimised routes for human workers trying to navigate thousands of products. Given the pre-existing utilisation of automation and AI, we don’t foresee recent advancements driving major changes to occupier space requirements at the asset level. However, it may drive a proliferation of automation adoption, and a more rapid replacement of ageing stock which is not fit-for-purpose, for example due to inadequate slab strength or larger power requirements.

We expect the most significant implications for logistics and industrial assets will stem from improvements made in supply chain management. Demand forecasting, inventory requirements and transport routes can all be enhanced by AI’s ability to process vast amounts of data across various formats in real-time and advise accordingly, enhancing resilience and service9. This could lead to footprint rationalisation, whereby occupiers prioritise large, centralised warehouses combined with smaller urban logistics units in close proximity to customers, with less reliance on medium-sized, intermediate facilities as they can better predict demand. This type of model, which historically would have been challenging due to its complexity and inability to respond to local supply or demand shocks, could provide the scale and control benefits of a centralised hub, with the agility and speed-to-customer of last mile fulfilment.

An important byproduct of a more intelligent and efficient supply chain is cost reduction. The pandemic highlighted the shortcomings of global supply chains; however, most are still aligned to the lowest cost countries. If the cost of logistics falls, or efficiency improves significantly, this could alter the cost-risk trade-off and encourage more occupiers in developed economies to onshore a greater proportion of operations, boosting industrial real estate demand.

It is worth noting that ‘industrial real estate’ is a broad term. Not all occupier types will engage with AI in the same way or see the same outcomes. The strengths of AI suggest the biggest changes will be experienced by logistics-focused occupiers, managing the complex movement of materials and products across multiple markets at scale, particularly via standardised big-box warehouses. In contrast, light and medium industrial uses often incorporate both logistics and manufacturing elements. These occupier types, particularly those of smaller scale, may continue to be more reliant on human input and see little change in their operations. This part of the market continues to be more fragmented than ‘big box’ logistics and has witnessed less of a supply response, offering some compelling opportunities for investors.

Number of Australian industrial building jobs approved (rolling 12 months)

3. Retail

In retail, physical and digital channels continue to converge. Retail stores strive to match the low friction and ‘endless aisle’ online experience while e-commerce platforms endeavour to offer the product trial and social interactivity available in person. Outperformance is accruing to omnichannel retailers as a result10.

While not everything can be replicated, we expect AI to further narrow the gap between shopping channels. AI will improve e-commerce product discovery by delivering personalised recommendations and engaging conversations with digital shop assistants. Virtual product trial will improve as augmented reality and AI technology combine to showcase furniture in your own home, or a new outfit as you move around. In the physical world, friction will be reduced as checkout-free shopping becomes more ubiquitous and shoppers are guided individually through malls and shops.

CASE STUDY

In Australia, major supermarket chain Woolworths has started opening micro fulfilment centres attached to stores. Called eStores, these sites have a normal retail shopfront accessible to the public, as well as a mini warehouse or dark store which can efficiently fulfil online orders for the surrounding catchment.

Like the industrial market, we expect these shifts to lead to a bifurcation of retailer footprints and performance. The success of a physical retail store in an AI-enabled world will require having a genuine point of difference and leveraging inherent strengths which cannot be replicated online.

At the discretionary end of the market (i.e. major malls), this means providing tactile, immersive social experiences – being a leisure destination for people to connect, rather than just shop. Typically, larger assets with leading brands and the latest store formats, a night-time economy and higher foot traffic volumes are better placed to succeed in this experiential segment of the market.

For convenience-oriented centres, the value of an asset as a last-mile fulfilment node will become more important, in addition to its strength of connection to the local community. Sites that can double as a retail shopfront and local fulfilment centre, with proximity to customers, access to transport networks and a conducive physical structure and land envelope, will be preferred.

In this environment, middle-market assets that don’t lead on an experiential or convenience basis and lack the community-centricity of a smaller asset may underperform. A key challenge for assets in general will be evolving the retail offer to match the pace of technological change – and effectively managing the resultant capital expenditure.

4. Enabling Infrastructure

While many of the non-traditional real estate sectors will be influenced by AI, data centres are clearly the most intertwined. The explosion of data storage and computing power required to leverage AI will likely mean greater demand for data centres. As low latency becomes more critical for some use cases, there could also be a shift towards edge data centres, potentially resulting in the creation of new markets closer to end users (e.g. mining in Port Hedland, Australia).

A key constraint in delivering the required new supply will be power. This is already an issue across the sector, and some markets have implemented soft or hard caps on development to protect the energy grid and maintain supply for other uses. These supply restrictions benefit existing asset owners, but limit those seeking to capitalise on AI tailwinds. The power and cooling requirements associated with AI exceed the capabilities of many current assets, meaning there will be heightened demand for new developments, skewed towards less crowded markets with more attractive energy costs and access11.

1McKinsey & Company, 2023

2Legal futures, 2024

3Artificial intelligence – implications for real estate, JLL, 2023

4ESG survey, KPMG, 2023

5Future of Jobs Report 2023, World Economic Forum, 2023

6Australia’s Generative AI opportunity (Tech Council of Australia & Microsoft, 2023)

72023-2024 Global Workplace & Occupancy Insights (CBRE, 2023)

8Asia Pacific Live Work Shop Report 2022 (CBRE, 2022)

9The Role of AI in Developing Resilient Supply Chains (Cohen & Tang, 2024)

102023 Inside Australian Online Shopping (Australia Post, 2023)

11Artificial Intelligence: Real Estate Revolution or Evolution? (JLL, 2023)

Colin Mackay is a Research and Investment Strategy Manager for Cromwell Property Group. Cromwell Funds Management is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is not intended to provide investment or financial advice or to act as any sort of offer or disclosure document. It has been prepared without taking into account any investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Any potential investor should make their own independent enquiries, and talk to their professional advisers, before making investment decisions.

For more articles and papers from Cromwell, please click here.