It's a turbulent market environment. The S&P 500 Index and the U.S. economy have defied consensus pessimism this year. Investment hype surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) has gone manic. Europe’s war keeps escalating. The Wagner Group’s revolt could be a sign of even more instability. Climate change anxiety has been ramped up by the Canadian forest fires. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has tried twice this year to support oil prices and failed. China’s reopening has been underwhelming. The U.S. is facing massive budget deficits as far as the eye can see and a contentious presidential election race. The free market era of Thatcher/Reagan-ism has given way to populist political tribalism, big government, and industrial policies.

Handicapping the investment implications for any one of these developments is a major task. But for now, we still believe that the thing that matters most is inflation, despite all the noise.

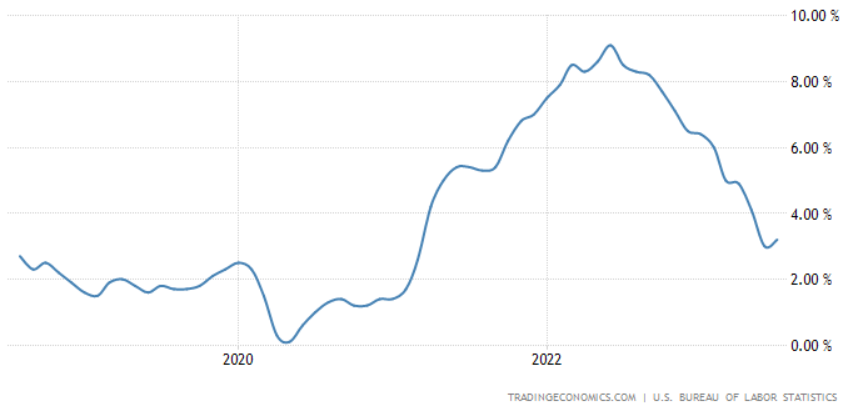

Inflation has fallen a lot in the U.S. Optimism that it will keep falling is what has supported risk assets. We think it is going to keep falling, too. But the decision-makers at the Federal Reserve (Fed) are not convinced. Their job is to keep inflation on target. They believe policy rates and the unemployment rate need to go higher in order to push inflation back to target.

United States Inflation Rate

No one has the inside track on the inflation outlook, especially the Fed. Its credibility eroded, this is the same group of people who did not believe inflation could rise and remain as high as it did in 2022. Now they think it cannot fall without more pressure despite the second most inverted curve in history, the collapse in money supply and credit growth, and the disintermediation underway in the regional banking system. The Fed might be right but the justification for its viewpoint is mainly the inflation rate itself and the low level of unemployment. This stance implies no change in view or policy until after inflation has fallen, as was the case after inflation rose. And it is not just the Fed. Its perspective is the orthodoxy these days among western central bankers and high-profile economic commentators: higher for longer on rates.

Inflation is set to ease

Our view on inflation is more optimistic because:

- The financial and monetary variables point in that direction.

- Inflation is the final piece in a falling line of dominoes. What went up in 2020 and 2021—cryptocurrency, commodities, real estate, economic growth, and inflation—have retreated in perfect sequence starting late 2021 and early 2022. Now it is inflation’s turn.

- We believe keeping conditions tight until inflation has receded to target is a strategy for overshooting the objective and moving straight to deflation. A lot of lip service—but perhaps not enough credence—is given to the notion of policy lags. What the Fed implements today affects the economy months or years later. The retreat in inflation seen since June of last year has little to do with Fed policy, in our view. The reaction to what the Fed has done or is going to do is yet to come.

For three years, we have stressed that post-pandemic economic developments should not be considered a business cycle. Our perspective is of an economy normalizing around a barrage of unprecedented shocks, beginning with the lockdowns and the bust. Next came the reopening and mega-stimulus. And lastly, the sudden and plunging reversal in monetary conditions. We wondered if all this unprecedented churn of excess savings, liquidity, and rising income growth as employment normalized would allow enough time for inflation to retreat and U.S. monetary policy to pull back. The worst-case scenario would be a shallow recession or below-trend growth—the economic profile more a case of sector-by-sector adjustment from the post-pandemic churn with some industries retreating and others expanding.

So far, that is what has been playing out. Falling energy prices and improved supply chains are positives for growth, which offset some of the negatives. Personal income and spending growth offer the best perspective on the enormous distortions; after three years, these two measures have realigned but with a very low savings rate.

What is not normalizing and what makes the Fed’s job even harder is fiscal policy. Based on my calculations using U.S. Treasury data, government spending was US$6.6 trillion and rising for the 12 months ending May of this year, over US$2 trillion more than in December of 2019 or 46% higher and roughly US$1.2 trillion above the pre-pandemic trajectory. Despite the strength in the economy and the low level of unemployment, government spending relative to gross domestic product (GDP) is running at a pace more comparable to levels seen during recessions.

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) board members do not think they are done, maybe because they are fighting with fiscal policy. More things will break if the Fed follows through, and we are right in our inflation outlook. The first sign of systemic stress emerged last year in the UK pension industry. The second shoe to drop was this year’s regional bank failures in the U.S. and ongoing disintermediation. The Fed’s position means another shockwave is likely to hit before the central bank begins to ease up.

A de-coupled world

The diverse conditions outside of the U.S. do not change the story to any major degree. The Fed wants things to slow; China’s leaders want things to pick up; the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) monetary vice already has the economy in a technical recession, but it must do more because of stubbornly higher inflation; and in select emerging countries policy is even more stringent than in the U.S., judging by yield curves. This divergence explains why global growth is uneven and argues for much reduced inflation.

China’s reopening has fizzled due to feeble domestic consumption. Nothing could be more crystal clear about the state of domestic demand in China than its inflation data. According to the latest data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics, core CPI is close to zero, producer prices are falling, and China is exporting its deflation to the rest of the world.

Efforts to reflate the system with public policy are compromised by a number of factors. China’s augmented budget deficit is probably already over 10%, based off an April 2022 report by the Institute of International Finance. The authorities do not want to boost leverage, nor do they want to fire up property speculation. However, the priorities of President Xi Jinping are the biggest impediments to rebooting China. Under his leadership, anti-corruption, national security, oversight of private companies, property speculation, and the stability of the Chinese Communist Party have taken priority over economic growth. President Xi did a U-turn on COVID containment late last year and elevated growth as a priority in the wake of public protests. But the follow-through has been tepid.

ECB rate hikes have already led to a technical recession, but it seems likely to worsen because of the economic zone’s stubbornly high inflation rate. Europe’s monetary profile is horrible, in my view; banks are not lending—annual growth in lending to both households and businesses dropped close to zero in April, according to the ECB. Bank lending is much more important in Europe than the U.S. and accounts for the majority of financial intermediation. The poor lending data rhymes with the June production manager surveys, showing a generalized contraction in European manufacturing. Meanwhile, the non-manufacturing survey is barely holding above 50. One reason for the stubborn nature of inflation is fiscal policy. Roughly 800 billion euros in fiscal support have been provided to EU business and households to help offset energy costs.

Strategy

We are bullish bonds, which is expressed across portfolios through investments in Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) bonds, and select emerging market bonds.

The biggest pricing anomaly in the fixed income markets is the U.S. yield curve, more extremely negative than at any time in modern history except for the early 1980s. Yield curves in some emerging countries are even more inverted. We believe the risk/reward profile warrants long duration positioning. Everything mentioned earlier points to a bull steepener in the yield curve. A Fed-provoked recession could trigger a bond rally; our base case of falling inflation and a mild economic downturn would also support the bond market but with less upside.

There is some near-term risk to the upside in yields if the Fed continues to raise rates and nominal GDP growth remains strong a while longer. However, history shows GDP itself is a poor early warning indicator of a sudden drop-off in activity, the data generally remaining firm right up to the moment it weakens.

On the currency front, the U.S. dollar is overvalued based on most metrics but not in the extreme. In addition, tight monetary policy and expansionary fiscal policy is typically constructive for a currency, which is the current policy backdrop in the U.S. Consequently, our foreign currency allocations out of dollars are on a selective bilateral case-by-case basis.

Francis A. Scotland is a Director of Global Macro Research at Brandywine Global, an independent affiliate of Franklin Templeton. Franklin Templeton is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment or financial product advice. It does not consider the individual circumstances, objectives, financial situation, or needs of any individual. The information provided should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. It should not be assumed that any of the security transactions discussed here were, or will prove to be, profitable.

For more articles and papers from Franklin Templeton and specialist investment managers, please click here.