The question around active versus passive managers is subtly but critically predicated on the lazy assumption that it is not possible to consistently choose managers that outperform. By extrapolation, if you cannot choose managers that consistently outperform, then you should settle on passive managers which at least won’t extort as much for the privilege of making less than the benchmark.

But both the premise and (hence) the narrative are flawed.

Re-cap passive versus active

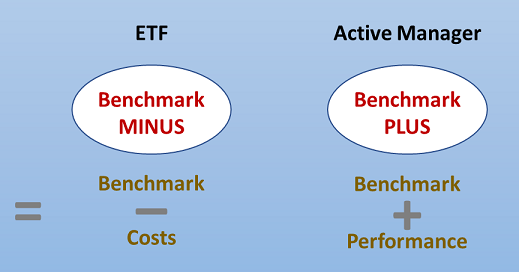

A passive investment such as an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) is a reasonable starting point to commence the investing journey. It generally charges low fees, is professionally administered, and employs a strong level of corporate governance and oversight. ETFs can also provide a good way to gain exposure to offshore companies and specific thematics.

For these reasons, passive investments provide a good starting point for retail, inexperienced and non-professional investors.

But there are some limitations. To begin with, ETFs cannot replicate an accumulation index to achieve proper compounding as there are too many moving parts. An ETF still charges management and administration fees. And most importantly, an ETF aims to perform in line with an index – not out-perform the index. And it is this last point which is most critical in the context of long-term wealth accumulation.

Re-cap on compounding

If you have followed Katana for a while, you will know of our obsession with investor education, data and the power of compounding. To re-cap a simple but particularly pertinent example, consider the effect of time on long term equity returns.

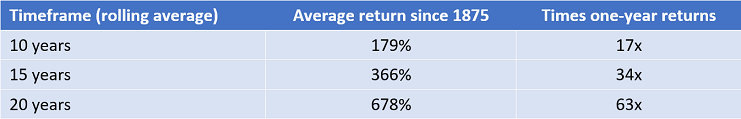

Over the past 146 years, the ASX has averaged 10.8% per annum when aggregating dividends and capital growth[1]. If an investor was to reinvest and compound their earnings each year, these returns would be magnified. And this increase accelerates with every passing year.

For example, after 10 years of compounding, the returns would be equal to 17 years. If the investor was to compound for an extra 5 years, it would double this to be the equivalent of 34 single-year returns. And adding just another 5 years, would double it again, such that compounding for 20 years would produce the equivalent of 63 one-year returns. This accelerates even further with time.

Source: Katana Asset Management

Why active returns are critical

As impressive as this is, let’s now consider the impact that a good active manager can have through time and compounding. By way of example, we have assumed that an active manager has out-performed by 2.7% per annum net of all fees (Katana has out-performed by ~3% per annum net of all fees for 17 years; please note past performance is no guarantee of future performance).

The extra 2.7% per annum when compounded over time produces extraordinary returns. After 10 years, the active management returns would be the equivalent of 24 years versus 17 years for the index. Over 15 years this would have grown to 53 years equivalent one-year returns versus 34 years for the index. And rather incredulously, if an investor was able to achieve an extra 2.7% per annum for 20 years, this would equate to the equivalent of 107 one-year returns versus 63 one-year returns for the index.

Source: Katana Asset Management

[1] Note past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Dividends have averaged 4.54% per annum since Accumulation Index commenced in 1979; assumed at 4.5% per annum prior to that.

This cannot be ignored.

Good active managers do exist and can out-perform over the medium and longer term. And good active managers do have consistent characteristics that can be identified and assessed. This is not to say it is easy, but it is possible. And ultimately that is what investors are paying advisers and consultants for. To generate performance that they could not otherwise generate themselves through passive strategies.

Over the past decade, better investor education and greater transparency of data has led much of the professional advice industry to think that it is too hard to deliver meaningful outperformance. There has almost been a quasi-resignation that it is too hard to generate sustained alpha, so therefore let’s change the narrative to cost-conscious, passive investing.

But the returns above highlight why advisers are selling short those who rely on them. Morally and financially, advisers owe it to investors to get better. Not to settle for less.

Conclusion

The discussion of active versus passive really amounts to the competence and capacity of advisers, asset consultants and investors to select consistently good managers. The question should really be ‘How do we select consistently good managers’ not ‘is active or passive better’? The impact that genuine and consistent out-performance has over time is too compelling to contemplate anything else for professional investors.

Romano Sala Tenna is Portfolio Manager at Katana Asset Management. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual. Any person considering acting on information in this article should take financial advice.