(This article was updated on 28 January 2020 to reflect developments subsequent to the original publication. Other articles on this subject are published here and here).

A record amount of over $4 billion was invested in new Listed Investment Trusts (LITs) and Listed Investment Companies (LICs) during 2019, up from $3.3 billion the previous year. Fixed interest LITs were one of the success stories of the year, with $2.2 billion raised in four issues.

The overall sector now holds $52 billion across 114 issues, and while the fixed income LITs are trading close to the value of their Net Tangible Assets (NTAs) value, most equity LICs are struggling at price discounts to NTA.

But suddenly, there is also a cloud hanging over all new issuance, with financial advisers and stockbrokers unsure whether they can accept selling fees under the Financial Planners and Advisers Code of Ethics 2019 Guidance (it is a guide, not legislature). Amid the uncertainty, well-known global managers such as PIMCO, Neuberger Berman and Guggenheim are hoping to issue in early 2020.

Will advisers participate? Prominent columnist and fund manager, Christopher Joye, opened his Australian Financial Review article on 13 December 2019 in no uncertain terms:

“From January 1 commissions on listed investment companies and trusts will be banned, opening the way to huge compensation claims for losses incurred by any clients other than sophisticated institutional investors.”

The Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority (FASEA) has advised me that Chris Joye's interpretation is incorrect, and this article will explain why. However, a high level of confusion over the proposed Code remains.

Are financial advisers caught in another trap?

In the worst position of all, financial advisers are unsure whether they will breach their Code of Ethics from 1 January 2020. The selling fee for placing clients into new LITs was one of their few bright spots in a tough 2019. The uncertainty arises just when it seemed there was little more that could be thrown at advisers already reeling from:

- the Royal Commission identifying conflicts of interest and not acting in the best interests of clients

- a mountain of compliance and paperwork at every client interaction

- the early removal of grandfathered commissions

- the exit of the major banks which were once big supporters, and

- new education standards pushing thousands out of the profession.

FASEA has produced detailed obligations “that go above the requirements in the law”. It includes five values and 12 standards, and they are imposed on financial advisers personally:

“You have a fundamental, personal, professional obligation to understand and to adhere to your ethical obligations under the Code. You cannot outsource this responsibility … You will need to keep appropriate records to demonstrate, if called upon, your compliance with your obligations under the Code.”

With responsibilities that are almost impossible to quantify and judge, the five values are Trustworthiness, Competence, Honesty, Fairness and Diligence, followed by pages of definitions. Advisers will not be able to pick up the phone to a client without worrying if they have met all potential requirements. The concern is that costs are rising so much that financial advice will increasingly become the domain of the wealthy.

Where do LICs and LITs come into it?

The impact of FoFA on funds and listed vehicles

The Future of Financial Advice (FoFA) regulations prohibit payments from product manufacturers to financial advisers. However, in 2014, the Coalition granted an exemption from FoFA for financial advisers and brokers to continue to receive commissions in the form of ‘stamping fees’. Under Corporations Regulations 7.7A.12B:

“A monetary benefit is not conflicted remuneration if it is a stamping fee given to facilitate an approved capital raising.”

And an 'approved capital raising' includes:

“interests in a managed investment scheme that are, or are proposed to be, quoted on a prescribed financial market.”

In addition, on 27 January 2020, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg issued a media release:

"The Morrison Government is today announcing that Treasury will undertake a four week targeted public consultation process on the merits of the current stamping fee exemption in relation to listed investment entities.

Stamping fees are an upfront one-off commission paid to financial services licensees for their role in capital raisings associated with the initial public offerings of shares.

Public consultation will allow the Government to make an informed decision on whether to retain, remove or modify the stamping fee exemption in order to ensure that the interests of investors are protected and capital markets remain efficient and globally competitive."

Does the Code apply to both financial advisers and brokers?

At first glance, as the Code Guidance addresses ‘Financial Planners and Advisers’, it looks like another attack only on financial advisers. At the Royal Commission, the stockbroking industry barely rated a mention while advisers were hammered.

But the examples in the Code Guidance, discussed below, also apply to stockbrokers and every other Australian Financial Services (AFS) licensee. I checked this point with FASEA, who replied:

“The Code of Ethics is a compulsory Code for all relevant providers (as defined in the Corporations Act) when providing personal financial advice or services to retail clients on relevant financial products. Stockbrokers fall within the definition of a relevant provider and therefore must comply with the Code when providing personal financial advice or services to retail clients on relevant financial products.”

Brokers have become major supporters of LICs and LITs in recent years as they receive fees similar to the rewards of floating a new company. When a new LIT or LIC comes to market, the issuer (manager) selects a syndicate of brokers with the ability to market and sell this type of transaction. A welcome development in recent deals is that the managers cover the up-front costs, enhancing the potential for the issue to trade around its issue price. The manager pays a selling fee, as noted in the recent KKR offer (the largest of 2019 raising $925 million) document:

“the Manager will pay to each Broker a selling fee of 1.25% (exclusive of GST) of the amount equal to the total number of Units for which the relevant Broker procured valid Applications.”

KKR also states that:

“The Responsible Entity does not intend to pay commissions to financial advisers in relation to an investor’s investment in the Trust under this Offer.”

There is nothing to stop brokers paying fees to financial advisers who place their clients into the funds. In some cases, the commission may be refunded to the clients. In the case of KKR, half the transaction was placed by brokers and half by financial advisers, with the adviser receiving most of the selling fee from the broker.

What does the Code of Ethics say about fees and commissions?

The FASEA Code of Ethics Guidance addresses ethical issues facing financial advisers, and is also relevant to investors want to know what happens to the selling fee.

Christopher Joye sees FASEA’s position as clear:

“In one of the biggest shake-ups of the financial advice industry in years, the government’s Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority has blanket-banned conflicted sales commissions, including previously acceptable “stamping fees”, for advisers recommending listed investment funds to both retail and wholesale clients ... The ban on stamping fees for LICs and LITs for all advisers is therefore black and white (my bolding).

Joye quotes from Examples 6 and 9 of Standard 3, including from page 17:

“The option to keep the stamping fee creates a conflict between [the adviser's] interest in receiving the fee and his client’s interests. Standard 3 requires [the adviser] to avoid the conflict of interest. It is not sufficient for him to decline the benefit as it may be retained by his principal. Either the firm must decline the stamping fee altogether, or [the adviser] must rebate it in full to his clients.”

Joye says there’s “no room for confusion” there. In fact, there is plenty.

There’s no outright ban on ‘stamping fees’ to advisers

Example 6 concerns a stockbroker, Yasmin, who is motivated to do the transaction because she needs the extra brokerage income to meet her monthly target and earn a bonus. FASEA says:

“the actual reason for advising the clients was to earn an increased proportion of total brokerage by ‘churning’ client accounts.”

The Code does not say she cannot accept the commission (stamping fee), it says it cannot be her primary reason for the deal. In fact, FASEA says the usual practice is:

“Her firm takes advantage of the carve out from the conflicted remuneration provisions introduced by the Future of Financial Advice reforms”.

Example 9 is the same. This is headed, ‘Selling IPOs’. It starts: Scott works for a securities dealer which specialises in advising in small cap stocks.” Again, it’s not a financial adviser, it’s a broker. Scott’s firm allows its advisers to either keep the stamping fee or rebate it to the client. However, on this occasion, Scott keeps the stamping fee to pay for school fees whereas he usually rebates to the client. This is how the conflict of interest arises, as it is a change of behaviour. It’s not that keeping the stamping fee is prohibited.

From 1 January, investors who pay an annual fee to their adviser should ask what happened to the stamping fee on new LIT and LIC transactions as a check on potential conflicts of interest.

The Code of Ethics offers flexibility

Outside of these examples, on page 17, FASEA allows financial advisers to receive “Income derived from ancillary products and services”. It says:

“You will not breach Standard 3 if you share in profits generated by the provision of ancillary products and services to clients providing that:

- the ancillary products and services are merely incidental to the adviser’s dominant purpose in providing advice, and

- the ancillary products and services recommended are in the best interests of your client – conferring on the client value that is equal to or greater than that offered by any other option.”

The reason Examples 6 and 9 breach the Code is because of the change in behaviour, such that:

“You will breach Standard 3 where the dominant purpose of providing advice to clients is to derive profits from selling those clients ancillary products or services from which you personally benefit.”

As a further nod to flexibility, page 6 of the Code says to financial advisers:

“Individual circumstances will differ in practice and, as with every profession, there is allowance for differences of professional opinion on how the ethical rules of the profession should apply in a particular case. Doing what is right will depend on the particular circumstances and requires you to exercise your professional judgement in the best interests of each of your clients.”

The Listed Investment Company and Trusts Association (LICAT) argues in a recent release:

“We note, however, that there are significant gaps and differences between the explanatory wording provided in FASEA’s Code of Ethics Guidance and ASIC’s Regulatory Guide RG 246.

The first significant difference is how conflicts of interest can be avoided in practice while continuing to ensure that investors receive the best possible advice. ASIC’s Guidance recognises that there are practical ways in which conflicts may be eliminated including a client authorising a fee to be paid to their adviser for services that have been provided. At this time, FASEA’s Guidance has not explicitly addressed this important point.”

What would a disinterested person, in possession of the facts, conclude?

At this point, it seems fine for both brokers and financial advisers to accept a selling fee from a fund manager, but what about conflicted remuneration and best interests?

Is there a difference between a fund manager with an unlisted fund paying commissions to an adviser (banned under FoFA), and a fund manager listing a fund and paying a selling fee to a broker, who then shares it with an adviser?

FASEA says there are overarching principles which should dominate decision-making by advisers and licensees, such as on page 17:

“You will breach Standard 3 if a disinterested person, in possession of all the facts, might reasonably conclude that the form of variable income (e.g. brokerage fees, asset based fees or commissions) could induce an adviser to act in a manner inconsistent with the best interests of the client or the other provisions of the Code.”

We cannot avoid the elephant in the room. How does a relatively unknown fund manager raise nearly a billion dollars in a month when there are plenty of similar managed funds readily available? For example, there are dozens of fixed interest funds on the ASX's mFund service offered by leading global managers (Janus Henderson, Legg Mason, Aberdeen, PIMCO, UBS) which struggle for attention, and there are many fixed income ETFs which are cheaper than LITs.

Have financial advisers and brokers really considered whether these are better for their clients than a new LIT which happens to pay a 1.25% selling fee (and in some cases, invests in non-investment grade securities)?

Consider this: PIMCO has long offered the ‘PIMCO Australian Focus Fund’, a fixed interest fund holding asset types that LIT investors have scrambled into in 2019. Let’s say they offer it in four formats:

- A managed fund on various platforms. Commissions are banned under FoFA.

- A managed fund accessed using the ASX mFund service. Again, commissions are banned under FoFA. This fund has raised less than $1 million over the years of its availability on the mFund service.

- An active ETF listed on the ASX, with no selling fees (ETFs do not pay selling fees).

- A new LIT with a selling fee of 1.25%.

It’s the same fund from the same manager with the same strategy, and three of the vehicles can be accessed directly on the ASX. Money would trickle into the first three, but it would flood into the fourth. On the LIT, the brokers would hit the phones to their own clients and financial advisers and generate large inflows for a 'global fund manager specialising in fixed interest securities'.

Can anyone deny that many brokers and advisers are motivated by the selling fee? Some of the advisers rebate the fee but what about the rest? Was a LIT offered in a particular month the best fixed interest fund available, and so much so, it deserved a billion dollars? That’s a stretch.

On FASEA’s test: What would a disinterested person, in possession of all the facts, reasonably conclude?

When I asked a financial adviser how he can justify taking a fee for placing a client into a LIT when he can't on a managed fund, he said it was to offset his risk that the client does not proceed. What about KYC, or Know Your Client?

We will never know how much of the billions placed into fixed interest is motivated by selling fees to brokers and advisers struggling with the loss of commissions elsewhere, and whether they have explained the risks to their most conservative clients.

Wait a minute. Didn’t Magellan recently raise $860 million on a LIT that paid no commissions? Yes, but Magellan is a unique case, having spent a decade developing its own distribution channels and gathering the direct contact details of 200,000 investors.

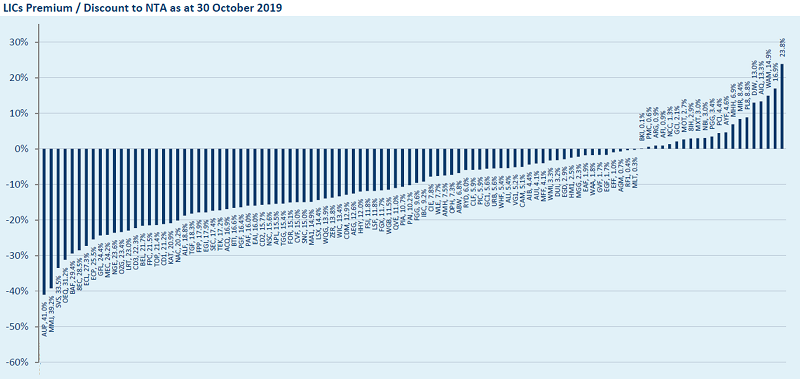

Furthermore, as Joye points out, it’s not as if most LIC investors have had a wonderful experience. The chart below provided by the ASX shows the majority of LICs are trading at a significant discount to their NTA. While most of the recent LITs have done well (except KKR which has been at a discount to its $2.50 issue price since launch, and as low as $2.41), over 70% of these closed-end funds listed on the ASX are trading at a discount to their NTA value. When a client cannot exit an investment at the market value, there is something wrong with an adviser recommending the product.

What about fees on other listed products?

There’s another elephant in the room. Supporters of LICs and LITs point out that there is no loophole because these products are treated the same way as the initial offerings of structures such as hybrids and real estate trusts (A-REITs) on stamping fees. For example, the recent CBA hybrid paid a 0.75% selling fee. Did the advisers check the dozens of other hybrids for better value?

LICAT argues:

“ASIC’s Guidance (but not FASEA’s Guidance) recognises the practical differences in the capital raising process for coordinated blocks such as listed entities which is done at a single point in time and that of the continuous raising of capital for other investment products such as managed funds and ETFs.”

These examples simply emphasise the problem. Financial advisers and brokers are accepting payments from product manufacturers to place investments with their clients. Every adviser and licensee will have to judge their motivations and whether their actions are a contravention of the Code of Ethics.

It matters little if it’s legal when it’s not ethical

As at the end of January 2020, the Code of Ethics does not ban financial advisers and brokers from receiving commissions on LITs and LICs, but there's another issue. Consider how advisers receiving grandfathered commissions were treated at the Royal Commission, although these commissions were legal. Commissioner Hayne lambasted advisers for their behaviour in retaining the fees five years after the implementation of FoFA that made them legal.

Similarly, the advice industry has reacted with horror at CBA’s recent decision to demand advisers obtain a signed form from fee-paying clients to give trustees comfort that clients are aware of the fees. This is not a legal requirement but was recommended by Hayne. Fees are already disclosed annually and the client has agreed to the fees in the Statement of Advice. Advisers are calling CBA’s decision ‘virtue signalling’, but that’s what the big players are doing under pressure from regulators and the government.

ASIC Commissioner Danielle Press recently wrote an email to industry participants advising:

“ASIC does not expect advisers or licensees to change remuneration structures to comply with Standards 3 and 7 (of the Code of Ethics) until there is certainty with respect to these standards and how they impact on remuneration. This applies to existing remuneration streams such as asset-based fees and commissions that might be considered in doubt.”

The review announced by Josh Frydenberg is likely to ban financial advisers (but not brokers) from accepting selling fees on new issues by investment trusts. While new LIC and LIT issuance will continue with broker support, it will reduce demand and probably result in smaller transactions.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. FASEA has also released a Preliminary Response to Submissions paper intended to clarify the application of the Code. For the moment, it confirms that financial advisers are allowed to accept selling fees. However, it does not change my opinion that advisers and brokers offered a 1.25% selling fee are incentivised to distribute LICs and LITs to clients which may not be the best available fund at the time.