This is Part 1 of a two-part transcript.

There’s a lot of business model disruption in the world and many companies will be left behind by the changes. There will be winners and losers in the years ahead, but sometimes business model disruption isn’t obvious. There are first-order effects when you have changes to business models, but when new technology develops, it affects other businesses and other industries and it’s often not foreseeable.

Watch for second-order effects

If you look at a photograph of the Easter Parade in New York in the year 1900, it is full of horses and carriages. If you fast forward to 1913, the photograph is full of petrol-powered automobiles. Think about what had to happen, such as rolling out petrol stations. Transportation fundamentally changed in 13 years. In 1908, Henry Ford rolled the first Model-T Ford off the production line which enabled an automobile to be mass-produced at an affordable cost.

Many first-order effects are fairly obvious. If you manufactured buggy whips, you effectively went out of business. If you collected manure in the streets, you went out of business. There were 25 million horses in the United States in 1910 and 3 million in 1960.

The second-order effects aren’t as knowable. The second-order effects are what the automobile enabled to happen. An entirely new industry could move goods around far more efficiently. People could start the urban sprawl and move further away. We developed regional shopping centres due to the automobile.

Consider a simple change in technology, the automated checkout, such as in Woolworths and Coles in Australia. Walmart started rolling out these automated checkouts in around 2010 at scale and the other major retailers started doing the same. The first-order effects were a loss of jobs of the people working the checkouts, and retailers reduced their costs. And if one major competitor does that, other competitors follow, otherwise their cost structure is out of line.

But what of the second-order effects? Chewing gum sales have lost 15% of their volume since the introduction of automated checkouts in the US. The checkouts have disrupted the business model of impulse purchases. People do not drive to the supermarket to buy chewing gum, but when you used to stand in those checkout lines, you would pick up some chewing gum. I think mobile phones have had a bit to do with it too, because you now do other things when you’re standing there.

Our job as fund managers is to try and spot the next Wrigley. In 1999, at the peak of the technology bubble, Warren Buffett was asked by a group of students why he doesn’t invest in technology. He said he could not predict where the internet was going but investing in a business like Wrigley will not be disrupted by technology. And look what’s happened. Wrigley sales had gone up for 50 years, every year, before this change happened.

The pace of change is accelerating

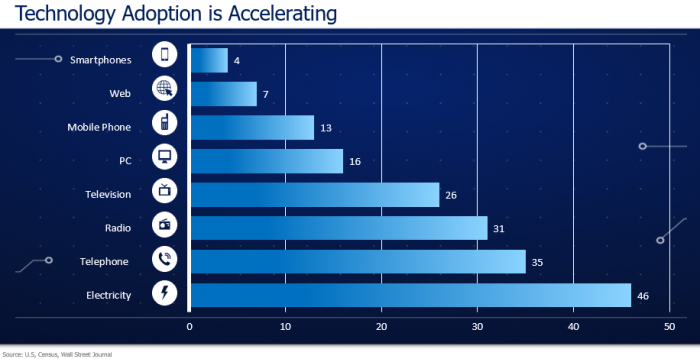

Technology adoption appears to be accelerating. The chart below shows the number of years it takes to reach 50 million new users. We saw the rapid adoption with smart phones, and it only took Facebook five years to move from 1 billion to 2 billion users. These new technology-related businesses can scale at an incredibly fast rate.

I think there’s a whole series of factors explaining why this is happening, and a lot of things are starting to come together.

[Register for our free weekly newsletter and receive our latest ebook, Cuffelinks Showcase]

Register

First, globalisation and the internet have enabled products to spread rapidly to much larger audiences around world. A second factor is the digitalising of goods and services. We have digitalised books, newspapers, music and videos. With Facebook, Google or Netflix, all their services are digital goods. Instead of spreading atoms around the world, we’re now spreading bits around the world where an identical copy of a digital good is produced at zero cost.

Third, the mobile phone today is more powerful than the world’s most powerful super-computer in 1986, in the year I left school, which is absolutely incredible. And now we’re connecting all these devices in ‘cloud computing’, where massive data farms don’t need computers to sit locally, and you can share all this information. So there’s a whole lot of infrastructure and change that’s enabling very rapid change.

The incredible power of two digital platforms

Consider the ‘GAF effect’ from Google, Amazon and Facebook. I don’t mean specifically those companies, but how they are affecting industries and important business models. First is the advertising industry. Google and Facebook know an enormous amount about their users. Anyone who uses Google has something called a Google timeline (unless you’ve opted out of it). On your Google timeline, in your user settings, you can go back five years and it will tell you exactly what you did five years ago if you carried your mobile phone, and most people do.

It tells you what time you left your house, whether you walked to the bus, which bus you boarded, if you went to work or not because it knows the address. If you take any photos on a day, it will put those photos on the timeline. It will tell you where you went for lunch, when you went home and if you went to dinner, it will tell you the restaurant. And this goes for every other day of your life for the last five years. It’s collecting enormous amounts of data about you, as are Facebook and others. That enables these platforms to start highly-targeted advertising and make it incredibly efficient.

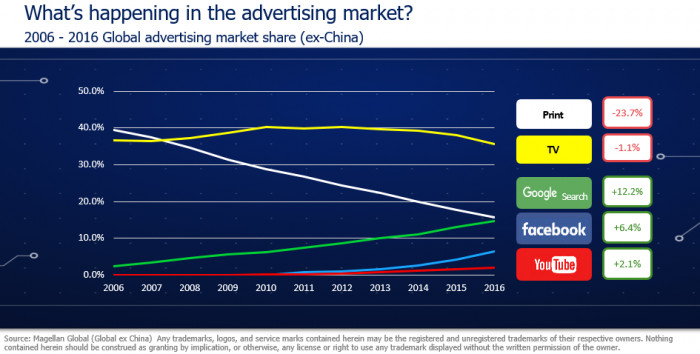

In the last decade, traditional print advertising has lost about 24% market share, and I predict this will go to zero. It is extraordinary that outside China, two companies (Facebook and Google) have taken nearly the entire market share of a global industry that had many, many players in the world – magazine producers, newspapers producers, classifieds producers. All this revenue has ended up with two digital platforms that have this massive network effect. Television advertising, which is the largest pot of advertising money, has not yet been disrupted. We’re starting to see the rise of YouTube but it is still relatively small, as shown below. It’s probably got between US$6-8 billion of revenue at the moment, but it’s an industry with US$150-180 billion of revenue outside China.

Television is next

The television advertising business model is the next to fall due to two big factors. We’re experiencing the rise of these streaming video services. Think of Netflix, Amazon Prime, Stan, and Hulu, and Apple wants to enter this game. These businesses are spending enormous amounts of money on content creation. Amazon and Netflix this year will spend US$10 billion creating original content. They are far outspending anyone else on the planet. Facebook just bid US$600 million for the Indian cricket video streaming rights and were outbid by News Corp’s Fox. I think that’s one of the last-ditch efforts to protect sporting rights and there’s a battle going on between the television and the movie networks. Apple and Netflix are bidding for the next James Bond.

They are taking viewers away from television and pay TV which reduces advertising revenues. Then on the other side, the costs of producing the content and buying the best shows is being bid up. It is not a great business model if your revenues go down and your costs go up.

We’re also seeing the advent of new video advertising platforms. The streaming services are not advertising businesses, they are subscription businesses. But YouTube and now Facebook (and they’ve just launched Facebook Watch) are advertising business models, and I believe that a huge amount of the revenues that are currently in television and pay TV are at risk. It’s fundamentally different, because this is targeted advertising. These platforms know so much about the users that advertisements can be delivered specifically to what the users are watching on these new platforms.

The television advertising model as it currently stands gives a number of companies in the world a huge advantage because there are massive barriers to entry to promote products on television if you want to advertise at scale. It will be much easier to enter one of these new platforms. You can do very specific programmes if you are developing a new brand on Facebook, YouTube or Google compared with advertising on television.

The Amazon effect

Amazon is a business with an estimated US$260 billion in sales (including Whole Foods), the second largest retailing business in the world after Walmart. It’s a fascinating company. They run a ‘first-party’ business, where Amazon buys the goods, stores them in their warehouse and then sells them to their users via the Amazon website or mobile apps. Then they have a ‘third-party’ business called Fulfillment by Amazon, where other retailers put their own inventory into Amazon’s warehouse and then Amazon sells that inventory to their customers as well. So customers suddenly have a much greater selection, and Amazon charges other retailers rent for having their goods in the Amazon warehouse, then charges a commission for selling to the user base.

Amazon also is a massive logistics company. They are expanding warehouse space by about 30% a year and they are incredibly advanced from a technology point of view. They have developed with a robotics company something called the Kiva robot, with about 45,000 of these robots in their warehouses at the moment. Humans are good at putting goods in a package, adding a label and sending them off. But it’s inefficient for the human picker to run around the warehouse to find the shelf where that good is stored in these massive, multiple football field-sized spaces. So these robots automatically go around the warehouse and bring the shelves holding the product to the packers.

The loyalty scheme called Amazon Prime started out with two-day free shipping, then same-day and 2-hour free shipping in a number of cities around the world. Amazon Prime members receive free video, free music and free ebooks with the service.

Amazon is a also a data analytics company. They understand enormous amounts of information about what the customer wants to buy. Amazon members see web pages that look different to anybody else's. There are 50 million goods available in Amazon so customers receive a particular look into the world.

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos wants to fulfil all of his customers’ shopping needs. He worked out that if you want to be in their everyday shopping, you need to be in the grocery shopping habit. They started with Amazon Fresh, an online grocery shopping business that’s very niche. But if you want chilled vegetables or meats or ice cream, it’s inconvenient to have them delivered on the verandah if you’re not there for two hours. A lot of people want to look at their fresh fruit and vegetables and not have anyone else choose that for them. So Bezos bought Whole Foods, the largest fresh food retailer in the US. It had a reputation for expensive produce, lots of organics, incredible displays. On the first day Bezos took control, on the key lines people are interested in, he dropped the prices 35-45%. People shop for incredibly good, fresh groceries then everything else can be put together.

He wants to connect your home by the ‘Internet of Things’. Many goods like washing detergent and milk will have computer chips on them that will connect to the internet to know when you are running out. Washing machines and fridges will automatically generate shopping lists. He’s adopting a voice platform for your house with a digital personal assistant.

What’s next?

There’s a massive number of these revolutions. You may think Amazon and Facebook and Google are big at moment, but we’re in the early stages of where this technology and these businesses are heading. Advertising and retailing is the start. In Part 2, I discuss which large companies will suffer, and bring in the perspectives of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger.

This is an edited version of a presentation by Hamish Douglass, CEO, CIO and Lead Portfolio Manager at Magellan Asset Management, at the Morningstar Individual Investor Conference 2017 on 6 October 2017. Graham Hand attended the event courtesy of Morningstar.