Investors and markets are preoccupied by the US regional banking industry crisis. It is still highly fluid but if history is a guide, investors would be wise to prepare for more tremors. While the recent decision to backstop US bank deposits, the Fed’s newly-announced liquidity facility, as well as UBS’s purchase of Credit Suisse - with massive support from the Swiss regulators and government - are helping to calm skittish investors and depositors, these measures may feed further panic. Moreover, the measures may not avoid a credit crunch as banks withdraw liquidity.

Many investors are concerned SVB and Credit Suisse are the 2023 equivalent of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, the 2008 poster children of the GFC.

However, fears of a repeat are misplaced for several reasons.

First, the GFC was defined by lending to borrowers who could not afford repayments.

Second, US consumers are far less leveraged than they were back in 2007.

Third, systemically important banks are far better capitalised and safeguards have been introduced to avoid a repeat performance of 2008/09.

Meanwhile, analysis of many US regional banks, and in particular their available-for-sale, and their held-to-maturity securities, revealed Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was unique, not only in terms of geographic and industry concentration but also ranking significantly worse than all others in terms of unrealised losses on invested securities. These losses were 100% of equity.

And, as has been widely reported, the unrealised losses it accumulated on its investments represented a disproportionate share of its assets, rendering it particularly vulnerable to a run on its deposits, which occurred amid the drought of private equity and VC funding for its profitless tech company clients.

In a fast-moving financial market environment, it may seem risky to rule out another GFC, but the probability, upon an assessment of the odds, appears to be low.

There are still risks, though

But let's not be mistaken. The movements in bond rates in recent weeks have been extraordinary. As recently as 8 March 2023, the US two-year bond was yielding 5.06%. At the time of writing, less than two weeks later, the same security is yielding 3.86%. That’s a one-quarter reduction in less than 10 trading days. It is the largest drop in yields since the pandemic first took hold.

That move has been driven by the belief the US Federal Reserve’s hawkish stance on the pace of rate rises and the terminal level of rates, will need to be reined-in amid a tightening of credit conditions by the banks. The risk of tightening credit conditions is real.

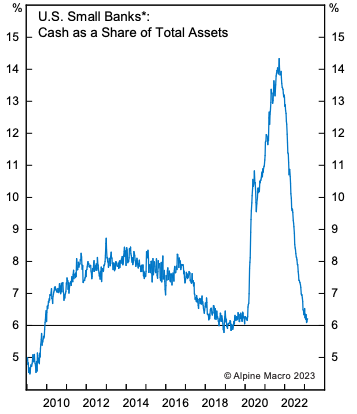

Figure 1. Shrinking Cash at U.S Regional Banks

Source: Alpine Macro, US Fed.

Regional banks, defined as US domestic banks outside the top 25 by assets, have relatively little cash on their books, having invested much of it in longer-duration securities to help drive better returns for their shareholders. The risk is that a run on deposits - over 80% of regional banks’ total assets are funded by deposits - will force more banks to realise an unknown quantum of losses on those long-duration investments. And keep in mind that banks with less than US$250 billion of assets are not required to mark-to-market their assets, which is why the losses are unknown.

QE may have already started

The last time we went through a scenario reminiscent of the current mire, was the GFC, and the global central bank response was Quantitative Easing (QE). That response ignited asset markets around the globe, so it's worth investigating what central banks are up to now.

UK-based economic research house Crossborder Capital (CC) has conducted some useful research into the global liquidity in the last week and it does look like QE is again underway.

For a picture of US dollar liquidity, CC combine the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and foreign central banks’ dollar holdings. They note that as US policymakers acted with "impressive speed” to address the problems of SVB and other US banks, the Fed balance sheet alone jumped by some US$300 billion.

While it looks eerily like the initial actions taken to stem the GFC fallout in 2007 and 2008, the recent measures taken by central banks and sovereign governments include the special liquidity facilities, advancing international swap lines, and record borrowing by US banks from the Fed's discount window.

The latter resulting BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program) effectively promises US-based banks the ability to borrow for up to 12 months at the one-year bond yield plus 10 basis points. (US primary credit – discount window loans - is limited to just 90 days) against the par value of their eligible US Treasury and Agency securities.

This program is the backstop alluded to earlier that supports the balance sheets of those vulnerable regional banks. It simultaneously ensures these banks will generate operating losses on their security holdings because they’ll be borrowing at one-year rates matching or exceeding the yields on their posted collateral.

Some analysts argue the program needs to be made permanent and expanded in terms of its size. As smaller regional banks lose deposits to the major banks, which was anticipated by the regulators and is now occurring, the smaller banks will be forced to borrow from the Bank Term Funding Program. They do this against their eligible security holdings, which currently total US$965 billion.

If the deposit migration from small to large banks accelerates (the regional banks have US$5.5 trillion of deposits), the Fed may have to extend its primary credit/discount window.

If the problem gets worse, more liquidity, an expansion of the US Federal Reserve’s Balance sheet, and QE, are likely results. It seems while we may not enter another GFC, we may soon enter a period where, for equity investors, bad news is good news indeed.

Earnings are what count

As equity markets decline, nothing compromises the immutable arithmetic of PE ratios, earnings growth and investment returns. Even if stocks never become popular again, and their PE ratios, therefore, don’t rise, the annual return will equal the earnings per share growth rate of the companies in a portfolio. So I remain wedded to buying shares in companies capable of generating double-digit earnings growth – and there are plenty of those.

However, the current malaise in markets as discussed above makes stocks delightfully unpopular, meaning their PEs have compressed. So, if I buy shares in companies generating double-digit earnings growth at compressed PE ratios, not only do I receive the earnings growth rate as my return, but I may also receive the bonus of an expanding PE ratio and a stock re-rating. It will pay off when the current tumult passes and stocks again become popular. And that’s the big picture.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.