Don’t panic: This isn’t 2008. In fact, it’s an opportunity to find undervalued stocks unfairly pulled down with bank carnage. Here’s what to do now.

In the US, deposit flight instigated by the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SIVB) and Signature Bank (SBNY) has wrought carnage across regional bank stocks. Investors were shocked by how fast a bank can fail and looked to dump these stocks before a bank run could lead to a complete wipeout. Deposit flight slowed once the FDIC guaranteed all the deposits, not just the insured amount, and just recently the largest U.S. banks committed to deposit $30 billion with First Republic Bank (FRC), one of the most troubled regional banks. However, there could still be a few banks that may not survive. These banks are quickly evaluating their options, including selling themselves to larger banks, raising enough capital to restore depositor confidence, and/or appealing to the regulators for a backstop.

Meanwhile, in Europe, UBS agreed to buy troubled rival Credit Suisse for the lowly sum of 3 billion Swiss Francs. In a surprise twist, the Swiss regulator ordered of Credit Suisse's hybrid bonds while equity holders will still get about 40% of the most recent share price under the deal. Given debt holders are higher up the capital structure than equity holders, the move has uneased debt markets globally.

Here we’ll review what’s different this time around, what to watch for that could make the situation worse, as well as the market and economic impacts.

How is the current situation different from the 2008 global financial crisis?

Except for the rapidity as to how fast these stock prices have fallen, the current situation is much different from what prompted the 2008 global financial crisis. While there are negative economic and market consequences to this liquidity crunch, it will not result in a wholesale freeze across the financial system. The 2008 banking crisis was driven by the fact that no bank understood the extent of losses on each other’s balance sheets. The managers that oversee credit-counterparty risk on trading desks halted trading with other banks as they feared what known as jump-to-default risk, the risk that the other bank could default over the near term. Commercial paper markets froze, interbank lending stopped, and trading ground to a halt. What is different now is that banks do not have the same size holes in their balance sheets as they did then.

In the run up to the credit crisis, banks took on low-quality mortgages, collateralized debt obligations, and CDO-squared. Once the housing bubble popped, these assets were worth anywhere from zero to pennies on the dollar. In most cases, these losses wiped out the amount of equity capital on banks’ balance sheets. Today, the losses on long-dated bonds in hold-to-maturity accounts is much less. For example, a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond bought at historically low yields in 2021 is still worth more than $0.80 on the dollar.

Banking crisis redux?

While we think the fallout of the bank failures in the U.S. will be manageable, the downfall of Credit Suisse may have much broader implications in Europe. In addition to the economic and market-related damage, more disconcertingly, similar to the 2008 financial crisis, its failure raises the spectre of counterparty risk.

Counterparty risk is the risk that the entity that you enter into a trade or long-term agreement with files bankruptcy and is unable to perform their part of the contract. For example, a refiner and an oil company may enter into a forward agreement where the refiner agrees to purchase a set amount of oil per year at an agreed-upon price over the next five years. A common contract in the financial community is an interest-rate derivatives contract, where a bank may enter into a 10-year swap agreement with a corporation to exchange fixed rates for floating rates. Often, banks trade with one another, and may have a large economic exposure to another bank depending on how the value of these contracts may change in relation to the change in the underlying exposure. If one bank were to fail, then these hedges would become worthless.

At this point, the issues with Credit Suisse have been well recognized for months. From a systemic point of view, according to o Morningstar banking analyst Johann Scholtz, “Given that the profitability and capital concerns of Credit Suisse have been publicly discussed for about two years now, we also think that other banks’ exposure to Credit Suisse should be limited. Most exposures will likely be of short-term nature, mostly overnight, and backed by collateral.”

Implications of bank failures in the U.S.

According to Morningstar equity analyst Eric Compton, for now, it appears that the risk of regional banks being placed into receivership and wiping out the equity value has greatly diminished. The question in the marketplace is, What are these stocks worth now?

The key uncertainty is, it all comes down to deposit movement. No one knows for sure how many deposits will move and from whom. An investor has to accept this uncertainty to invest in banks today.

Why does this matter?

- Funding costs are likely to increase as banks have to raise interest rates on deposits in order to retain/attract new deposits.

- If a bank starts to lose deposits, they will replace that lost funding with more-expensive forms of funding, putting even more pressure on costs.

- If depositors move their money to another bank, they are more likely to move their other fee-oriented banking business.

- Ultimately, if any bank loses too many of its deposits (a run on the bank), it becomes an impaired franchise.

Compton notes that the psychology of the depositor has shifted negatively and this probably has not been completely solved even with the actions of the Fed. However, he notes that there are realistic paths for most of the regional banks we cover to recover, although there are paths where things get more difficult as well.

He sees reasons to believe Silicon Valley and Signature were uniquely vulnerable to the types of bank runs we’ve seen so far, and also sees unique vulnerabilities for First Republic. The other banks under our coverage are much more diversified in their business activities.

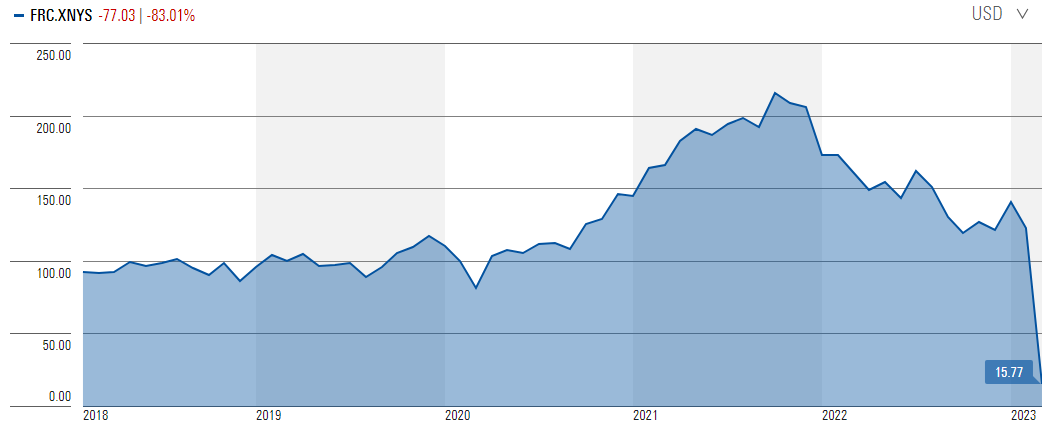

First Republic Bank share price

Source: Morningstar

To account for this heightened uncertainty, we’ve raised the Morningstar Uncertainty Rating on several of our regional banks. While acknowledging that we won’t know more until first-quarter earnings are released, we still think that regional banking will remain an important part of the U.S. financial system.

Economic implications from the bank crisis

From a macroeconomic point of view, the market is grappling with the investment impact if banks pull in lending, and how much could it slow economic growth. Businesses could be pressured by their banks to reduce their borrowing and/or face higher borrowing costs. Other firms may have a difficult time finding new lenders willing to take on new business. We also could see heightened bankruptcy risk as a weaker global economy may result in lower free cash flow available to pay interest costs. Lastly, those borrowers with riskier credit profiles may not be able to roll over debt when it matures. The severity of an economic contraction could also be affected by lower consumer spending if the markets were to sell off more meaningfully.

Equity market implications

Reductions in credit availability and a resulting slowdown in economic growth would lead to a reduction in near-term earnings expectations for the second half of 2023. While we continue to view the U.S. equity markets as broadly undervalued, we note that there could be additional near-term downward price pressure. Cuts to earnings guidance could lead to a combination of risk-off sentiment as well as lowering the P/E multiple they use to value stocks.

In such a downside scenario, lower earnings in the short term do slightly reduce the intrinsic value of a stock; however, the value of a stock is the present value of all the free cash flow it will generate over its lifetime. As such, while present value may decrease slightly, its decline will be limited as cash flows would grow back over time once the economy regains its footing.

What should an investor do now?

First, revisit your appetite to withstand downside risk. Would you be able to sleep at night if we were to revisit October lows? If so, then your current allocations probably don’t need to be revised. If not, then you might want to take a fresh look at your investment needs, strategy, and time horizon.

Dave Sekera, CFA, is a senior U.S. market strategist for Morningstar Research Services LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Morningstar, Inc. Firstlinks is owned by Morningstar. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. This article was originally published by Morningstar and has been edited slightly to suit an Australian audience.

Access data and research on over 40,000 securities through Morningstar Investor, as well as a portfolio manager integrated with Australia’s leading portfolio tracking service, Sharesight. Sign up to a free trial below:

Try Morningstar Investor for free