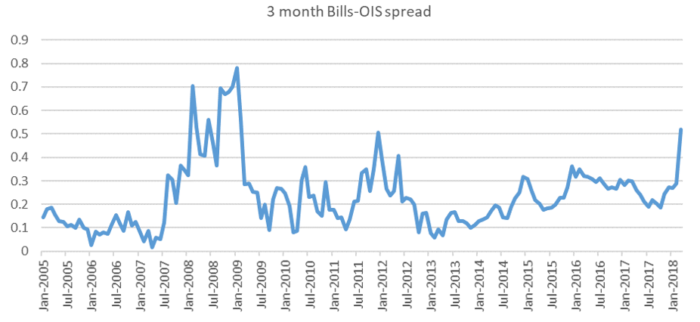

The bank bill rate – Overnight Index Swap (OIS) spread is a keenly watched risk measure in fixed income markets that has experienced a significant widening in recent months, both in Australia and in overseas markets (where LIBOR is the equivalent rate to the Aussie bank bill rate).

The OIS is an interest rate swap whose floating leg is tied to an overnight rate. The OIS market is used in fixed income markets to both hedge exposure to, and speculate on, changes to the overnight RBA cash rate in the future. When market commentators quote statistics like “the market estimates the chance of the RBA raising rates next month is xx%,” they are quoting the pricing of the OIS market.

The bank bill market and LIBOR rates, on the other hand, represent the cost to banks of raising money in the bank bill market for terms generally between three months and one year. As such, the OIS market represents expectations of the short-term risk-free rate, whilst the bank bill rate includes margins for bank credit and liquidity risk.

What is happening here?

In recent weeks, short-term money market rates such as USD LIBOR and AUD bank bill rates have increased sharply and have risen relative to measures of the cash rate. Some market commentators have highlighted this as a risk to market stability.

However, we view the current environment as relating more to an environment of tightening global liquidity and increasing government bond supply. This is having knock-on effects on domestic liquidity.

Source: Bloomberg, Ardea

Causes of widening in LIBOR-OIS

Some of the more commonly cited influences pushing LIBOR rates higher include the potential for USD repatriation flows following recent tax changes, and the significant increase in issuance of US Treasury Bills seen in recent months. However, some other factors have also been at work too.

One additional influence is the potential reallocation of US dollar reserves by China. Given recent tariffs and resulting trade tensions, the desire of the Chinese authorities to diversify their holdings is likely to be high. Reduced demand for US Treasuries from China, and perhaps net reductions, would be consistent with a worsening short-term cash flow position for the US Treasury.

On tighter bank regulation, while much of the heavier burden reflects actions taken by global regulators some time ago, these constraints limit a bank’s ability to hold large inventories of government bonds and corporate bonds. This makes it harder to finance the purchase of government bonds, which in turn has resulted in repo rates widening substantially in recent weeks. Repo rates are a secured funding rate, as the repo rate is the rate earned on lending cash when accepting government bonds as collateral.

This has fed directly into upwards pressure on LIBOR and bank bill rates, as unsecured and secured funding rates in the money market are closely linked.

We would thus add repo rates and perhaps reserve reallocations as additional influences in pushing LIBOR rates wider relative to OIS.

This time, it’s not about credit quality

It’s notable that two of the major factors in wider LIBOR-OIS rates relate specifically to government bonds, and not corporate bonds or banking sector concerns. For this reason, we would describe the current widening as having different underlying fundamental causes from that seen during the GFC.

The reaction seems to mainly relate to liquidity becoming increasingly scarce, and money market rates being priced higher accordingly. This is quite different from the GFC episode, where the blowout in LIBOR rates was directly attributable to a lack of willingness by banks to take overnight exposure against each other.

If credit concerns were rising, we would expect government bonds to be in high demand, and repo rates (i.e. secured rates) to decline amid a flight to quality. This isn’t happening, and in fact we are seeing the opposite with repo rates rising by more than LIBOR rates.

Other evidence that this is not a banking sector crisis is that bank share prices have generally been fine from a top down global macro perspective, setting aside the domestic factors such as the banking sector inquiry and slowing house prices.

Credit Default Swaps (CDS) haven’t moved much either. A CDS provides direct insurance against a default, so if credit were a concern we would see these rates rising rapidly.

The regulatory reforms and protections put in place since the GFC have generally required banks globally to hold much more capital than previously. This places banks on a much stronger footing, but counting against this is the reduced ability to access government bailouts, due to strong reluctance from governments to repeat the bailouts of the GFC.

Broader market impacts of higher funding costs

If the heightened LIBOR-OIS spreads remain persistent, they will create a higher cost of funding for domestic banks. An increase in funding costs will ultimately be passed through to end borrowers. This will affect both households and corporates, in the form of higher mortgage and borrowing rates. If the increase in bill rates were maintained for long enough, this could effectively act in a similar manner to a regular rate hike from the RBA.

Overall, we view the increase in LIBOR-OIS spreads as a result of tightening liquidity globally arising from greater banking sector regulation, and withdrawal of earlier stimulus by the major central banks.

The wake-up call for markets is creating welcome opportunities for price discovery after a period of extremely low volatility. This allows greater scope for active management strategies to deliver additional value through understanding the market dynamics and second-order impacts of situations like this.

Tamar Hamlyn is a Principal of Ardea Investment Management. The information in this article is general and is not intended to constitute advice or a securities recommendation. It does not take into account the investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs of any individual.