The December 2018 quarter reminded investors of the importance of considering risk when constructing portfolios. Questions remain on a possible global growth slowdown and how asset classes will perform. It is an opportune time to revisit portfolios and fortify them against this sobering outlook with government bonds such as highly rated and liquid sovereign bonds, state-based or agency debt (minimum rating AA) or supranational paper (e.g. World Bank issuing in A$).

The investment context

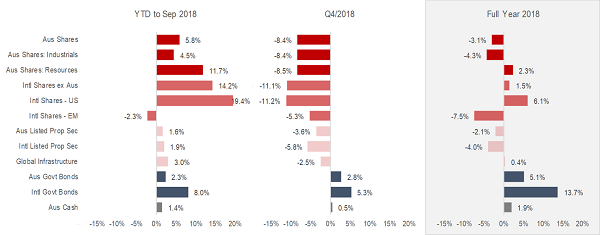

For much of the calendar year to September 2018, adding risk exposures such as shares and property which leveraged easy monetary conditions performed strongly, as shown below. Simultaneously, many questioned the merit of holding high-grade government bonds (‘high grade’) given apparently higher returning or higher yielding credit-based alternatives.

In fact, over 2018, Australian high grade topped the return charts but, more importantly, played their defensive role, cushioning against negative share markets, providing principal and income stability and delivering liquidity.

Total market returns for popular asset classes for 2018

Source: JCB team analysis, Bloomberg to Dec 2018.[i]

Deep in a late-cycle environment, beware credit-based exposures

The world has continued to lurch even deeper into late-cycle, magnifying financial system risks. The easy conditions (record low policy rates, readily available credit, U.S. stimulatory one-off tax cuts and repatriation) are being reversed by tightening monetary policies worldwide. For investors, these changes have profound implications for defensive ‘income’ exposures in an anticipated lower forward-return environment:

- Asset class returns since 2009 have been inflated by the distortional policies. A return to properly-calibrated market risk means returns will likely revert closer to (or lower than) trend partnered with bouts of volatility. In this late-cycle stage, investors should be mindful of being compensated for the risks they are taking.

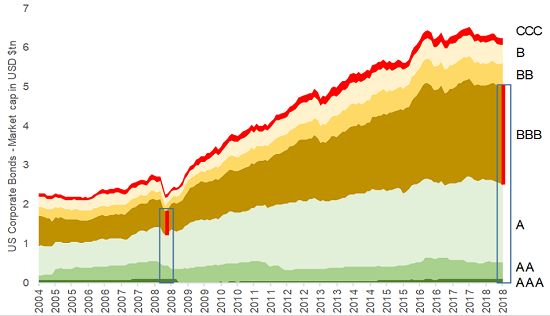

- Corporates have enjoyed a strong run since the GFC driven by low rates and share buybacks. However, the debt levels they have assumed are enormous at ~US$9 trillion (a +64% increase since 2009). Now they face the hurdle of rolling over debt into a hiking rate cycle. According to S&P Global Ratings (August 2018), investment-grade corporate credit will need to refinance about US$600 billion in 2019, ballooning to over $660 billion in 2020 and to $700 billion in 2021.

- With around half of all U.S. investment-grade debt rated BBB (i.e. one notch above junk, see below), we question the quality of these assets and the risk of default. The financial system interconnectedness (such as the sources of wholesale funding needed by the large Australian financial institutions) has global implications.

US corporate bonds market capitalisation by credit rating

Source: JCB team analysis, Bloomberg.

- Credit-based debt is in danger of suffering material and sustained underperformance in a time of tighter lending, less liquidity and ultimately growing corporate defaults. In stressful periods, credit-based exposures have behaved less defensively and more like equities as demonstrated during 2007-2009. The venerable Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, Norges Bank IM, underlined that holding corporate credit amplifies portfolio risk when substantial equity positions are already held. With credit spreads having already tightened in this late-cycle stage, credit-based holdings are not compensating investors for the risks in holding this exposure. This is notable considering the clear dominance of equity holdings in many Australian portfolios.

How do high grade bonds differ from other bonds?

Australian investors are, on average, significantly underweight bonds and, in particular, high grade bonds. Willis Towers Watson’s annual Global Pensions Asset Study in February 2018 reported that bond allocations for Australians are small in absolute terms (14%) and low in contrast to other major developed economies, including US (21%), Canada (31%), Japan (56%), Netherlands (50%), Switzerland (34%), U.K. (35%).

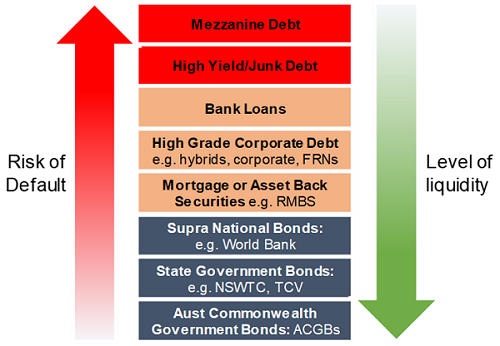

The bond allocations as shown below tend to be dominated by credit (corporate debt, hybrids, floating rate notes) and securitised (asset/mortgage-backed) debt which offer a higher yield but come with lower liquidity in times of stress and risks of default.

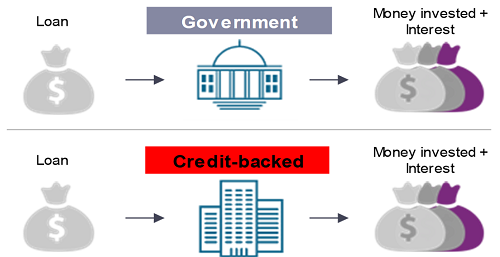

In contrast, high grade bonds are backed by AAA-rated (or at least AA) issuers such as governments (Commonwealth or state/territory) which is reflective of a relatively solid financial position and an outlook that remains strong versus other developed market countries. The willingness and ability to continue to meet their ongoing obligations should not be an issue.

Not all bond instruments are built or perform the same across different market conditions.

The defensive instrument hierarchy

Source: JCB team analysis.

High grade bonds uniquely defend portfolios

High grade bonds can dampen share market volatility in a diversified portfolio by:

1. Providing principal and income stability

The sheer strength of the issuer combines with the macro tools available, such as the ability to raise revenues through taxation, reduce spending and issue more currency. Principal and income stability is generally solid for highly-rated governments, delivering principal and income stability for this asset class. This design means that high grade bonds represent something different other than financial sector risk which is embedded in other assets so common in Australian portfolios.

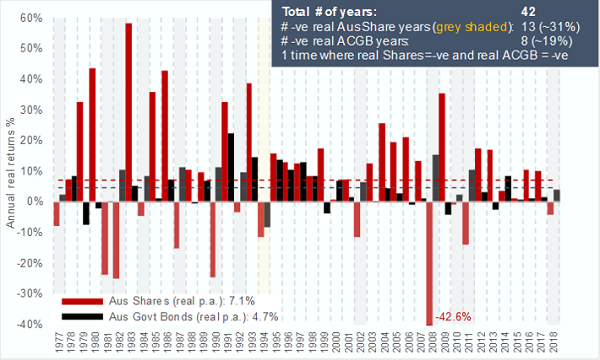

It’s also a key reason why high-grade bonds have historically played an effective role in offsetting weak real (i.e. after inflation has been accounted for) share market performance, as shown below. This has been the case for extended periods, inclusive of varying inflationary and economic periods. Since 1977, there has only been one year where both real returns on shares and Australian Commonwealth Government Bonds (ACGB) have both been negative.

Real returns by year, shares versus government bonds, 1977-2018

Source: JCB team analysis, Bloomberg data.

2. Performing in a rising rate environment over time

Compared to shares, high grade bonds are self-rebalancing and are an asset class that derives the majority of its returns from income, and the income earned on its income. A hiking rate cycle (lower bond prices) leads to maturing bonds and coupons being re-invested at higher rates. Nearer-term returns may be modestly dampened but, over time, holders of this exposure greatly benefit from compounding.

Contrast this to the experience of corporate debt: a rising yield backdrop would increase the stress on the firm as a dramatically-falling bond price would tend to indicate financial woes. To make good on their coupon obligations, the firm would need to grow income (as they do not have access to the same macro tools governments have) while managing financial stress.

3. Delivering portfolio liquidity

The underlying securities attract major offshore investor interest (over 60% of investors in ACGB are from overseas given relatively attractive yields). Term deposits have the investor locked into terms and redeeming early generally results in penalties.

Closing thoughts

Liquidity and asset quality in defensive assets play a key part in effectively mitigating portfolio risk. High grade provide stable principal and income returns and protection against cyclical downturns. They should play a core role in partnership with other defensive assets across the spectrum such as credit and cash.

The challenge is to right-size the allocation so that investors can secure better portfolio control and be clear on sources of return between high grade bond and credit exposures. In the current late-cycle environment where Quantitative Easing is converting to Quantitative Tightening, returns previously enjoyed will become more modest. It is time to shore up defences with high quality and liquid assets.

Paul Chin leads investment research at Jamieson Coote Bonds (JCB) and serves on a number of investment committees including asset allocation and manager selection. This article is for general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.

[i] Notes to return calculations: Aus Shares: S&P/ASX 300; Aus Shares Industrials: S&P/ASX Industrials; Aus Shares Resources: S&P/ASX 300 Resources; Intl Shares ex Aus: MSCI World ex Aus in A$; Intl Shares – US: S&P 500; Intl Shares – EM: MSCI Emerging Markets in A$; Aus Listed Property Securities: S&P/ASX 300 Listed Property Securities Index; Intl Listed Property Securities: FTSE EPRA NAREIT DM; Global Infrastructure: S&P Global Infrastructure; Aus Gov Bonds: Bloomberg Ausbond Treasury Bond Index; Intl Govt Bonds: Bloomberg Barclays G7 Index hedged to USD in A$; Aus Cash: Bloomberg Ausbond Bank Bill Index. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.