On a recent road trip, I was listening to a bunch of Taylor Swift and Andy Williams’ CDs and what struck me was how different the topics of the songs were. Andy’s covers were far more upbeat (with songs like ‘Happy Heart’ and ‘For All We Know’) whereas Taylor has lots of ‘somebody done me wrong’ songs. Of course, it’s dangerous to generalise but then I saw a study from the University of Innsbruck finding that songs have become “gloomier” and “angrier” compared to 50 years ago - which made me think about what it tells us about the wider concept of happiness.

Pursuing happiness is at the centre of our existence. There’s lots of evidence happiness is good for us – happy people live longer, are healthier, more resilient, more creative, are better leaders and are more sociable. Which is where economics comes in. Despite often being portrayed as the ‘dismal science’, economics is in fact all about happiness. The economic problem is about how to maximise utility (or happiness) with limited resources. So, economics can be thought of as the ‘art of happiness’. But measures of happiness have been flat or falling in developed countries. So, what gives? Is economics failing us? This became a big issue in the 2000s with lots of books on happiness. There is now even a regular ‘World Happiness Report’ using Gallup surveys attempting to gauge happiness.

Rampant prosperity

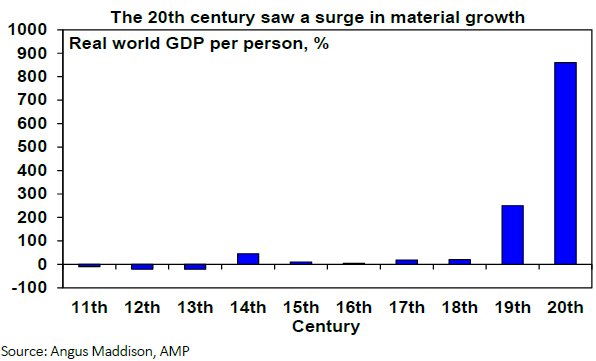

The 19th century saw the start of rapid global economic growth.

This really took off in the 20th century as technological innovations such as electricity, the internal combustion engine and silicon chips came together to rapidly boost productivity. Consequently, real income or Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per person surged globally. This in turn led to a massive rise in material prosperity with, eg: large climate-controlled homes; high speed affordable travel; high quality and variety of food; a huge array of goods; a massive increase in lifespan, and instant communication and entertainment.

But stagnant happiness in recent decades

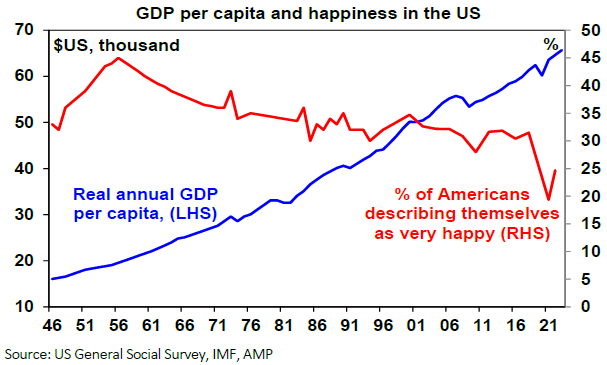

Despite the huge surge in material prosperity there is little evidence that happiness levels in developed countries have improved in the last fifty years. This is illustrated in the chart below for the US which shows the percentage of people who say they are “very happy”, versus real GDP per person. As income has gone up over the last 50 years, happiness has fallen.

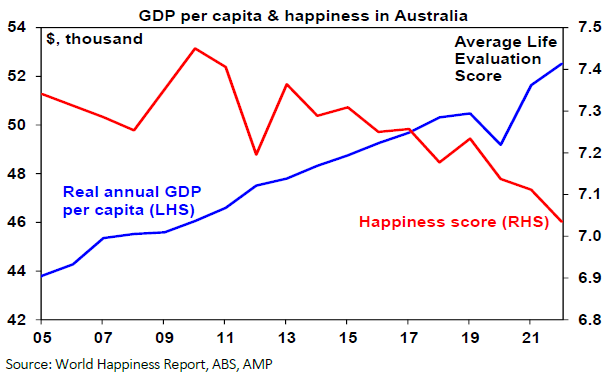

It’s a similar picture for Australia, although we only have Australian happiness data (from the World Happiness Report) for the last 20 years.

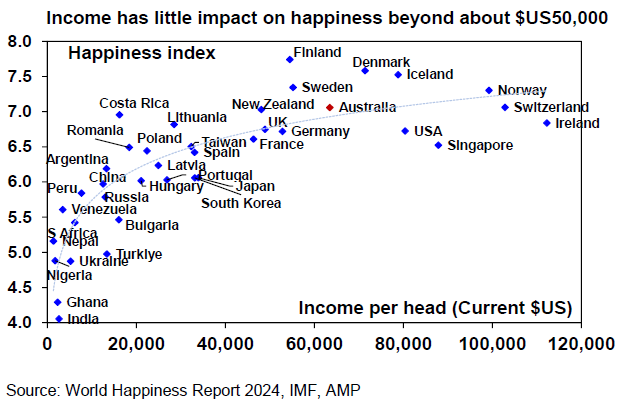

Stagnant or falling happiness is confirmed by rising trends in crime rates, depression diagnoses, suicide rates & drug abuse. This doesn’t mean there is no link between income and happiness. The next chart compares income levels and happiness across countries. At low levels of income, extra income can have a big positive impact on happiness. But for countries beyond a certain level (around $US50,000), extra income has little impact.

This is not to say that happiness is not high in rich countries. In fact, according to the World Happiness Report for 2024 Finland ranks #1 as the happiest and Australia ranks #10 with the US at #23. Lebanon and Afghanistan rank at the bottom at #142 and #143. It’s just that in rich countries variations in income across countries have little impact on happiness. Other findings from the happiness studies are as follows:

- Rich people are happier than poor people. This does not mean that society as a whole becomes happier as aggregate income for everyone rises. This has become known as the Easterlin paradox.

- People compare themselves to others (keeping up with the Joneses) in determining their happiness so if average incomes rise, they may feel no happier, which may explain the Easterlin paradox.

- Women tend to report higher life satisfaction than men, but also experience more negative emotions, suggesting they are less happy.

- Married men are happier than unmarried men, but it’s less clear for women with some studies showing the opposite.

- Younger people in the US, Canada, Australia and NZ are the least happy age group. This is a major change from 20 years ago and may be due to the rise of social media giving rise to increased anxiety and depression amongst the young, particularly young girls. Poor housing affordability may also be impacting.

- Progressives are sadder than conservatives – possibly because they are more empathetic and focused on a more negative world view.

- Physical & outdoor leisure, shopping, reading books, seeing relatives, listening to music and attending sporting and cultural events are associated with higher happiness. Time on the internet and TV is not.

- People in individualistic societies are happier and freedom to make life choices contributes to happiness.

- People adapt to their situation with evidence we are born with a genetically pre-set level of happiness to which we return to after good events (like winning the lottery) and bad (like having an accident).

Some have claimed that most people are on an “hedonic treadmill” of working ever harder to attain material wealth in the belief this will make them happier only to find it doesn’t but resolving to work even harder.

From GDP to Gross National Happiness?

Many argue these findings present a challenge for economists. Economics is about maximising ‘utility’, or happiness. But since happiness is hard to measure, economists assume a good proxy is income and consumption. If consumption is positively correlated with happiness, then policies to boost economic growth will boost happiness. But, if not, this may be misplaced. There are two schools of thought in relation to all of this. The first is to argue economic policy needs to be refocused on broader measures of wellbeing such as Gross National Happiness. The second argues that it is up to the individual to learn how to become happy. The first approach would mean a radical change in economic policy with proposals to boost happiness like these: tax excessive work (as it doesn’t lead to happiness); re-distribute income (because inequality leads to envy and keeps people on the ‘hedonic treadmill’); reduce the focus on competition and rivalry; spend more money on public goods such as parks; refocus on community; limit advertising to information to avoid creating demand for stuff we don’t need; and switch to focusing on Gross National Happiness.

This would have big implications for investors, as these policies would lead to slower profit growth and lower returns from growth assets.

Legislating for happiness makes little sense

However, there are good reasons to be sceptical of proposals for government policy to target happiness:

Firstly, happiness is very hard to measure, making some of the findings referred to above questionable, and impossible to define objectively. Nationally determined concepts of happiness, such as Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness concept, depend critically on subjective judgements that governments (or ethnic or religious majorities) may define to suit them. This can be used to justify religious or ethnic persecution and can be used to advance authoritarian aims.

Secondly, just because we get used to something doesn’t mean we should stop doing it. Rising material wealth may not permanently boost happiness beyond a certain level because we adapt to it. It would have been expected that the huge increase in healthy lifespans or the increase in measured leisure time would have boosted happiness, but it hasn’t. That does not mean we should cut back on health spending or reduce leisure. Policies to increase happiness by cutting work effort or income by redirecting people to other activities may flounder as those activities have the same problems as money, ie, people just get used to them.

Thirdly, while material progress may not be boosting happiness it is doubtful stagnation will either. Curiosity and the desire to advance are fundamental to humanity. Introducing policies to reduce work effort may reduce happiness by suppressing a sense of achievement. Oppression of individual advancement may explain low happiness in socialist countries.

Fourth, restricting choice in favour of officially mandated happiness guidelines may actually reduce happiness as evidence suggests that freedom to make life choices contributes to happiness.

Finally, we are partly dealing here with the outworking of success. The rise in affluence has given people in rich countries the time and money to search for happiness. It should also be recognised that the problems with social media and the decline in happiness it may be contributing to is also a problem of the economic success that gave rise to the technology, wealth and time that facilitate their use. Finding better ways to live with the success that has given rise to social media – a bit like the rules we set around driving cars – is arguably better than threatening to reverse it.

This is not to say that governments should not attempt to measure and boost wider measures of social welfare beyond GDP. But there is a danger in trying to legislate for happiness. There is nothing new in the concept that material wealth won’t lead to lasting happiness. Most religions have long been pointing it out. Buddha long ago observed that most human suffering comes from desire, and this has to brought under control to achieve happiness. But seeking happiness and enlightenment is up to individuals, not the state. Maybe Thomas Jefferson was on to something when he wrote in the US Declaration of Independence that all people had the right to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” with the implication that happiness is something we can only pursue.

Dr Shane Oliver is Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist at AMP. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs.