The Australian superannuation system ensures most people retire with an account-based super pension, either instead of or supplemental to the age pension. A super pension is an attractive investment vehicle because earnings and withdrawals are tax free. People who have saved over their lifetime will hopefully accumulate enough in super to enjoy a reasonable standard of living in retirement.

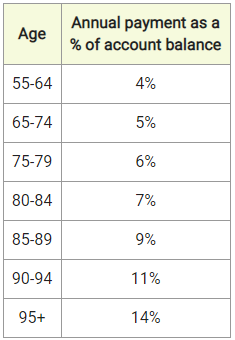

Assuming a person has achieved a so-called ‘Condition of Release’, which generally means achieving the age of 65 (or 60 and ceasing an employment arrangement), they can move super from the accumulation phase of their working years to the pension phase of their retirement. They are then required to withdraw a minimum amount each year, depending on their age, as shown below (source: ASIC’s MoneySmart website).

How much is needed for a comfortable retirement?

The obvious issue is whether taking this much out of a pension account each year means a retiree might run out of money in the account. Of course, superannuation is not the only source of wealth, and usually, people hold savings outside super as well as owning their own home.

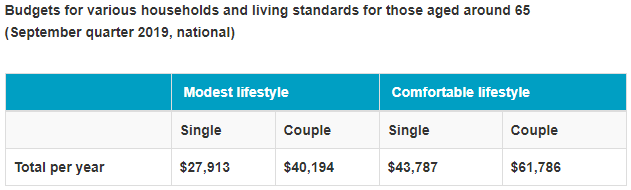

The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) produces an estimate of how much money is needed for both a modest and comfortable lifestyle in retirement. You can see their assumptions here. Crucially, the numbers assume retirees own their own home and are in good health. Home ownership is a massive issue in retirement, and the following amounts will be insufficient for people required to pay rent in major capital cities.

A simple calculation shows the challenge for retirees in the current low rate environment. If a couple has $1 million in two pension accounts earning say 3% per annum, the income is only $30,000 a year. This is far less than the $61,786 a year required for a comfortable lifestyle if their only source of income is the pension account. They will therefore need to draw down their capital to meet expenses. Moreover, the average combined superannuation balance for a couple aged 65 to 69 is about $418,000 (men $247,000, women $171,000).

Consequently, most retirees fear running out of money. Recent research by AllianzRetire+ reveals only 44% of Australian retirees feel secure in their current financial position, and two-thirds spend only on necessities, worried about unexpected costs and illness.

In a previous article, Graeme Colley of SuperConcepts ran the numbers based on the ASFA comfortable standard for a retiring couple aged 57 and 59. There are many variables in calculating how long the money might last, but assuming income earned on the retirement savings is 5% per annum, and the capital is allowed to deplete to zero in the 25th year after retirement, the total amount required in today’s money is $1.1 million.

Withdrawing safely with a better lifestyle

There is no simple answer to the safe withdrawal rate dilemma because it depends on many unknown factors, and there is considerable academic research on the subject. If the account delivers a healthy return of, say, 10%, then drawing down 4% each year is fine. But many highly-conservative retirees are restricting investments to cash which earns less than 2%. This barely covers inflation, and so the capital in the account is depleted each year.

This 4% drawdown level is a common guideline used in the financial planning industry as a safe drawdown rate, but it is based on a desire to spend only the fund’s income and not the capital. This often means the retiree lives frugally and then leaves money in their estate, when they could have enjoyed a better lifestyle.

A group of Australian actuaries has developed a new rule to help retirees who have reached age pension eligibility decide how much they can withdraw from their savings. Their report is called, ‘Spend Your Age, and a Little More, for a Happy Retirement’. Actuaries Institute President, Nicolette Rubinsztein, said:

“The reality is that many people can have a better retirement if they have higher confidence that they are able to draw down a little bit more of their savings than the minimum required by the government.”

“Many retirees draw a bare minimum from their account-based pensions, or their savings, after they stop work. They can’t afford to pay for professional advice from a planner, and they live frugal lives because they fear outliving their savings. But the ‘rule of thumb’ is simple and accurate and takes into consideration a retiree’s asset base and age."

They define ‘optimal’ as a draw down which allows the best possible lifestyle but allows for the fact that spending too much early in retirement means less is available later. The calculations allow for age pension eligibility.

Here is their simple ‘rule of thumb’ for a single retiree:

- Draw down a baseline rate, as a percentage, that is the first digit of their age.

- Add 2% if the account balance is between $250,000 and $500,000.

For example, a single retiree with a super balance of $350,000 could draw down $28,000, which is 8% of $350,000. The draw down amount would increase to 9% when the person reaches 70.

What about people with less money? The actuaries acknowledge that someone with only $40,000 might “buy a caravan and go around Australia”, knowing they can rely on the age pension. But those with more money are more likely to use it wisely for a better retirement.

The main problem with these types of calculations is that hardly anybody knows how long they will live, and life expectancy continues to push out. The age pension is also a safety net for the majority of people. For many couples who own their own house and with other assets less than $394,500, the full age pension including supplements is $1,407 per fortnight, or $36,582 a year. This may be acceptable for a modest lifestyle, but people should aspire to better.

It is, of course, possible to assume a market scenario where someone withdraws only 4% a year and runs out of money, but investing should balance the probabilities. As Michael Kitces, a leading consultant to financial advisers, writes in this article on the old 4% rule:

"The bottom line, though, is simply to recognise that even market scenarios like the tech crash in 2000 or the financial crisis of 2008 are not ones that will likely breach the 4% safe withdrawal rate, but merely examples of bad market declines for which the 4% rule was created."

The lessons behind the numbers

The lessons from these insights, notwithstanding the potential for unlimited assumptions and uncertainty, are:

- The money required in retirement depends on personal lifestyle aspirations, but the conservative 4% rule should not force retirees into living in a state of permanent frugality and thrift.

- Life expectancy and future expenses are uncertain, and anyone who does not want to live on the age pension needs to consider saving more and working longer before they retire.

- Owning a home is a significant risk mitigant (which also comes with the financial advantages of tax-free capital gains and exclusion of the home from the pension assets test).

- Investing wisely and saving early allows the benefits of compound interest to build retirement balances over time. Education on financial opportunities is an important skill.

Retirement years should be a time to enjoy the rewards of a fulfilling working life, not worrying about when the money will run out.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks, published by Morningstar. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any person.