The recent step down in cash rates was a final jolt to the savings of millions of Australians who live on interest from bank deposits. It took term deposits to 2% or less, barely keeping pace with inflation, while many savings accounts now pay negligible interest.

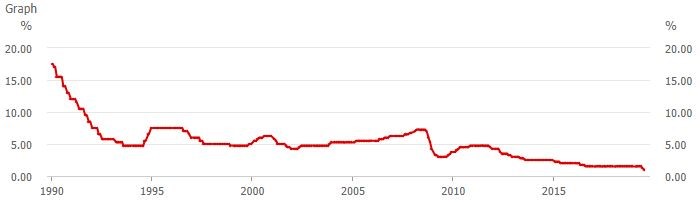

The temptation to invest in bank shares rather than bank deposits to sustain a living standard will be too strong to resist for many. However, it introduces a risk which conservative savers may come to regret as they hanker after the returns of the past, as shown below in the cash rate since 1990.

Source: RBA

Facing up to the TANSTAAFL

People living on income from their savings face an uncomfortable truth. Any investment that is not a short-term bank deposit or government-guaranteed bond carries added risk. The TANSTAAFL, better known as ‘there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch’, is the reality of investing in a low interest rate world.

Over the last decade, the merit of bank deposits has changed dramatically. For example, in December 2009, Westpac offered a 5-year term deposit paying 8%. It attracted $2 billion in a week and Westpac quickly closed it. That term deposit sat in the retirement portfolios of thousands of Australians until 2014, and it’s been a rapid downhill since.

At the time retirees grabbed the Westpac deal, few people would have thought they would never see such a good rate on a bank deposit again in their lifetimes, even if they live until 100 years-of-age. For guaranteed income, it’s more ‘lower forever’ than ‘lower for longer’.

The risk appetite of every person, or acceptance of the reality of TANSTAAFL, varies according to their circumstances. Some older people with good savings capable of financing their later years and perhaps the need to buy into a retirement facility, cannot risk losing their capital. They may need to accept the 2% or less returns.

Other people with more lifetime options can accept some risk for extra return, so let’s survey the income landscape in the listed market on the ASX, excluding investments that carry equity risk. Across Listed Managed Investments, Exchange Traded Products and its mFunds service, the ASX identifies 92 Australian and 38 global fixed income products. It’s a far bigger range than most investors realise.

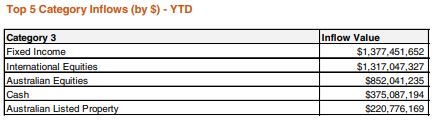

As an indication of how competitive and broad the listed sector has become, Vanguard now has seven fixed income ETFs while BetaShares has five. In fact, in FY2019 as shown below, fixed income ETFs generated larger inflows than any other asset class including Australian equity and global equity. It’s a major change in investing habits and the first year this has ever happened.

Source: BetaShares, year to 30 June 2019

This article focuses entirely on the listed market to demonstrate the choices, but the range of unlisted managed funds is even larger.

1. Cash

The least-risky listed products are ETFs which invest in bank deposits with short duration. The largest is the BetaShares Australian High Interest Cash ETF (ASX:AAA), while UBS issues the UBS IQ Cash ETF (ASX:MONY) with similar assets. Blackrock issues iShares Core Cash ETF (ASX:BILL) which can invest in a wider range of short-term securities. All these ETFs have returned around 2% in the last 12 months, but their returns will fall in line with cash and bank bill rates.

2. Cash-enhanced and floating rate notes

Staying in short-duration investments but adding securities with slightly better returns are the VanEck Vectors Australian Floating Rate Bond ETF (ASX:FLOT), the BetaShares Australian Bank Senior Floating Rate Bond ETF (ASX:QPON) and iShares Enhanced Cash ETF (ASX:ISEC). The extra income comes from buying notes with maturities up to five years, but it comes with a little extra risk because prices of such instruments fluctuate more than cash or bills. Again, returns are likely to follow cash and bill rates.

3. Investment-grade bonds

Now the field really starts to expand as many fund managers offer bond funds which invest in investment-grade credits rated BBB+ or better. With these high ratings, a diversified portfolio should produce acceptable credit risk, and the exposure to interest rates depends on the duration of the bonds. Each fund manager will accept different risks depending on their perception of the opportunities. There are also index funds which have lower fees.

Examples include Vanguard’s Australian Corporate Fixed Interest Index ETF (ASX:VACF) which invests in investment-grade Australian corporate (ie non-government) bonds, while less risky is Vanguard’s Fixed Interest Index ETF (ASX:VAF) because it also includes government bonds. Russell issues its Australian Select Corporate Bond ETF (ASX:RCB) and BetaShares has an Australian Investment Grade Bond ETF (ASX:CRED) and an Australian Government Bond ETF (ASX:AGVT).

These funds usually introduce duration risk which benefits from falling interest rates, and therefore their one-year returns have been impressive as rates have fallen. But here’s where TANSTAAFL kicks in. Future returns depend on the movement of interest rates, and these funds will suffer when rates rise. The decision for the investor, therefore, is not so much credit risk as interest rate risk at this ratings level, although we saw in the GFC how ratings agencies don’t always understand the real risks.

A competitor stock exchange, Chi-X Australia, will join the mix soon with the launch of its own funds market in second half of 2019. It will offer a range of both ETFs and Quoted Managed Funds (QMFs). Around 36% of all Australian ETF trading already takes place on Chi-X so the Funds Market is a logical next step.

4. Higher-yield products

As bonds purchased move down the ratings spectrum, default risk on lower credit quality names starts to become a major TANSTAAFL factor. The benefit of investing with a quality fund manager is their portfolio might include hundreds of issuers with no more than 1% of the exposure to one name, such that a modest number of defaults does not erode capital. However, in a severe economic downturn, the lower credit quality may cause losses. Investors need to weigh the merits of return versus risk.

In the actively-managed ETF space, the BetaShares Legg Mason Australian Bond Fund (ASX:BNDS) carries exposure to government bonds as well as semis, corporate bonds and asset-backed securities, managed by Western Asset.

Moving away from ETFs to Listed Investment Products, the individual fund characteristics vary. Operating in the global market across issuers in many different countries, credit qualities and industries is the Perpetual Credit Income Trust (ASX:PCI), which aims to hold 50 to 100 issues with an overall target return of the RBA cash rate plus 3.25% after fees, over the cycle. The Neuberger Berman Global Corporate Income Trust (ASX:NBI) is even more diversified with 450 global holdings, and it works on a declared annual distribution level, currently 5.25% paid monthly. Vanguard’s most popular global offer is their International Fixed Interest Index ETF (ASX:VIF).

Coming soon, Chi-X will quote its first series of actively-managed fixed income QMFs including ActiveX Kapstream Absolute Return Income (CXA:XKAP) with target return of RBA plus 2-3%, Schroder Absolute Return Income (CXA:PAYS) with target return of RBA plus 2.5% and various eInvest Daintree Capital funds with target returns up to RBA plus 3-4%.

In Australian credits, the Metric Credit Partners MCP Master Income Trust (ASX:MXT) holds a portfolio of directly-originated corporate loans, rather than buying public bonds, with a target return of RBA cash plus 3.25%. Gryphon’s Capital Income Trust (ASX:GCI) invests in asset-backed securities (or securitisations) issued in Australia and targets cash plus 3.5%.

Of course, all these targets are not guaranteed but more like manager aspirations.

At this end of the market, skill and diversification play important roles to manage TANSTAAFL. The reason a manager may deliver 4% or 5% rather than 2% is the added risk dimension.

There are a few ‘notes’ listed on the ASX which don’t receive much attention, are unrated and not highly liquid, but their structure offers good investor protection. They are debt instruments backed by the assets of a larger Listed Investment Company structures. Two examples are NAOS’s ASX:CAMG and Whitefield’s ASX:WHFPB.

5. Hybrids

Hybrids have become a major part of the credit structure of many companies, particularly banks. They mix characteristics of debt and equity but come in a vast array of variations. It is not possible to summarise all the alternative choices here, but they are certainly not all created equally. Many mandatorily converted to equity in certain events, or have their coupon payments suspended.

Margins over the bank bill rate vary according to expected first call date, investor appetite and issuer funding needs, and they are lower in the bank capital structure than senior and subordinated debt, but above shareholder equity. While difficult to generalise, major bank hybrids currently offer up to 3% above the bank bill rate (including franking benefit).

Morningstar has a couple of four-star rated hybrids as at 31 May: Macquarie Group Capital Notes 2 (ASX:MQGPB) carrying a ‘running yield’ including franking credits of 6.44% and Ramsay CARES (ASX:RHCPA), with a running yield of 6%.

For those who prefer not to face the idiosyncrasy of individual issuers or tranches, BetaShares offers the Active Australian Hybrid Fund (ASX:HBRD) with expert selection from the hybrid universe.

6. Other listed products

Two other products are worth mentioning:

mFunds

To improve access to unlisted managed funds, the ASX has an execution service which allows investors to buy and sell managed funds through a participating broker. There are 221 mFunds holding almost $1 billion, of which 19 are Australian fixed income and 29 are global fixed income. Major brands such as Legg Mason, PIMCO, Schroders and AMP are represented.

XTBs

Rather than investing in broad fixed income sectors or funds as with most of the examples in this article, Exchange Traded Bonds or XTBs allow retail investors to choose specific borrowers who have issued bonds in the Australian wholesale market. Buying a bond of a single company removes the benefits of diversification.

Don’t forget the TANSTAAFL feeling

Some of the highest income potential in the listed market comes with an acceptance of risk in other asset classes such as property, shares and infrastructure. Balanced funds provide combinations of assets to match risk appetites.

This is where TANSTAAFL dominates. While a fund might call itself ‘equity income’, it will invest heavily in shares with an income bias, such as the banks and Telstra. There is the tradeoff. A bank might offer a dividend of 8% including franking, but the share price could fall heavily in a market correction, and dividends may suffer in an economic slowdown. This week, we saw AMP suspend its dividend.

Investors in this space must accept TANSTAAFL as the total return from good income may be outweighted by falling capital values.

Also consider investment costs. Placing only $5,000 in a listed product for a 0.5% yield pick up is only $25 a year, which barely covers brokerage and management expenses. It might be better to accept 2% on a term deposit. Take care with some cash-enhanced funds that stray into unusual securities without a reward for the risk.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor, and professional advice should be sought. There are no recommendations in this article. And repeating that the article only focuses on the listed market and there are many unlisted choices.

For more information on the ETFs and LICs mentioned in this article and many more, visit our Education Centre for regular reports. In particular, ETF Reviews are here.