Epidemics and pandemics are an integral part of human history, with each outbreak bearing both social and economic costs. The world has endured a few outbreaks over the past century, and if the early decades of this new century are a reliable indicator, we can expect to see more in the 2020s and beyond.

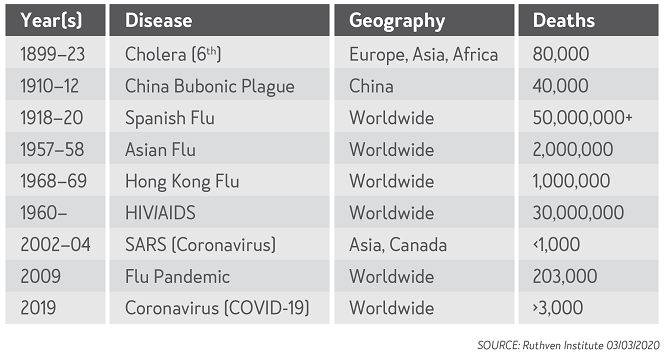

The first table below outlines the main epidemics and pandemics in recent history, when and where they struck, and the resulting death toll.

Impact on coronavirus will prove severe

Of the above list, the two standouts were the Spanish Flu and HIV/AIDS. The first, which occurred in 1918–20, resulted in over 50 million deaths (over 2.5% of the population). The second, which was first observed in 1960s and is still present today, has resulted in 30 million deaths to date (0.6% of the average population until now).

Coronavirus, or COVID-19, originated in China in December 2019 and has since spread rapidly worldwide. The economic impact to global GDPs and stock markets is proving more severe than was anticipated in mid-February, and we are yet to see the full extent of the damage.

The epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, China, has expanded at a record-breaking rate since adopting a state-controlled market economy. Averaging 8.7% GDP growth since 1970, the nation has not seen a recession since Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. However, China’s economy has trended downwards in recent years, as observed in the below chart.

At present, China is also taking an economic hit from swine fever, which is affecting pig production. Now coronavirus is affecting China’s population, trade and general economy to an unknown extent. This setback has in turn affected other economies around the world, including Australia’s export trade of tourism, higher education and minerals.

If the 2002–04 SARS epidemic is any guide, these conditions may only affect economic performance in 2020. However, a looming debt bubble in China may see other problems emerge further into this decade.

Why is the latest pandemic such a worry?

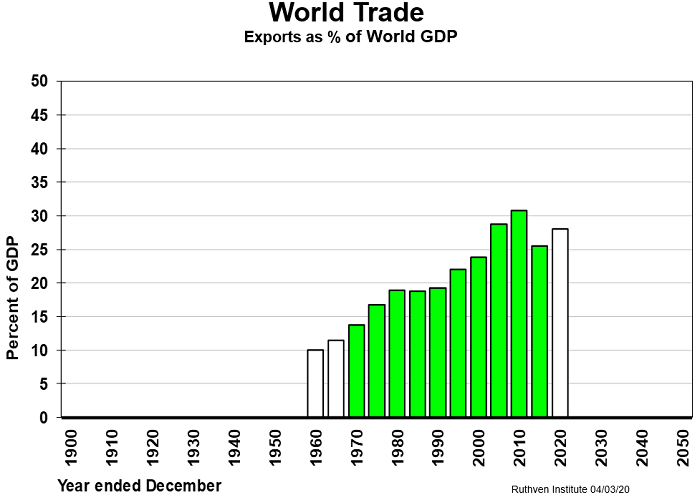

In short, it’s a worry because the world economy now relies upon a lot more international interdependence between economies and businesses. Exports have trebled their percentage share of the world’s GDP from 10% to 30% over the past 70 years, as we see in the next exhibit.

So, the world’s GDP is more vulnerable than ever to any economic downturns resulting from pandemic activity, even if the disease itself is not as virulent on a social scale as, say, the Spanish Flu or AIDS.

A world recession? Doubtful. But a recession in some countries? Quite likely.

Any nation with a growth in 2020 of under 1.5% could be exposed to a recession. If those economies also have high shares of mining, manufacturing, wholesaling, retail and tourism in their industry mix, then they have increased vulnerability due to the high interconnectivity of trade these days.

Australia is vulnerable as a result

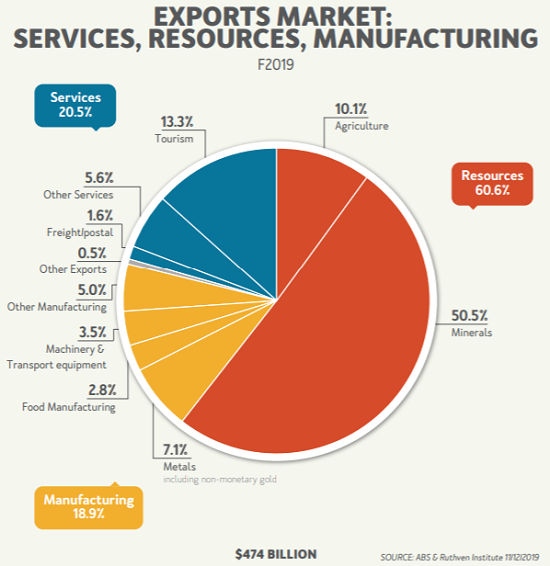

The first chart below shows our export mix (being almost 25% our GDP) with the vulnerable minerals and tourism industries accounting for nearly two-thirds of those exports. These are two of the main industries at risk due to slowing global trade and problems in China.

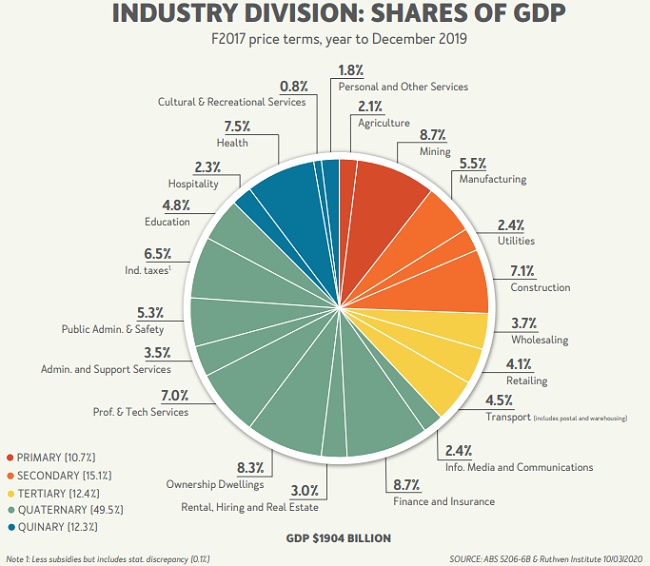

The second chart shows our mix of industries in our $2 trillion economy.

Our small dependence on manufacturing is a big help, but mining is a bigger industry these days.

We may escape a recession but only with a sooner-rather-than-later stabilisation of the viral pandemic and abatement of the fear contagion.

The human impact and equity markets

Of course, the human impact of the coronavirus, separate from the economic impact, cannot be ignored. Shorter quarantine periods, coupled with apparently longer gestation periods than originally thought, have contributed to a faster and greater spread than was anticipated. On the plus side, advances in modern medicine mean vaccines may now become available in record time. But despite a relatively small number of deaths so far, there is no certainty as to how long the pandemic will last.

In times like these, we must consult the experts. It is worth dusting off Peter Curson’s and Brendan McRandle’s 2005 paper, Plague Anatomy: Health Security from Pandemics to Bioterrorism, which addresses the challenge of disease control within the context of national security.

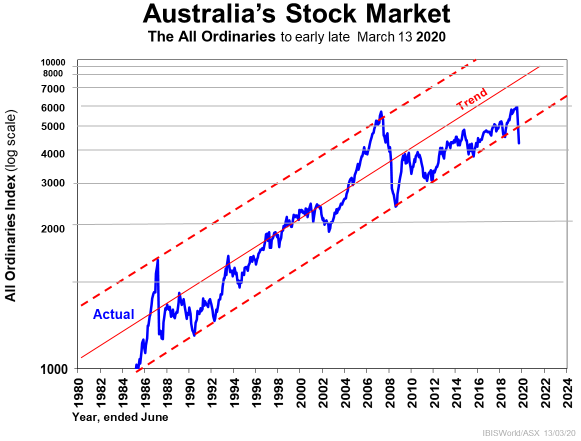

All that said, while stock markets are in meltdown in the early days of March, they have a habit of exaggerating threats as well as perceived opportunities, as seen below. Bond rates can be expected to now stay low for a longer time, but the stock markets could make up a lot of losses as we enter 2021.

Perhaps the best news, for those prepared to take the long-term view, is that complacency in both health and interconnective trade dependencies has been replaced by better planning, safer strategies and contingency plans.

Phil Ruthven is Founder of the Ruthven Institute, Founder of IBISWorld and widely-recognised as Australia’s leading futurist.