Imagine a world in which all contributions to super during your working life were tax-free and imagine that the fund that invested these contributions was also free of taxes on their investment returns. Now imagine a world in which all withdrawals from that super fund in retirement, including income streams and lump sums, were taxed as income at normal progressive marginal tax rates.

Imagine how much higher those investment returns would have grown before retirement if the compounding over a working life of 30-40 years had operated on 100% of investments rather than the 85% remaining after a 15% tax.

Paul Keating’s original design for our super scheme in 1992 was almost this ideal system. Originally, contributions and earnings would be tax-free and retirement benefits would be taxed at 30% in recognition that this money is locked away for half a lifetime. But Keating was not prepared to wait 30-40 years before any tax was collected and so we ended up with a system whose design faults require frequent correction so that it encourages people to save for their own retirement through tax concessions, but also limits those concessions to curb the budgetary cost.

Since the system is now 30 years old, many people do not know or remember the history of this complex system.

How super works

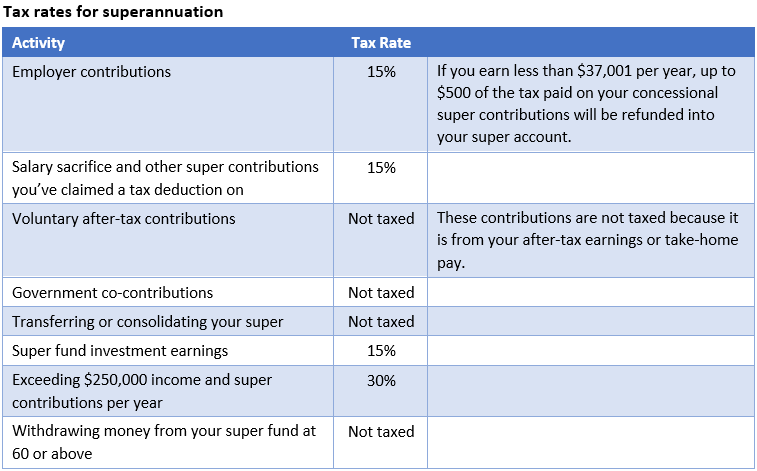

There are two ways to contribute money to super. Contributions on which tax has not previously been paid include employers’ super guarantee (SG), salary sacrifice and tax-deductible contributions. These contributions are then taxed within the super fund at 15%. But for high income earners the contribution tax is 30%. Previously people over the age of 50, could contribute $100,000 of their pre-tax salary to boost their super balance prior to retirement but because of the cost to tax revenue, these limits have been progressively reduced. Today this type of pre-tax contribution is limited to $27,500 per year for everyone.

The other type of contribution has tax paid prior to transfer to super. These contributions include the proceeds of sale of investments, businesses or personal savings. These after-tax contributions are not taxed within the super fund. Both types of contributions are invested in an accumulation fund. The income earned by the fund is then taxed at 15% until the money is withdrawn, but not before retirement.

Source: Industry Super Australia

In retirement, the accumulated super balance can be transferred to a super pension fund where the fund’s income and capital gains are tax-exempt. Super pension funds have been tax-exempt since 1992 because tax has already been collected on contributions and accumulation earnings over many years. Accumulation and pension funds are two distinct types of super funds because of their different tax treatments.

The changes under Costello

Before 2007 there was no upper limit on after-tax contributions. People with sufficient resources were well advised to maximise these contributions because, when they retired, their super pension fund paid no tax on investment earnings. Those pre-2007 rules explain why we still have a few SMSFs with more than $100 million.

In 2007, Treasurer Costello introduced strict limits on these after-tax contributions. Initially the annual limit was $150,000 but in response to the howls of protest, he allowed a $1 million contribution for one more year. That was later indexed to $180,000 per year. These contribution caps have also been progressively reduced since that time and are now limited to $110,000 per year.

Costello also eliminated the tax that members paid previously on drawing their money out of a super fund. All withdrawals, including lump sums, from a super fund are now tax-exempt after age 60. That appears to be a generous concession but in fact members paid very little tax before these changes as explained here.

Until 2017, these large funds were held in pension phase in retirement to take advantage of its tax-exempt status. The pension fund paid no tax on investment earnings and the fund member paid no tax when they withdrew their pension. Their only obligation was to draw a mandatory pension determined by their age. For someone between the ages of 65 and 75, that minimum pension is 5%. For a fund of $10 million, that would have provided a tax-free pension of $500,000 per year which had to be removed from super, but it would then be exposed to normal tax rates.

The changes under Morrison

In 2017, Treasurer Morrison introduced the Transfer Balance Cap which limited the amount that could be transferred to a tax-free pension fund. It was set at $1.6 million and looks likely to increase to $1.9 million in 2023 due to inflation. Any excess money was required to be either removed from super altogether or transferred to an accumulation fund. Most chose the accumulation fund for the concessional tax rate.

For the government it meant increased taxation revenue from accumulation funds. For an SMSF of $10 million it meant a mandatory pension was then 5% of $1.6 million in the pension fund, or $80,000. The remainder ($8.4 million) was held in an accumulation fund and is still concessionally taxed (at 15%) with no obligation to make any withdrawals, although tax-free withdrawals of any size can be made after age 60. Unsurprisingly, the ATO reports that these large funds just continue to grow.

These large funds remain a legacy of an earlier time and eventually they will disappear because death is a cashed-out event but until then, they are perfectly legal and make ideal estate planning vehicles. Worse, they continue to distort the whole debate around tax concessions flowing to super.

Morrison also introduced the Total Super Balance Cap. Once a member’s super balance reaches this cap (presently $1.7 million), the fund cannot accept any more after-tax contributions. There will be no more extremely large funds in future but arguably this is an inter-generational equity issue. Older retirees had access to very generous tax concessions but for younger people it is now simply not possible to accumulate those large super balances, regardless of their circumstances.

The current government proposals

The present government is now mulling a total cap on super across both types of funds to limit the tax concessions flowing to these very large accumulation funds in retirement. Reports suggest that if the limit was set at $5 million, it would affect 16,000 people. If the limit was set at $2 million, it would affect 80,000 people.

These people were not pleased with the changes in 2017 which introduced tax on some of their super for the first time. Given that these people followed the rules as existed at the time, they would not be thrilled with further legislation that forced them to remove any excess money from super altogether, especially as the government promised before the election to make no changes to super.

Misplaced envy about retiree tax benefits

A tax-free retirement is the result of Keating’s tax concessions provided to super funds which have existed since 1992, and not the Costello tax concessions flowing to individuals. Some would argue the whole point of compulsory saving inside a super fund that cannot be accessed for 30-40 years, IS a tax-free retirement. It actually represents a social contract. Unfortunately, it has led to considerable intergenerational envy about the tax benefits flowing to retirees, from people who do not understand how super savings are taxed. That envy would not exist if super funds had been structured differently in the first place.

If we wanted to design a better super system, we wouldn’t start from here, given the complicated patches that have been needed to fix a complex system. In any case, knowing what we know now, who would trust a government that promised tax arrangements on retirement savings to be delivered by some future government in 30 years’ time?

Jon Kalkman is a former director of the Australian Investors Association. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. This article is based on an understanding of the rules at the time of writing.