Recently, Treasurer Jim Chalmers said that Australians should have more kids. John Howard even challenged the Treasurer to bring back the baby bonus. Across the globe, leaders are concerned about declining birth rates and shrinking populations, with many government leaders seeing this as a matter of national urgency. They worry about shrinking workforces, slowing economic growth, a shrinking tax base and underfunded pensions; and the vitality of a society with ever-fewer children. Smaller populations often come with diminished global clout and greater vulnerabilities.

Fortunately, Australia is relatively well positioned, being an extraordinarily attractive destination for migrants – even though its birth rate mirrors that of other developed countries. But migrants can make a huge difference to low-population countries: when I migrated to Australia in 1988, the population was 16.5 million; today it is 26.8 million. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) projects that Australia’s population will reach between 34.3 and 45.9 million people by 2071. But we are one of the lucky few.

A major turning point

Indeed, the world is at a startling demographic milestone. Sometime soon, the global fertility rate will drop below the point needed to keep the world’s population constant. It may have already happened. Fertility is falling almost everywhere, for women across all levels of income, education, and labour-force participation. The falling birth rates come with huge implications for the way people live, how economies grow and the cultural norms we take for granted.

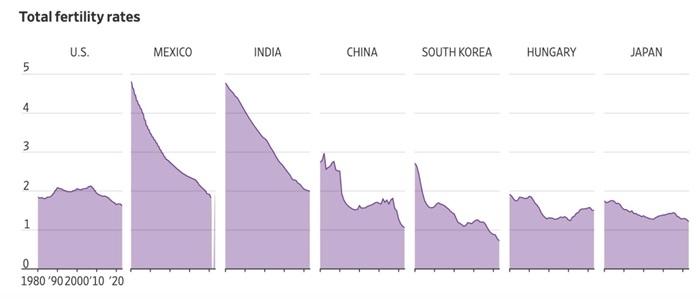

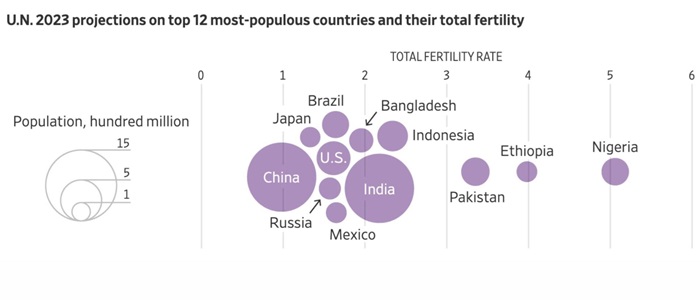

In high-income nations, fertility fell below replacement in the 1970s and took a leg down during the pandemic. It’s dropping in developing countries, too. India surpassed China as the most populous country last year, yet its fertility is now below replacement. Some demographers think the world’s population could start shrinking within four decades – one of the few times it has happened in history.

A year ago, Japanese Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, declared that the collapse of the country’s birth rate left it “standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society.” Japan’s population today is 125 million; by 2100 it is projected to fall to just 63 million, and of those, 40% will be 65 years old or older.

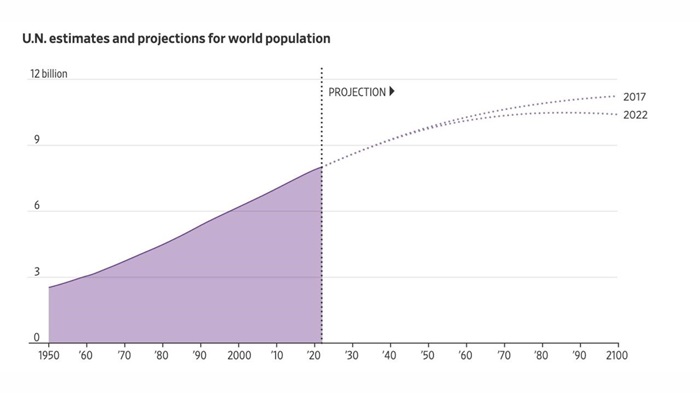

In 2017, when the global fertility rate (how many babies a woman is expected to have over her lifetime) was 2.5, the United Nations thought it would slip to 2.4 in the late 2020s. Yet by 2021, it was already down to 2.3, close to what demographers consider the global replacement rate of about 2.2. The replacement rate, which keeps the population stable over time, is 2.1 in rich countries, and slightly higher in developing countries (where fewer girls than boys are born, and more mothers die during childbearing years).

Source: Wall Street Journal

In 2017 the UN projected that the world population, then 7.6 billion, would keep climbing to 11.2 billion in 2100. By 2022 it had lowered and brought forward the peak to 10.4 billion in the 2080s. That, too, is likely out of date. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation now thinks it will peak at around 9.5 billion in 2061 and then start declining.

Source: Wall Street Journal

Historians refer to the decline in fertility that began in the 18th century in industrialising countries as ‘the demographic transition’. As lifespans lengthened and more children survived to adulthood, the impetus for bearing more children declined. As women became better educated and joined the workforce, they delayed marriage and childbirth, resulting in fewer children.

But now, it appears that birth rates are low or are falling in many diverse societies and economies.

Some demographers see this as part of a ‘second demographic transition’, a society-wide re-orientation toward individualism that puts less emphasis on marriage and parenthood and makes fewer or no children more acceptable. If people prefer spending time building a career, on leisure, or relationships outside the home, that is more likely to conflict with having children.

And that’s not just in Western countries. Urbanization and the internet have given even women in traditional male-dominated developing world villages a glimpse of societies where fewer children and a higher quality of life are the norm. People everywhere are plugged into the global culture.

Sub-Saharan Africa once appeared resistant to the global slide in fertility, but that too is changing. The share of all women of reproductive age using modern contraception in that region grew from 17% in 2012 to 23% in 2022, according to Family Planning 2030. And once a low fertility cycle kicks in, it effectively resets a society’s norms and is hard to break.

Source: Wall Street Journal

Economic implications of the baby bust

With no reversal in birth rates in sight, the attendant economic pressures are intensifying. Since the pandemic, labour shortages have become endemic throughout developed countries. That will only worsen in coming years as the post-crisis fall in birth rates yields an ever-shrinking inflow of young workers, placing more strain on healthcare and retirement systems.

The usual prescription in advanced countries is more immigration, but that has its own problems. As more countries confront stagnant populations, immigration between them for ‘skilled migrants’ is a zero-sum game. Historically, Australia has sought skilled migrants who enter through formal, legal channels, and we have been fortunate enough to have plenty of candidates to choose from. But many developed countries, like the US and the UK, have been resisting recent inflows of predominantly unskilled migrants, often entering illegally, and claiming asylum. High levels of immigration can also foster political resistance, often over concerns about cultural and demographic change. Unfortunately, it is no coincidence that the rise of the extreme right-wing in countries like Germany, Sweden and Italy has followed on the heels of very large intakes of migrants, often from countries that do not share similar cultures.

Paul Zwi is a Portfolio Strategist at Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.