The impact of digital innovation has been felt in many parts of the global economy and the financial planning sector is not immune. Recent turbulence in the advice industry, coupled with an increasingly engaged and digitally-aware public, has created the perfect environment for digital disruption. Technology has a key role to play in improving the availability and consistency of financial advice and one area in particular that has been receiving a lot of interest is the use of roboadvice.

While the term robo-advisor could be taken to imply a robot or algorithmic digital tool designed to perform all of the tasks of an adviser, Australia has yet to see a roboadvice tool which comes close to offering the full services of a traditional financial adviser. The scope and sophistication of financial planning software and online calculators is increasing, but they are still essentially support tools or algorithms. If we look to the US, where the phrase robo-advisor was coined and where they have had the most success, we see that the majority of these services focus on portfolio construction and rebalancing. However, this activity is a very narrow subset of what is usually referred to in Australia as advice – that is, assessing an individual’s financial position and proposing holistic strategies to improve that position – so we are a long way from replacing human advisers with machines.

Benefits and limitations of the robo-advice model

Complex advice algorithms have many benefits, but they also have their limitations. To illustrate the challenges in bridging the gap between algorithmic roboadvice tools and the more holistic work of a financial adviser, we have explored a typical, seemingly simple, advice scenario.

Suppose an advice client currently has a mortgage on their family home and is considering the following two options:

- Making prepayments on the mortgage to pay if off sooner; or

- Entering into a salary sacrifice arrangement to build up their superannuation savings.

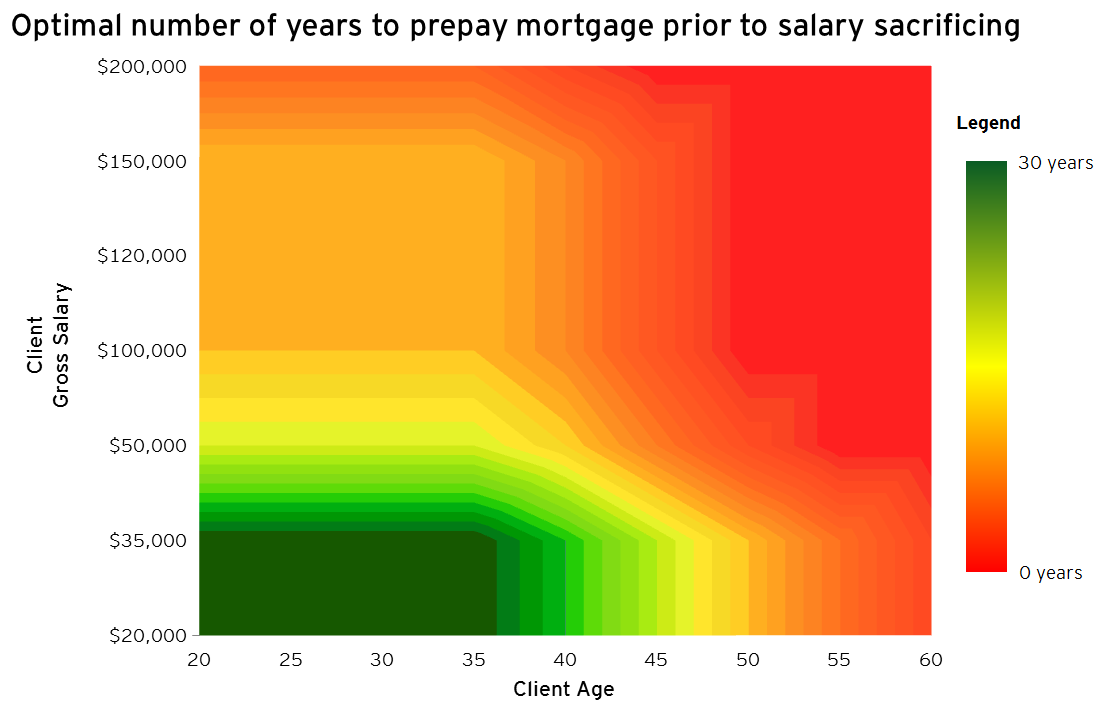

To provide insight into the level of complexity required to deal with what appears to be a relatively simple question, we illustrate the results of our algorithmic calculations in the figure below.

Note: This chart was constructed using many different assumptions about various client types and economic assumptions and should not be relied upon for financial advice. It is provided for illustration only. For example, we have assumed that client age is a proxy for remaining mortgage term.

As the chart shows, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. For many people – such as those who are closer to paying off their mortgage and are on higher marginal tax rates – paying off their mortgage with free cash flow may not be the optimal strategy. They could stand to be in a better financial position at retirement if they were to salary sacrifice this free cash flow instead. Conversely, younger individuals on lower marginal tax rates may be better off financially if they elect to prioritise paying off their mortgage.

Not a trivial calculation

Even by restricting our analysis purely to the objective of maximising net wealth at retirement, arriving at the best solution for the client is not a trivial task and requires the exploration of multiple scenarios to arrive at an appropriate strategy. While this can be achieved with commonly available planning tools, it is a time-consuming process, especially if a high degree of accuracy and consistency is required. This provides an opportunity for ‘next-generation’ algorithmic tools that can perform the mechanical operations quickly and in a way that gives the adviser confidence in the accuracy and consistency of the results. The adviser would then be able to generate a reliable strategy and talk the client through it in one sitting.

However quick and accurate they may be, algorithms on their own are not enough as there are many variables that must be addressed, some of which are subjective. For example, the algorithm used to generate the output above does not capture liquidity preferences, the risk of breaks in employment, possible changes in salary, bequest motives or other sources of uncertainty, such as a potential spike in interest rates. While some of these considerations can be addressed by developing smarter algorithms, others require higher level thinking. An example of this would be factoring in an individual’s preference to reduce their leverage as quickly as possible, to achieve greater peace of mind. This is more than a numerical optimisation exercise; it requires human-like intelligence.

Who will be the winners?

What does this mean for the future of robo-advisors? We expect to see the development of greatly enhanced algorithmic tools to support advisers, with benefits including:

- Speed and efficiency of advice

- Reduced cost to serve and increased proportion of the population serviced by the advice industry

- Increased consistency of advice and the potential to enhance documentation and record keeping

- The retention of advice data in readily-accessible digital formats to assist with compliance functions, client engagement and trend identification.

As for the term roboadvice, while great for headlines, it is a little unhelpful when it comes to understanding the reality of the advantages that automated algorithms can bring to the advice industry.

We are still many years away from robo-advisors having sufficient artificial intelligence to replace financial advisers. However advisers do need to acknowledge that they are part of a rapidly changing industry which is adopting algorithmic tools of increasing sophistication. This is both a great opportunity, as well as a threat to those unable to adapt quickly. Early movers who take advantage of these advances in technology will attract more clients, increase productivity, drive down costs and serve previously unadvised segments of the market.

As with many technological advances, the ultimate winners are likely to be the end consumers. With such a large portion of the population currently unadvised, and no let-up in the complexity of our financial system, this can only be a good thing.

Steven Nagle is a partner in EY’s Oceania financial services practice. Anthony Saliba is a manager in EY’s Oceania actuarial services practice.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors, not Ernst & Young. The article provides general information, does not constitute advice and should not be relied on as such. Professional advice should be sought prior to any action being taken in reliance on any of the information. Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.