There is one significant observation that is neither well reported nor well understood. Readings of macro numbers sporadically report on it, but they do not delve into its significance or what it means for the flow of investment capital.

What is it?

It is the relentless strength of the USD, the mighty greenback. USD strength shows that the US economy is excessively calling upon and draining the developed world’s capital.

The massive US fiscal, trade and capital account deficits are significantly (and disproportionately) funded by foreigners. The US economy dominates developed world growth, but it requires or feeds off continuous drawings of global capital.

This funding will continue for as long as the US corporate sector shows superior technological advancements over international peers.

A moribund, ageing and over-regulated Europe provides little investment alternative to that of the US. And until Asian economies develop the ability to challenge the US in terms of liquidity and political, accounting and legal security, Australia will continue as a capital provider to the US.

The consequences are examined below.

US budget deficits and its debt are consuming the world’s capital

Whilst the US economy approximates 30% of world GDP, its government now accounts for 32% of world government debt. Further, as its debt has grown it has burnt through foreign capital providers with Japan, China, UK and even Russia, each of which were large US bond holders at various points over the last 25 years.

The current budget (2024) is presented in the next chart and it shows a deficit of US$1.6 trillion. Inside that deficit, some US$763 billion is interest. This indicates that the US is currently paying (on average) about 2.1% for its debt.

Source: US Treasury, Monthly Treasury Statement, July 2024

It is disturbing to note that if the US government was to pay its current cash rate (4.75%) for its debt, then the interest bill would rise to US$1.5 trillion. Simply stated, the US government cannot afford to pay current short-term interest rates and therefore the Fed needs to get interest rates down and quickly.

The US economy is dynamic, and it has propelled world growth prior to the entry of China, and now India, as alternative growth engines. The US stands well above the developed world in terms of both technological and medical developments, but it has drawn immense sums from its trading and investment partners to do so. It is stunning that 346 million citizens drive a world economy of 8.2 billion people.

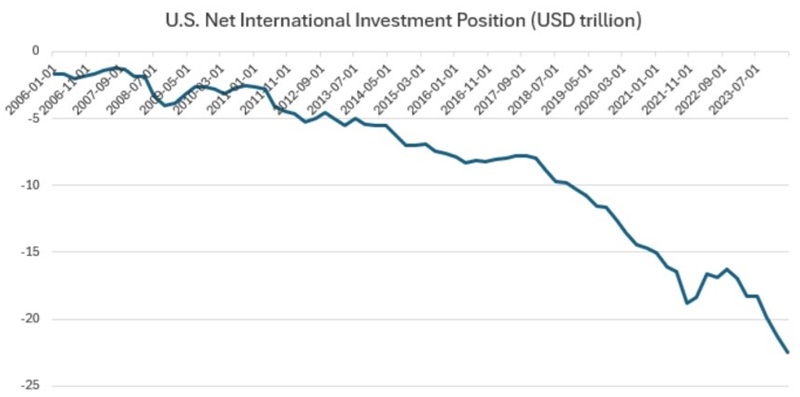

The next chart is crucial: it tracks the net international investment position of the US over the last 20 years. This position measures the difference between US overseas owned assets and those held by foreigners in the US. It measures shares, bonds, corporate debt and property etc. and shows that the difference has grown from US$1.66 trillion (deficit) in 2005 to US$22.5 trillion (deficit) in March 2024. About 50% of this net capital deficit is held by foreigners in US bonds.

The transmission effect of these capital flows that fund US government debt is that the USD rises to meet the constant foreign currency inflows. It is a self-perpetuating positive loop for the USD. The more the US needs capital and funding, the higher its currency goes. So too do speculative assets that benefit from US pricing – gold and bitcoin are prime examples.

For Australia (in particular) and other developed economies, this has become a significant problem as the US draws our capital to sustain its growth. That growth is important for the world economy until the developing world takes over.

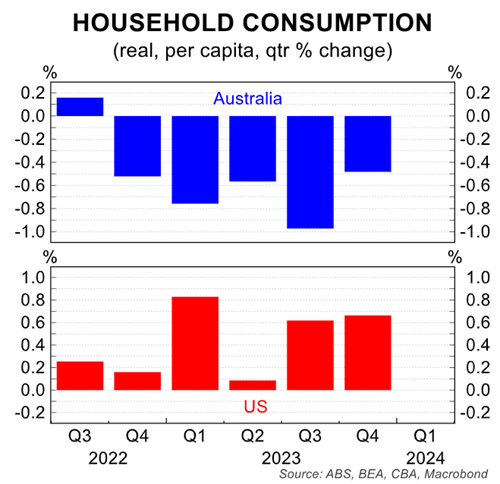

Indeed, this is shown clearly in the next chart that compares Australia’s real household consumption growth with that of the US household sector. US household consumption has driven both the US and the world economy.

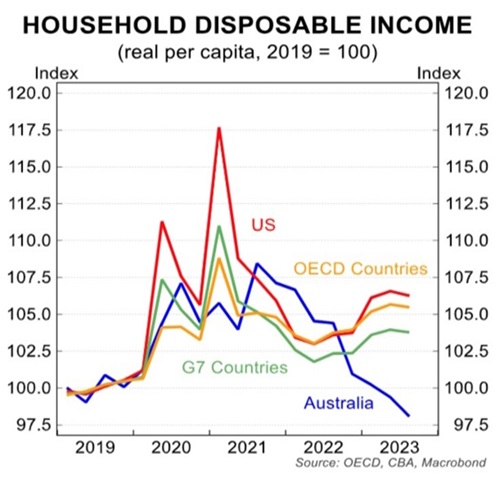

US consumption growth is superior because it has achieved real disposable income growth. Australia’s real disposable income has declined since the covid pandemic.

US consumption has also driven the profitability and therefore the valuations of US listed corporates compared to the rest of the world. Indeed, the US market now represents 72% of the world equity market index. That feature alone draws in massive quantities of index invested capital residing around the world in passive pension funds.

Weak AUD has consequences

So where does Australia sit in the complex funding of the US economy?

With A$3.7 trillion (US$2.5 trillion) of super assets, our superannuation funds are 30% larger than Australia’s GDP. Our large industry funds have no choice but to invest in the US economy. Therefore, they will continue to contribute to the US economy by investing enormous sums into US Treasuries, corporate debt, equities, and infrastructure.

To do so, our super funds must sell AUD to buy USD. This means our currency will remain under selling pressure until the US economy falters or our capital managers can find other regions in which to invest.

Importantly, the international currency market will probably not revalue the AUD against the USD. Our credit rating, our trade surplus, our budget surplus, and our superior national debt position will have little effect on the value of the AUD. Therefore, our investment thought process must adopt as a likely scenario a weak currency outlook and its consequences.

Conclusions and observations

- Australia's currency will continue to be undervalued which means that imported inflation remains a concern - cash rates will be held above our international peers;

- Whilst the RBA will cut interest rates in 2025, it must be at a lower rate than those seen offshore – to support the AUD;

- Mortgage rates will decline through 2025 giving relief to the “mortgaged” household sector – providing an uptick to Australian economic growth in 2025;

- Australian inflation will meander downwards, and more cost-of-living support will be needed - expect significant pre-election packages.

- Post the US election, the funding of the US economy will become a focus for bond markets in 2025 – any upheaval in bond markets will see a swift return to QE;

- If QE returns as policy in the US, expect Europe to follow. The developed world has far too much debt and cannot support higher interest rates; and

- Income returns (over capital growth) will dominate returns to investors – the outlier being the US equity market which continues to draw in passive capital.

My conclusions suggest a volatile outlook for markets in 2025 as the world once again is forced to assess the impacts from and policy responses required to deal with enormous debt levels.

Australia’s debt problem resides in a part of our household sector. Our total household debt is too high, in a sector of the community which is the core of our future – the youth. The government needs to respond with smart assistance programs that do not further fuel house price rises. An intricate problem that is not being properly debated.

The world (particularly the US) debt problem resides in the government sector and it is most likely that the Fed will revisit its policy response adopted in the 2018 bond tantrum. Other central banks will then surely follow.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.