Introduction. This article was originally published in 2015, and is reproduced here after a friend told me he was looking to buy an apartment in a holiday resort. One of the attractions is the ability to stay in the apartment when it is not rented out for short-term holidays. He said there was no point leaving money in the bank earning nothing and shares are too risky. This sounds like a scenario many readers contemplate as they look for income in new places.

I'm sure he thought I would smile pleasantly and he would drive off to buy his dream with a view. I sent him this article and he's definitely having second thoughts. I have not changed any of the numbers so please read it knowing it is seven years old. The arguments remain valid. These resorts are a crap shoot.

Coincidentally, I stayed on the Gold Coast last week, this time further south than usual in an apartment at Bilinga, near Coolangatta. From there, the thousands of towers of Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach loom large on the horizon, a mass of short-let apartments ranging from the luxury to the downright trashy. The experience of owners no doubt covers the full range from wonderful to woeful, but anyone buying into a resort for short-term let should know what they are going into ... mainly financing the holidays of other people.

***

Explore the rear entrance of an apartment hotel or resort that is more than five years old and take a look at the contents of the skips in the lane outside. They are often full of sofas, dining chairs, mattresses and televisions. Seven years earlier, when the proposal for a shiny new building was just a model in a display apartment for off-the-plan sales, hundreds of dreamers signed up to buy apartments. They also agreed to a furniture package for $40,000 to allow the building to operate as a hotel or resort. After years of people on holidays staying in the rooms, jumping on the sofas and leaning back on the chairs, the furniture needs replacing. Over the five years, that’s another $8,000 a year of costs to write off for each owner. It’s not such a dream now.

A few years later, the apartment will probably need a new bathroom and kitchen. How many years of income will that cost?

If you don’t believe a sofa lasts only five years, you’ve probably never owned one of these short-let apartments. Hundreds of kids and honeymooners and party animals have enjoyed themselves on the furniture while on holiday. Have you ever watched coverage of schoolies week?

The most misleading number in investing

Real estate agents quoting gross yields on residential property are using the most misleading number in investing. The costs associated with residential property consume most of the income, leaving uninformed investors blind to the actual returns until the expenses start to come in. In an era where the professionalism of financial advisers is slammed daily in the media, many property agents get away with poor disclosure without comment.

Obviously, this is not a marginal asset class few people care about. Residential real estate in Australia is worth $5.8 trillion, and it dwarfs listed equities of $1.6 trillion and superannuation of $2 trillion. It accounts for over half of Australia’s wealth (see CoreLogic Housing and Economic Market Update, April 2015).

Why are gross versus net yields so important for real estate?

Invest in a term deposit at 3% and you will earn 3%. There are no other costs involved. In equities, the effective yield earned can be better than the quoted dividend rate when imputation credits are added back. But residential property is the opposite. Net yields should be the main focus because expenses are high and unavoidable, even if the property is left empty.

A typical commentary on a real estate ‘entertainment’ programme goes like this:

“Is this a buy or a sell? It’s a one-bedder only 10 kilometres from the centre of Sydney, close to buses, 65 square metres, asking $750,000, would rent for $650 a week.”

“Well, the starting point is you don’t want to be out of this market,” replies the agent confidently. “This place will be worth $50,000 more in a year – that’s $1,000 every week. And look, $650 a week is about $35,000 a year, that’s a yield of 4.5%. Where can you get that today?”

Can you imagine what ASIC would do to a licensed adviser who spoke like that, or included it in an offer document? Prices do not always rise, and that yield is not available by buying that apartment.

CoreLogic quotes rental rates of 3.7% for ‘combined capitals’ across Australia, but this number is gross rental yields (for example, see page 7 of above-linked report). It’s the number the industry loves to talk about. But even if we put aside stamp duty, legal costs, borrowing costs and vacancies, what about the regular costs of owning a property? These are the ongoing drains on income that are often overlooked. According to a Reserve Bank of Australia Research Paper, ‘Is Housing Overvalued’ (June 2014), the running costs of long term rental properties are 1.5% per annum, and transaction costs of 7.3% averaged over ten years are 0.7%, giving costs of 2.2% per annum.

That takes the net yield to 1.5% before allowing for repairs and maintenance. Reality is completely different than the real estate brochures and entertainment programmes convey.

How do management rights work?

When a large apartment building is constructed, the lots or units are purchased either by people who want to live in them (owner occupiers) or let them (investors). The ‘management rights’ to the building are sold by the developer, which gives the manager the right to charge a fee to look after the building and in some circumstances, run a letting scheme. The manager estimates how much income the building can generate when deciding how much to pay for the rights.

Of course, there are hundreds of thousands of different schemes in Australia, ranging from small premises run by mum and dad to professional managers (including listed companies) who may pay up to $15 million to manage a large, prestigious building by the beach with great views. The management rights might include running a restaurant, a reception centre, housekeeping, a real estate business as well as the letting and maintenance. Income includes payments from the body corporate, plus owners who enter a letting agreement pay a percentage of the letting charges, say 8% for long term letting and 12% for short term. The vast majority of apartment buyers in a hotel or resort sign up with the manager because there are efficiencies in one person managing the whole building. But what the buyer does not realise is that every change of a light bulb, every adjustment of the remote control, and every time the room is cleaned is a money-making opportunity to recover that $15 million.

Higher income, higher expenses

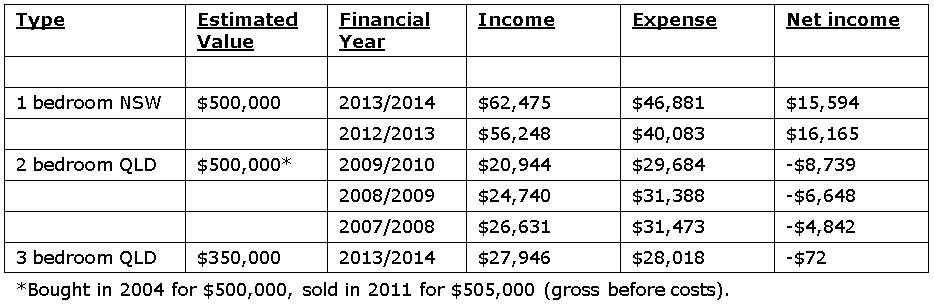

An apartment costing say $500,000 might rent permanently for $500 a week, but as part of a hotel, $250 night in high season. How can this not be a better deal? Consider these actual examples of well-established apartments in hotel or resort schemes targeted at short-term letting:

Table 1: Extracts from tax returns for typical short-term letting apartments

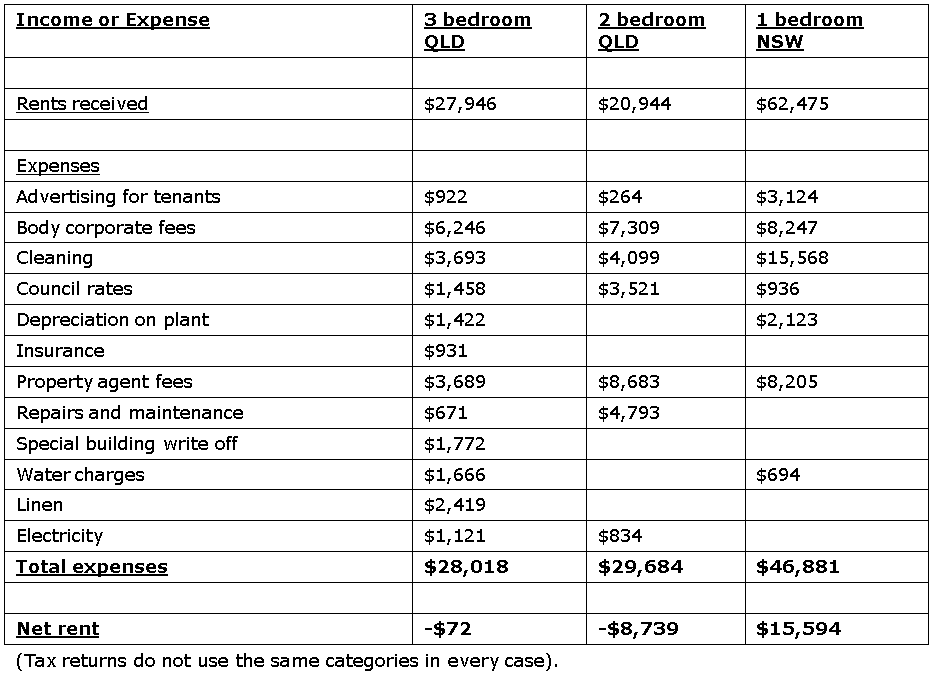

The expenses from short-term letting are far more than permanent, especially costs such as cleaning and replacing equipment. Owning an apartment for short-term letting can be an annoying experience of monthly expenses to maintain the apartment to the standard required by the hotel or resort manager. Here is more detail from the tax returns of these apartments:

Table 2: Detailed income and expense returns

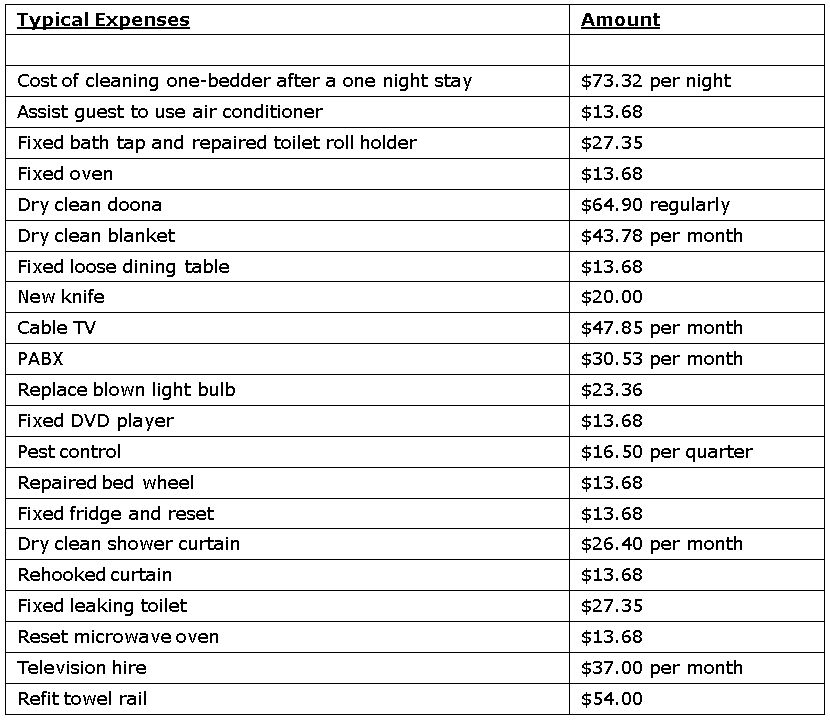

It’s hard to believe a small apartment can incur $47,000 in costs a year. People who put their apartments into these letting pools are probably prepared for some of the same costs as long term rentals, such as strata fees and council rates, but who expects regular costs such as these:

Table 3: Examples of specific expenses in short term letting

It’s a monthly crap shoot. The owner pays $360 a year for the phone system, and could buy the television for a year of hiring fees. The dry cleaning can be $100 a month. The cost of cleaning a one-bedroom apartment after one night is an unbelievable $73. How long does it take to clean a small apartment in a building with 200 such apartments? If you think the management fee should cover the quick visits to the apartment and complaints by guests, read the fine print. There is no way of knowing how often a light bulb is replaced or a bed cover dry cleaned. Who dry cleans a shower curtain every month? That $1 light bulb costs $23 to replace. This is a big money earner for the manager. A guest might stay for one night and after expenses such as booking agent fees, advertising levy, housekeeping and repairs, little is left for the owner. It’s not worth the wear and tear on the apartment.

Who cares, capital gains and tax deductions are more important than income

Many investors may consider the income to be a minor part of the expected return, especially if they realise it’s only likely to be 1.5%. Residential property prices in Sydney were up 14% in the year to March 2015, so a few dollars in expenses is tolerable (although it was less than 5% per annum for the decade before 2015).

There’s a problem here as well with short term letting. Most owner occupiers do not want to live in a building where the majority of other tenants are holiday-makers. These visitors are out to have a good time. They party late at night, crash their suitcases into the lifts and walls, drag their wheels across the floorboards or carpets, return from the beach in their towels and drip on the furniture. The kitchen benches get scratched, the carpet must be cleaned regularly and equipment is stolen. People who assume guests look after the room in the same way they look after their own home don’t know how some people live. A permanent resident living in a building does not want to battle a lift full of suitcases every time they leave their apartment.

So the secondary market sales of these apartments are usually not to owner occupiers, and the building gradually becomes dominated by short term lets. The major buying force that pushes up the price of real estate, the person buying their dream home, is not in the market. The premises are also subject to intense wear and tear, and the foyers are full of holiday brochures and bags and screaming children and people waiting to check in or out. So these apartments are worth less than in owner occupied buildings. Investors ask to see the net return after five years, the tired furniture and dirty carpet, and the income yield is not enough to create demand unless the price is relatively low. In many locations, these apartments in hotel schemes are the cheapest in town. It’s no surprise the two-bedder listed above made a large capital loss after expenses (stamp duty, agent’s fees, legal fees) despite seven years of ownership.

At least the loss is a tax deduction, able to be offset against other income. But buying an asset to create a loss and a tax deduction is a strange way to build wealth. Many investors talk about the ‘tax deduction benefits’ as if that is a good aim in itself. The only reason it’s a tax deduction is because it’s a loss.

OK, but at least I can holiday there

How about justifying the purchase by using the apartment once a year for a holiday? Forget it. The time of the year when the rent is the best is also when the owner wants to use it. Don’t confuse an investment with a lifestyle decision such as a holiday. Anyone who wants a week in a resort should pay for a week in a resort, not a year of problems owning the place.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. This article is for general educational purposes about a specific market segment, and individuals should obtain their own professional advice.