At first glance the land lease business model appears like a way to get cheap housing that is also a good investment. But regulatory quirks mean we all pay.

One of the hottest plays in residential real estate investment is the land lease community. Currently, this model of ownership houses 130,000 Australians and there are many more projects in the pipeline.

So what’s it all about?

This article is my attempt to wrap my head around the business model and understand where the rabbit goes in this financial magician’s hat—because if it is a cheaper option for residents, then how is it also a better investment for landlords?

Who exactly is paying?

The land lease model is essentially that of a caravan park. In Queensland, the relevant legislation for these communities is the Manufactured Homes (Residential Parks) Act 2003, with each state having its own legislative framework. Some land lease communities are (or were) caravan parks. In the United States land leases are called ‘manufactured home estates’.

Many companies are active in this sector, such as Ingenia, GemLife, Hometown, Palm Lake, and Sea Change. Large institutional investors are also taking an interest.

Halcyon is a big player and was recently acquired by Stockland for $620 million. There now seems to be a huge financial appetite for investment in this model, just as there is for build-to-rent apartments.

Here’s how they describe the land lease model:

…you purchase your stand-alone home and sign a lease (Site Agreement) to pay rent (Site Fees) on the freehold land on which your home sits. The land remains the property of Stockland. Under the legislation (relevant to the state the home is located in), you hold your land lease in perpetuity, meaning it lasts the life of your ownership. The Site Agreement is your contractual right to occupy the land and also gives you non-exclusive use of the community’s common areas and communal facilities.

This site agreement style of lease comes with the obligation of an ongoing rent payment, which is often a different amount for singles and couples. Some are perpetual leases, but others expire after 50 or 99 years, and the site agreement can be traded like any other property right. There is usually no subletting allowed.

Because of this lease arrangement, rather than a property title, there is currently no way to borrow money to buy a home and lease bundle in land lease communities. So they are typically marketed towards retirees, with often minimum ages of 50 years and bans on children residing in the community.

They are essentially retirement villages. And I think that much of the analysis that follows applies to retirement villages in general.

Land lease communities seem to be delivering for many residents. They also seem to be delivering for investors.

If land lease projects make better returns for developers and landlords, how can they also be cheap for residents compared to buying or renting freehold property?

Regulatory quirks relied on for the business model

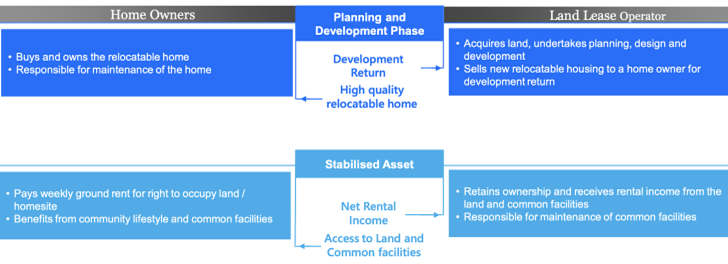

Here’s how Stockland explains its land lease business model.

In the development phase, land lease projects are like any other freehold development project, but what is sold are called site agreements, not freehold titles.

In the ongoing asset ownership and management phase, land lease projects look like any other build-to-rent project.

How does this lease arrangement enable a housing project to earn sales revenue and rental returns while still being of value to residents?

Tax and welfare quirks

As the Halcyon website explains:

You may be eligible for rent assistance if you receive a pension through Centrelink. This can reduce your Site Fee by around $60 a week. (Your Site Fee is subject to an annual CPI adjustment or a yearly formula review to factor in any extraordinary rises in government charges, such as rates). A market review of your site rent takes place every three years.

The trick here is that although owning a site agreement means you ‘own’ your home, it is also classified as a lease. So pensions get extra money to ‘own’ this type of home because the welfare system pretends that they are renting it instead.

Currently, rent assistance is $174 a fortnight (maximum) for an age pensioner couple household. For a typical land lease, with a $250 per week ‘rent’, that covers about 35% of the ongoing cost. There are no other management costs for shared facilities, as these are wrapped up in this one rental amount.

Which is a little weird. Why can’t apartment owners just rename their body corporate fee a lease? You would own the physical apartment, but not the ‘land’ and then rent the land from the body corporate at a rate that covers exactly the same things as a body corporate fee.

Another quirk is that land value taxation is assessed on the total project as a single site. In practice, this means the per-dwelling land value is much lower than comparable freehold properties. A few quick and dirty calculations using land valuations from QLD Globe suggest the land value assessment for some estates is between $30,000 to $80,000 per dwelling, whereas nearby homes (admittedly on larger lots) have assessed land values at $200,000 to $400,000 per dwelling. For a landlord, this is a huge tax benefit compared to owning a physically near-identical housing estate that was individually freehold titled. Such benefits of lower land value rating can extend to also to lower council rates, which are charged to the landlord and recovered from residents in their site rent.

One big tax quirk is that stamp duty is also not payable on trades of site agreements. Even though site agreements can cost as much as nearby freehold property. So this further reduces the upfront cost of ownership for each resident by a few per cent, a gain that can be shared between landlord and resident.

There are a lot of labelling games in this business model.

Planning and physical quirks

Land lease projects look different. I’m picking on Queensland’s biggest land lease landlord here, but check out the aerial imagery. Here’s Halcyon Glades at Caboolture.

Source: Apple Maps

Here’s Halcyon Lakeside at Bli Bli.

Source: Apple Maps

Here’s Vision by Halcyon at Hope Island on the Gold Coast.

Source: Apple Maps

I don’t have to mark where these projects are because they are obvious from their much higher density than neighbouring residential estates.

I suspect but don’t know for sure, that such densities would otherwise be uneconomical and also not allowable under local regulation. Streets are often exceptionally narrow and built to lower standards. This makes sense, as they are not public roads but internal driveways. Setbacks that would otherwise apply to detached housing do not apply, and generally much smaller homes of around 120-150sqm are built. Since older buyers generally don’t value larger homes or backyards as much as younger buyers do, these design concessions don’t seem to affect sale prices as much as they might in the broader market.

Controversially, land lease communities are often allowed in rural zoned areas, where legacy zoning laws for caravan parks apply.

Taking advantage of these often-illusory differences between a land lease and a freehold subdivision makes financial sense. If you can get 300 land lease homes on a site when it is land leader, rather than a dozen rural housing blocks as freehold, you are way in front.

How much does it cost residents?

I was surprised that buying a site agreement in a land lease community is not cheap.

Here’s a two-bed, two-bath 128sqm home on what looks to be less than a 200sqm lot, seeking “offers above $990,000” for a new site agreement with the dwelling included on the Gold Coast. Yet when I search online, there are nearly a thousand detached homes on the Gold Coast for a lower price, often in better locations with pools and large lots.

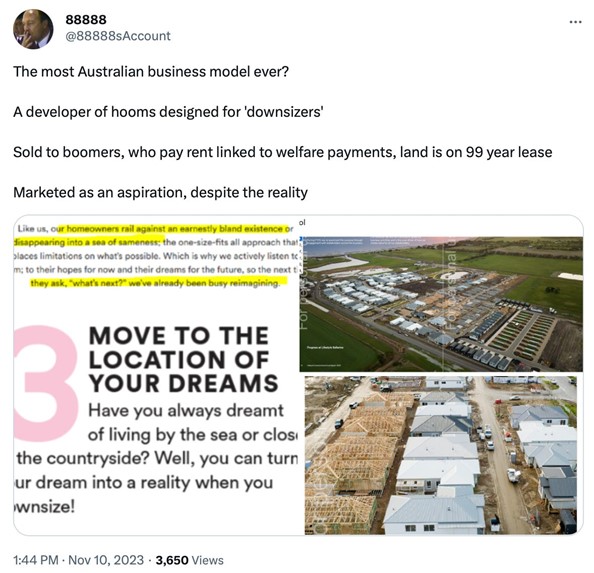

Many people are sceptical that land leases are cheap on a like-for-like comparison of size and quality, as this critical tweet noted.

I suspect that in terms of ongoing cost, a ballpark financial comparison for residents of freehold ownership, rental, and a land lease agreement, looks something like this.

Freehold ownership

Home price = $700,000 (including stamp duty) or $35,000 per year interest cost at 5%

Rates/insurance = $6,500/yr

TOTAL = $41,500

Land lease

Site agreement = $900,000 (no stamp duty) or $45,000 per year interest cost at 5%

Site fee = $13,000

Building insurance = $2,000

Minus rent assistance = $4,500

TOTAL = $55,500

Rental

Annual rent = $30,000

Minus rent assistance = $4,500

TOTAL = $25,500

So the premium is probably about $10,000-$30,000 per year above the alternatives. Typically, site agreements rise in value with the general housing market, so that makes it much better than renting.

This comparison ignores the services included. Some communities have free golf course access as part of the deal. Most have extensive community facilities and are usually gated and more secure than other alternatives. The simplicity of the package deal of bundling all ongoing costs and management into a single rent payment can be appealing and valuable, and it seems that residents value all of this at more than the $14,000 per year premium over owning a freehold house.

Who pays?

It looks like there aren’t clear cost savings for residents, even after rent assistance and a lack of stamp duty are factored in.

Costs are often higher than owning a nearby freehold home. What you get for those higher costs are extra services and shared amenities, security and simplicity. From what I hear, there is often a great social and communal atmosphere. The trade-off is density (and sometimes less privacy) for services and community.

That’s worth it for some people.

But all of us pay. If all of the 130,000 land lease residents got the full rent assistance amount (which they don’t), that would be about $420 million of the $5 billion in annual rent assistance paid annually by the Australian government.1

Without this rent assistance, the value of these site agreements, and the ability to charge the usual $250 per week in site rent, would be greatly diminished.

Not surprisingly, the recent increase in rent assistance was reported as “a boost for land lease communities.”

Investors also benefit from the physical flexibility of building smaller, cheaper homes, giving up less land for road circulation and so forth. The lower land value assessment helps with keeping ongoing taxes and rates down too.

One downside for investors is the lack of mortgages currently available, which limits their buyer pool. No doubt there are plenty of incentives out there to create a financial instrument that achieves the same outcome.

Future outlook and risks

One risk to tenants concerns the setting of rents. As the price of alternative rental and home purchase rises, there is nothing stopping rents within land lease communities from being increased to match.

This has been an issue historically. The relevant legislation has been updated and reviewed in the past decade in most states to curtail overly ambitious rental increases and problematic mark-ups from landlords on-selling electricity and other services within communities.

But broadly rising rents in the housing market mean that this is a concern again.

Overall, the business model seems to be built around the quirks of the tax and planning systems, meaning we all pay. As my Twitter friend pointed out, this is probably the most Australian business model ever.

1 That's 40,000 households getting the $174 per fortnight couples rate and 50,000 single households getting the $184 singles rate (rent assistance rates from here).

Dr Cameron K. Murray is Chief Economist at Fresh Economic Thinking. The original article can be found here. Subscribe to his written work at Fresheconomicthinking.substack.com. This article is general information.

His new book, The Great Housing Hijack, will be released on 27th February 2024 (you can pre-order now). If you want to understand the economics of housing markets and why everyone claims to want affordable housing, but no one wants cheap housing, this book is for you.