When Labor came to power in May 2022, housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne were already higher than in almost all other developed world cities. Since May 2022, the crisis has deepened as dwelling and rental prices have continued to rise, along with interest rates, thus generating a serious rental crisis and a slide in the affordability of detached houses, especially in Sydney and Melbourne.

Though much less of a focus for Governments than the rental crisis, the first homeowner affordability crisis is nonetheless of huge significance. For younger households wanting family friendly housing and to get a foot on the property ownership ladder, their inability to do so is a catastrophe.

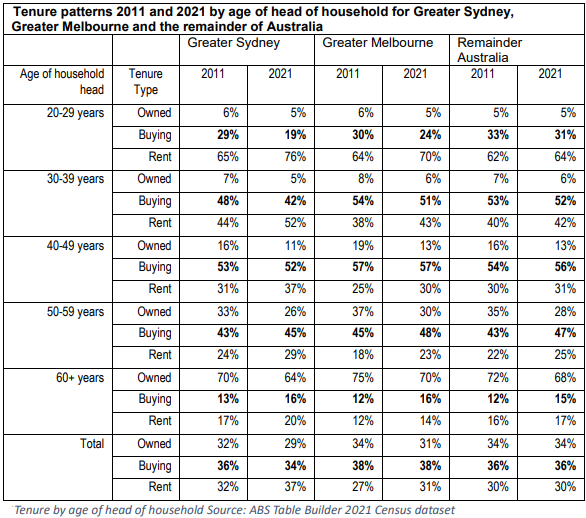

By 2021, the share of households in Sydney headed by a 30–39-year-old who were renting had reached 53%, and 37% for 40–49-year-old household heads. (Note that census data also refers to household heads as reference persons.)

Melbourne was trending in a similar direction, though from a lower base. The situation has worsened since 2021 as housing prices have continued to rise.

The result is that, for many of these households, home ownership is a receding dream. It is being replaced by continuing rental. Given how important home ownership is in retirement years, it implies a spectre of financial insecurity in this phase of life.

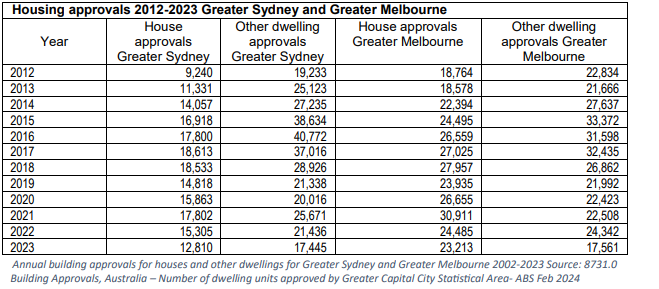

Federal and state governments have committed massive funds, especially to fix the rental crisis. Yet despite this commitment, building permit approvals for medium and high-density dwellings in Sydney and Melbourne were lower in 2023 than a decade ago. They continued to fall in 2024.

How could this be?

The dominant explanation, held by governments, planners and most expert commentators is that current zoning laws and building approval procedures are restricting development. If they were loosened, so it is argued, much more medium density housing will result in middle suburban areas. Similarly, if constraints on high rise apartment buildings are eased, many more of these projects will start.

According to this dominant perspective, both resident and new migrant demand can be satisfied, notwithstanding the huge increase in the migrant influx in 2022 and 2023. Net overseas migration to Australia was 433,150 in 2022 and 547,267 in 2023. This compares with near 250,000 each year prior to the 2019-2020 pandemic (which was itself a steep increase from the long-term average from 1950 to 2005 of 88,700)1. Some 67.5% of this net influx reside in NSW and Victoria (which comprise 57% of Australia’s population), the great majority locating in Sydney and Melbourne.

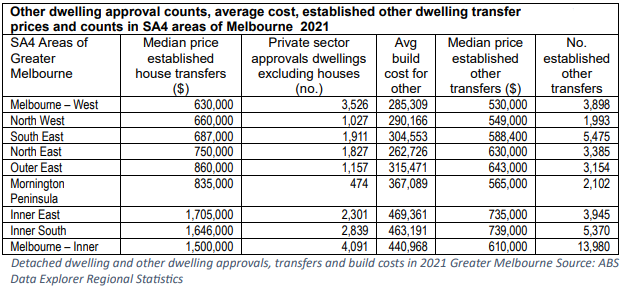

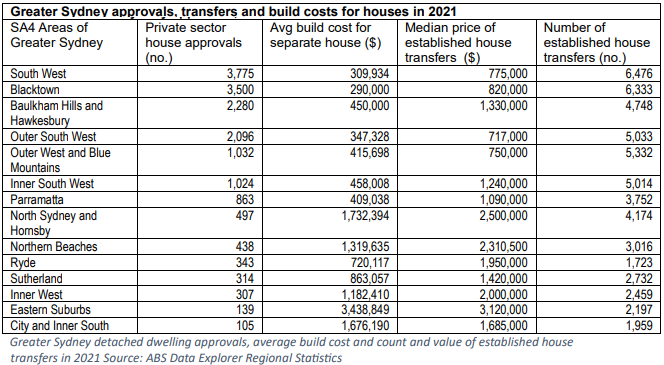

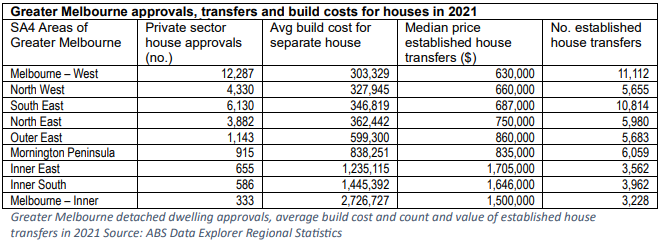

However, irrespective of zoning laws and building approvals, the densifying strategy is not working. We show that in the current setting developers cannot make a profit from providing affordable rental accommodation, either from medium density projects in the middle suburbs (the ‘missing middle’) or from high-rise inner-city apartment projects. In the case of the ‘missing middle’, developers can’t build such units or town houses because of escalating site costs, mainly due to the high price of the land on which they have to be built.

Site costs continued to escalate because of competition for detached housing not just from aspiring first homeowners. The escalation is also from a large cohort of financially strong upgraders who are switching houses in pursuit of the tax-free capital gains flowing from the price escalation of higher end houses. Investors, too, are adding to the demand. In addition, there is a lagged demand for the purchase of detached housing from earlier arrived migrants. This latter source is very important but has not been recognized in the housing literature.

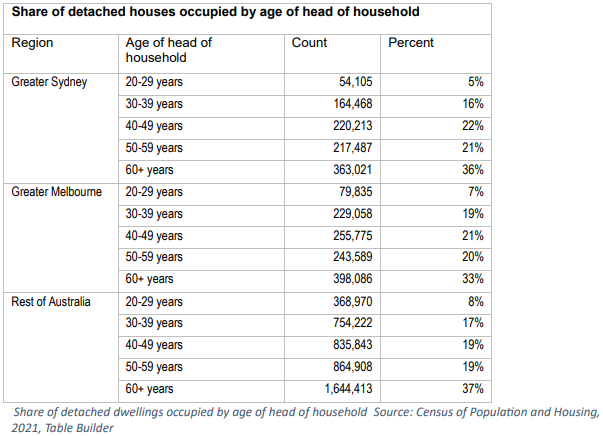

This competition is occurring at a time when just over half the detached housing stock in Sydney and Melbourne is held by household heads aged 50+. A remarkably small share of these households is exiting or downsizing, thus gumming up the supply of established houses.

In the case of high-rise apartments, developers cannot make a profit unless they target the high end of the apartment market.

What to do?

The key goal must be to restore the housing market to equilibrium. The factors contributing to the current crisis have been building up over many years. Therefore, resolving the crisis will take time, and will need investments and policies. These will transform the housing industry from small scale operators to larger companies that can operate with scale and improve productivity and leverage advanced manufacturing techniques to allow more pre-fabrication.

Solving the crisis will also need an adjustment to the current reliance on interest rates in managing inflation pressures.

We also need to lift the level of thinking on our understanding of how people choose and use housing, in particular, understanding the typical flows that occur through different types of housing stock at different life stages. When a housing market is in equilibrium this can help planners to identify ‘stuck’ market sectors and to shape policies to improve normal flow.

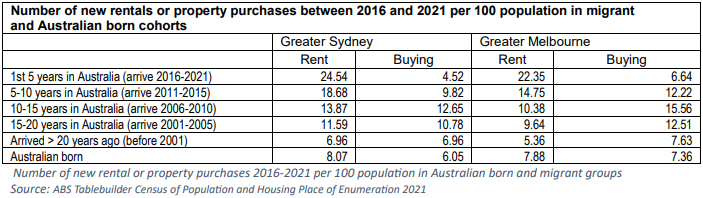

In the short term, the only realistic strategy likely to soften the rental crisis is a slowdown in the immigration influx. This is because recently arrived migrants are the main source of new rental demand in both Sydney and Melbourne.

Some industry and government sources argue that any such curb would be counter-productive because migrant tradies are needed to build the extra dwellings. We show that this belief is wrong. Few migrant tradies are currently being visaed. This will not change because Australia’s construction trade qualification system will not allow it. The focus must be on domestic training.

Slowing immigration, at least in the short term, will not solve the first homeowner crisis. Relatively few recently arrived migrants have the resources to compete in the detached housing markets of Sydney and Melbourne. However, they can and do compete successfully a decade or so after arrival. We show that those arriving before 2016 are currently the biggest source of demand in these markets and they dominate the ranks of buyers in the fringe suburbs of Melbourne.

Even if migration stops, the impact of this lagged demand will be felt for years. The huge wedge of migrants locating over the years 2022, 2023 (and probably 2024) will give an unprecedented push to this demand.

The only realistic medium-term option that can significantly provide for this need is to open up the respective city fringes for detached housing. This can be delivered at a fraction of the cost of medium and high-density housing in the middle and inner suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne. It is not being vi utilized because of deliberate policy decisions by the Victorian and New South Wales Government to restrict outer suburban expansion.

Though fringe developers, needless to say, agree with this stance, they face almost uniform opposition from State Governments, housing experts and commentators. One exception is Alan Kohler who, in his recent Quarterly Essay, reached the same conclusion as we do, if by a slightly different route.2

Therefore, the strategies to fix the housing crisis need to cover all the levers that can be applied – opening the fringe, new industry policy, reducing migration levels, improved workforce training, changes to monetary policy, new transport links, innovation in construction techniques and adoption of advanced manufacturing methods – all these factors have a role to play in restoring our housing system to equilibrium.

Recommendations

At the outset, we highlighted the likelihood of the housing crisis both worsening and also lasting longer when policy makers take a narrow lens to the problem. It will also worsen when recommendations are made based on an incomplete and inadequate understanding of the housing market.

To build a sound evidence base for proposed policy initiatives the first step is to build an understanding of the current situation. This requires thinking about housing as a system with interconnected parts, and to develop nuanced thinking. For example, buyers are not a single group – the options available to buyers, the preferred type of housing and location vary across first home buyers, upgraders, re-locaters and downsizers.

The second step is to work out, at a system level, what we want our future to look like. The system in focus here needs to be the overall dynamics of the housing market, not specific arbitrary benchmarks. We suggest a goal for the future of the housing market in Australia is a system that is close to equilibrium, with home prices rising each year, but below inflation. This would slowly improve housing affordability and avoid the economic calamity that would arise from a severe collapse in home prices.

The third step is to put forward hypotheses as to how we can move towards our broad goal. We believe that initiatives must address issues of both demand (across all market segments) and supply (including workforce, productivity improvements and capacity), as well as macro-economic policy settings and regulatory settings.

We have prepared a number of recommendations to tackle the crisis gripping Melbourne and Sydney, which can help restore housing affordability and equilibrium to the housing market.

Recommendation 1 – Stop adding fuel to the fire.

We have highlighted the long-term nature of the problems of housing affordability, including the fact that the majority of housing demand over the next 10-15 years is already locked in through the lag effect of migration.

Actions are required now to give the housing system a chance to return to equilibrium in the future. This means that net overseas migration (NOM) must be reduced very significantly. While it will take around 10 years for the impact of recent levels of high migration to wash through the system, significantly lower levels of NOM will reduce short term pressure on rental markets and allow the housing market to reach equilibrium in the longer term.

Recommendation 2 – Recognise the impact of the migration lag effect and fast track urban fringe development.

The scale of the housing crisis is such that ‘the least worst’ option to improve supply of affordable house and land options is to allow increased urban development on the city fringe.

It is important to recognise that a significant component of the response to the housing shortages that followed the return of servicemen after WW2 and high levels of European migration was relatively unrestricted development on the city fringe.

There is a need for State governments to commit to increased investment in infrastructure in the fringe The goal should be that 50% or more of new builds will take place on the fringe, until we approach equilibrium in the housing market.

Fringe development is not ideal, however not doing this now will make the housing crisis worse for many years longer.

This will require ditching the dominant ‘up not out’ policies of the NSW and Victorian Governments. It must include opening up the precinct planning system so that new developments can proceed much quicker than is presently the case. Also, there will have to be a commitment to increased government investment in infrastructure in the fringe.

Recommendation 3 – Increase the capacity of the non-unionised builders to construct multiple medium density developments simultaneously

Recognising the small builder is typically the most productive provider of housing (producing housing at substantially lower cost than large builders with unionised workforces), they need to be supported with improved access to capital to fund multiple jobs simultaneously to accelerate the number of dwelling units that can be completed each year.

Recommendation 4 – Explore the opportunities to increase productivity in the sector through investment in advanced manufacturing that can prefabricate modules, reducing the need for skilled labour on building sites.

Government R&D funding and programs can focus on technology to reduce time, cost and material wastage in construction. This funding can not only improve housing outcomes but also develop expertise that can be sold around the world.

Recommendation 5 – Reduce the transaction costs and increase local downsize options for empty nesters to make the choice to downsize from a detached dwelling to a townhouse or other medium density development across middle ring suburbs.

Importantly, this means a decentralised approach for encouraging town house and low-rise flats and apartments, rather than clustering them into specific precincts that suit planners but not the prospective buyers.

Recommendation 6 – Improve transport links between the capital cities and major regional cities so that upgraders have an extended choice of areas in which to purchase, reducing asset inflation pressures on high amenity detached dwelling stock.

Recommendation 7 – Reduce reliance on the blunt instrument of interest rate management to control inflation.

Give the Reserve Bank the power to vary the GST rate within a pre-set range. This will allow both interest rates and GST to be used as tools to manage the levels of economic activity and spread the impact of these controls across the community, rather than hitting home buyers only. With less distortion of the capital market the costs for developers in building new homes is reduced.

1 Calculated from Table 3 in J. Phillipa and J. Simon Davies, Migration: A Quick Guide to the Statistics, Parliament of Australia, January 2017

2 Alan Kohler, The Great Divide, Quarterly Essay No. 92

David McCloskey is CEO of Mimesis Labs, a digital technology business, and a Research Associate of the School of Media, Film and Journalism ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision Making + Society at Monash University and is a member of the Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI).

Bob Birrell (PhD Princeton – Sociology) was the founding director of the Centre for Population and Urban Research at Monash University and is currently the head of the Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI), an independent think tank on population and related issues.