This is an edited extract from an address given to the National Press Club by Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz, chair of the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council on September 4 2024.

Our housing system is simply not working. Prices and rents are growing significantly faster than wages, 170,000 households are on public housing waiting lists and over 120,000 people are experiencing homelessness.

The pressure on households is considerable. Since January 2020, house prices have risen by over 30% in capital cities and over 50% in regional areas. The median house price has reached 7.7 times median household income, close to historic highs. Since interest rates started to rise, repayments for borrowers have increased by as much as 60%.

Home ownership rates are falling, particularly for younger households. In 2001, the year my daughter was born, 51% of 24-to-35-year-olds owned their home. Today, just 43% do. She’s now 24 and we can clearly see the challenges presented to her generation in terms of accessing home ownership where there isn’t housing wealth to pass on.

Renting is no easier. Renters in the private market have experienced a sharp rise in rents of almost 40% since January 2020. Paying the rent now consumes a record 32% of household income on average. Imagine the stress, maybe you’re experiencing it yourself, of coping with the rising cost of living and wondering where the rent is going to come from.

Housing is important to everyone, to our families and our children. It is clear that the community, including government, now recognises that this is one of the most important issues of our time and that we all have a role to play. It is puzzling to me why, given the acute situation we are in, that we don’t prioritise the housing system more than we do.

Let’s unpack some of the causes of this crisis, the outlook for the next five years, and explore five areas that can take us forward.

Causes of the current crisis

The Council recently released our first State of the Housing System Report, and as you would expect, it paints a grim picture, driven by long term structural and cyclical factors. Beneath the ebbs and flows of cyclical challenges there are numerous entrenched structural constraints that limit housing supply and reduce affordability. I’m going to briefly call out just seven.

Source: National Housing Supply and Affordability Council

There is a limited supply of suitable land for housing. Where land is available, sites can be highly fragmented or have limited enabling infrastructure, such as water, sewerage, power, roads and rail connections, or suffer from restrictions that limit the optimal use of land.

Our planning approval systems are too complex and too slow. Arrangements vary across states and territories and across the more than 500 local governments that provide planning consent authority. The frameworks and processes that dictate what gets built, and where, are hugely biased against change.

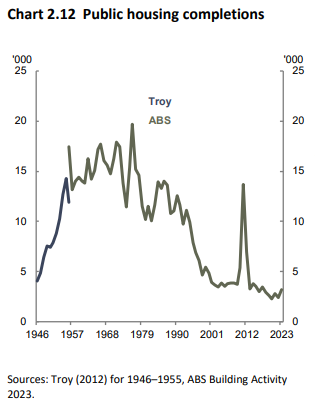

We have under invested in social housing. Social housing as a proportion of all housing has fallen over recent decades, while demand has soared – wait lists for greatest need households are up 52% since 2018. Given Australia’s remarkable and unparalleled record of 31 years of economic growth with only one short COVID induced recession, how can that be a fair and just outcome for our country?

Source: National Housing Supply and Affordability Council

How we finance new homes is a major constraint. We rely on households to provide financing for new homes through off-the-plan pre-sales, or committed construction contracts, and we put plenty of barriers in the way of foreign investment. Both of these serve to reduce the sector’s capacity to respond quickly with supply to meet demand.

Various features of our housing system, notably stamp duty, mean that we don’t use the housing stock we already have as efficiently as possible. Almost 4 million dwellings had 2 or more spare bedrooms on the night of the 2021 Census. And the growth of the short-term rental market through platforms such as Airbnb and Stayz has removed existing stock from the long term rental market.

We’ve had decades of weak or even negative productivity growth in the construction sector, reflecting the fragmented nature of the sector and low levels of innovation. The ABS estimates that Australia’s construction labour productivity rose by just 0.2% per annum in the 30 years to 2023, compared to 1.3 per cent in manufacturing. Since 2014, construction productivity has been on a downwards trend.

Even if we solved all the other problems, we don’t have enough construction capacity to deliver the homes we need. Cost increases have led to an elevated level of insolvencies in the sector. The construction workforce is ageing, and of those that do enter apprenticeship training, only half complete their course. There is also significant competition for labour coming from major infrastructure builds in New South Wales and Victoria, and from the resources sector in Western Australia and Queensland.

Put all those factors together, and the stage is set for housing affordability to deteriorate further over the next few years, and this from already challenging levels. Under current policy settings, we are likely to fall 260,000 dwellings short of the target of 1.2 million new homes within five years. Both rents and house prices are forecast to continue to outpace inflation over the next several years.

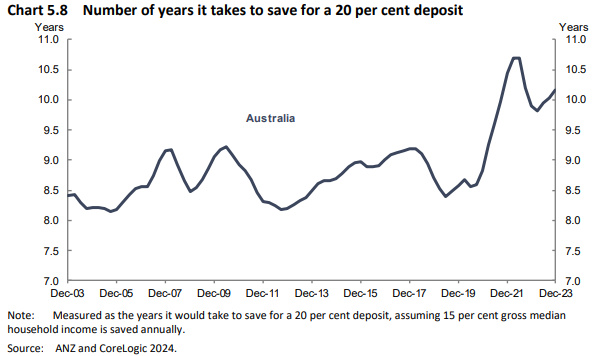

The median income household now needs around 10 years to save the deposit for the median home. More alarmingly, even those median income households who can raise a 20% deposit could only afford 13% of the homes sold in 2022–23 due to mortgage serviceability. Lowest income households could afford only one per cent of homes sold.

Source: National Housing Supply and Affordability Council

Australia deserves a better housing system. It’s an economic and social imperative in so many ways. Given the significance of the challenges we’ve been discussing today, it would be easy to despair, but I prefer to think of it as a call to action that requires bold measures and innovative solutions.

Let me highlight five areas that require immediate focus to move us towards that better housing system.

Five areas that require immediate focus

Firstly, we need to have adequate investment in social housing. Investing in social and affordable housing, whether that’s by government directly, or by the for purpose and private sectors, makes good economic sense, especially where it offers good access to employment and amenity.

It alleviates the insecurity associated with private rental housing. It reduces homelessness and the incidence of poverty, which in turn generates savings for all taxpayers. In fact, SGS economics estimates that for every dollar invested to bring about the supply of social and affordable housing, the Australian community saves $2.

Ongoing and predictable investment in social and affordable housing also provides a stable base level of construction activity, which reduces the challenges that arise from an inherently cyclical sector.

Secondly, we must commit to best practice zoning and planning systems across the country. We need to remove politics from the assessment process, digitise our systems, and move towards performance-based systems and away from open discretion.

Thirdly, we need to build more capacity in the construction sector. The key to this is encouraging more workers into the sector including through support for training, and skilled migration channels. Government can partner with industry to promote trade careers and attract more people from under-represented demographics, including women and migrant workers.

We should focus on upskilling the construction industry in advanced technologies and processes. This could be supported by increased use of advanced manufacturing techniques in social housing projects and other government procurement and accommodating innovation in building codes and regulations.

Fourthly, we need a better system for renters. More than 30% of Australians rent their home. The number of renters is increasing, and those who are renting are doing so for longer. Renting is the only viable option for an increasing share of the population.

But in many ways our system does not work for renters. Housing quality and maintenance are variable – ranging from excellent to utterly inadequate. Security of tenure can be fragile. We need regulatory frameworks that better support renters.

This could include things such as having a nationally consistent policy regarding reasonable grounds for eviction, no more than one rent increase per year and requiring minimum standards for rental property. The Council does not support rent freezes. They only serve to inhibit supply – the very thing we are trying to have more of.

More institutional investment in housing – known as build-to-rent – would benefit both investors and tenants. Institutional investors need long-term assets with stable income streams, particularly if those assets are less well correlated with other large, well established asset classes.

Institutional investment can drive innovation in design and construction, as well as efficiencies in energy consumption and maintenance. For renters, build-to-rent could improve affordability through increased supply, improve security of tenure, the quality of rental housing and the provision of services.

Imagine having a rental home where you could inspect the property when it suits you rather than in the company of 20 other people in the 15 minutes that the real estate agent allows. Imagine you can live there as long as you like, the concierge knows your name and your pet’s name, you can paint the walls, and repairs are done by the onsite team with no inconvenience to you.

This doesn’t need to just be confined to the medium and high-end segments of the market. Vibrant, mature and at scale build-to-rent markets exist in other countries, notably the US, UK and Japan. But in Australia, the vast majority of rental housing is supplied by individual landlords.

In July last year, the Council released a report on Barriers to Institutional Investment in Housing. Why is it that our institutions invest in this asset class internationally, but not here? It’s largely a nascency problem.

Because there is virtually no market and no track record, institutions, rightly or wrongly, require a significant risk premium which makes the economics challenging. And because there is no market in which to buy and sell, institutions need to create these assets through development, bringing a whole different level of complexity, and an increase in time and capability required.

Fifthly, we need to work towards policy settings that are well coordinated across all levels of government. One of the challenges in our housing system is just how many parts of government are critical to the provision of housing – Commonwealth, states and territories and local governments. And within these levels of government, multiple departments and agencies.

“An Australia I’d really like to see in my lifetime”

As former RBA Governor Phil Lowe noted in his farewell address ‘the reason that Australia has some of the highest housing prices in the world is the outcome of the choices we have made as a society: choices about where we live, how we design our cities, and zone and regulate urban land, how we invest in and design transport systems and how we tax land and housing investment’.

I’ve tried to imagine a world in which we have done all the things we need to do to create a healthy housing market. An Australia in which adequate housing can be accessed by households on all budgets, where there is frictionless transition to appropriate housing that suits the different stages of life. Renting would no longer be a stressful and insecure experience. Generations of families would be able to find appropriate housing near each other, and lifelong community connections could be preserved.

Our health budgets could be spent on preventing poor outcomes rather than remedying the effects of housing insecurity. Our housing system would no longer fail many First Nations people. Those who work in our stores, educate our children, serve our coffee, protect us and look after us when we are sick could afford to live in the suburbs where they work, and our cities would be devoid of excessive commutes.

That’s an Australia that I would really like to see, and I’d really like to see it in my lifetime.

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz chairs the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council. The Council’s “State of the Housing System 2024” report can be accessed here.