Keeping Australia competitive in the world today is a never-ending challenge of adjustments, reform and emulating world best practice.

The period from 1983-2000 saw well overdue reforms in the areas of labour market regulation and IR; trade and protectionism; sensible deregulation of the finance industry; superannuation; taxation and surplus budgets, and many more initiatives. Both the ALP and Coalition governments played parts in that era.

But nothing much has happened since.

The three areas of most interest to business are parliamentary, taxation and labour market reforms. We will touch on all three.

1. Parliamentary reform

The issue is simple: we need a democratic government, and we don’t have one. We have an upper house (Senate) that is not democratically elected, given that 12 seats are given to each of the states and two to the territories, regardless of population. This enables smaller states, fringe parties and single-issue members to be elected who are not representative of the electorate. They have veto powers on any bill passed by the democratically elected governing chamber, being the House of Representatives.

As a result, the lower house, democratically elected to govern the nation, is too often held hostage by minorities in the upper house. In short, we do not really have a British Westminster system at work. Their upper house cannot veto lower house bills, only delay them.

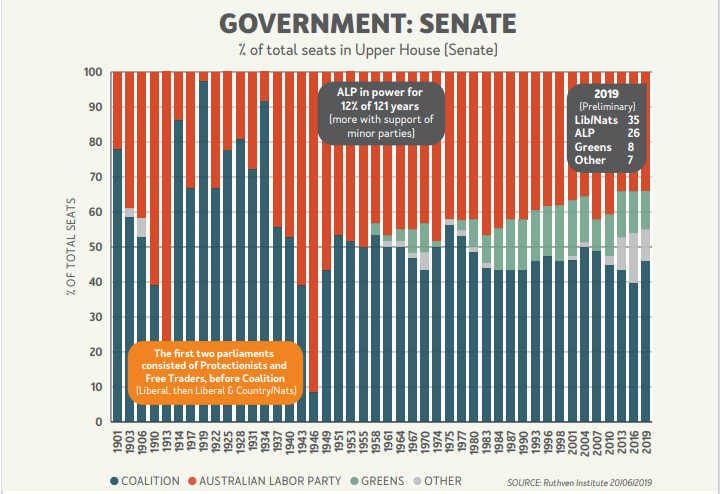

The chart below shows the undemocratically elected upper house, the ‘unrepresentative swill’ according to former Labor prime minister Paul Keating and the ‘feral’ chamber by another much-later PM. The Senate now controls Australia via its veto power.

As can be seen, this was not a problem for the first six or seven decades after Federation in 1901. While the Senate never fulfilled the role of protecting state interests—being a political-party chamber from the outset—at least it was dominated by the major parties. Fragmentation began in the second half of the 20th century, and special-interest minorities now make it impossible for either Labor or the Coalition to ever get a majority to implement their policies. We are now, no longer, a democracy.

This makes it near impossible to do the major reforms we need without them being rejected or watered down to be token and useless. As said earlier, there have been no meaningful reforms in the 21st century as a result.

We need to remove the veto power of the Senate (upper house) as in the UK, where their upper house (unelected House of Lords) can no longer veto a bill, only slow it down for a short period.

It will be difficult to change the veto power of the Senate, but it needs doing. It would require a long campaign over a year or two, driven by a competition-winning advertising agency that make the issues simple, needing of change and doable. A touch of humour or the ridiculous in the process wouldn’t go astray either; so Aussie.

2. Taxation reform

Wider tax reform is needed to help business be more internationally competitive, and for workers to be able to keep more of their wealth generation (wages) but be taxed more on their spending. In short, change the overall mix of taxes in the community to world best practice (WBP).

Australia is already one of the lowest taxed developed nations in the world at 28% of GDP versus the 35% OECD average. How long that should or could continue after our current GFC Mark II crisis as a result of our management or mismanagement of the economics of the COVID-19 is a matter of political choice.

This analysis looks at our mix of taxes, not the total impost.

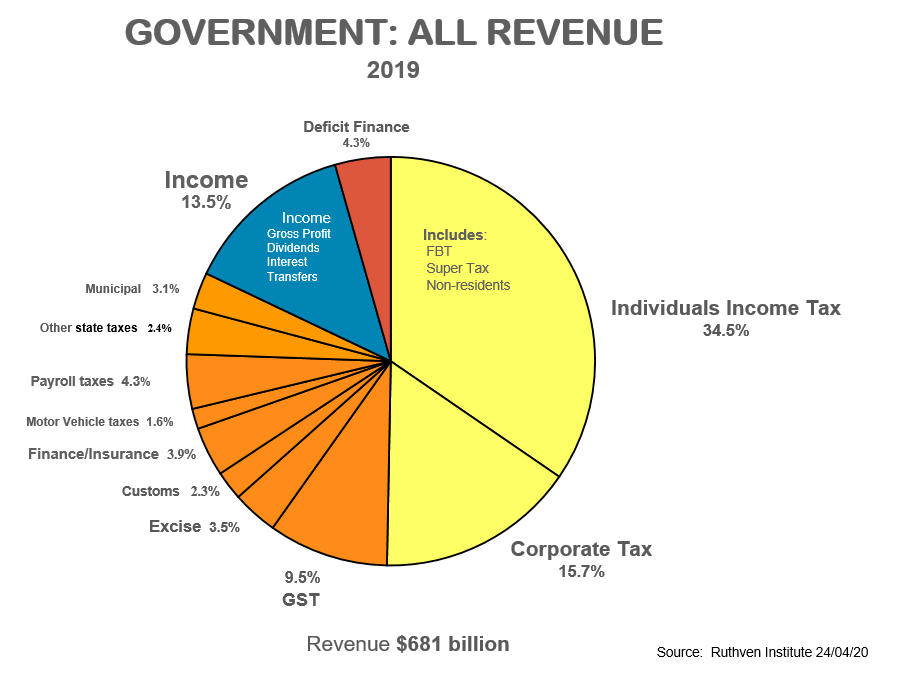

The chart below shows our current taxation mix plus other government revenue from Government Business Enterprises (GBES) and other investments, followed by a reformed mix of taxes to WBP standards of the components.

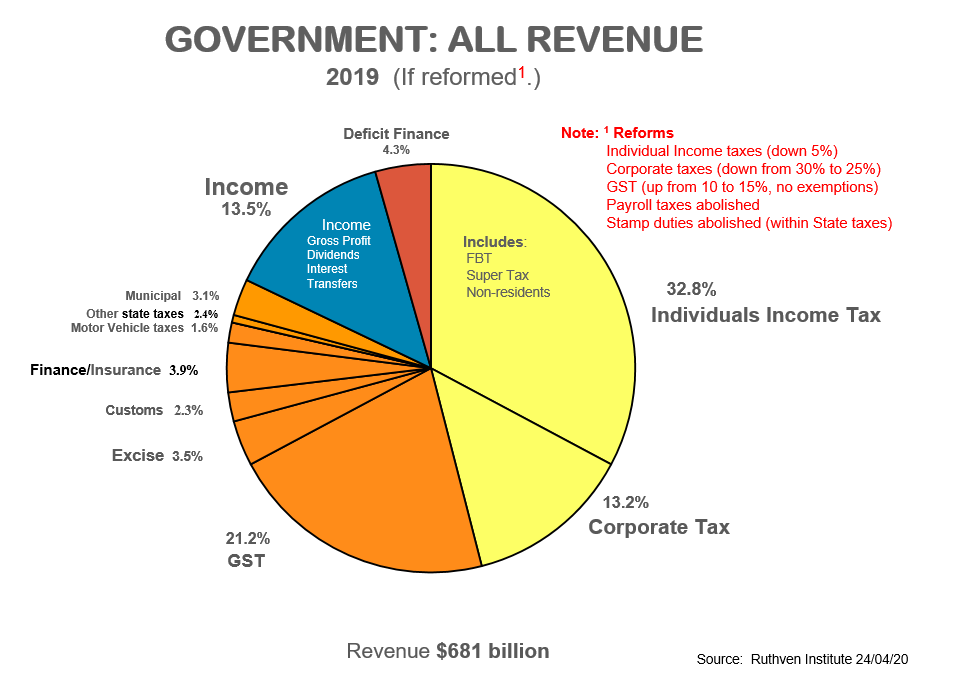

The next exhibit reflects the following changes (reforms):

- Individual taxes are reduced by 5%

- Corporate tax rate lowered from 30% to 25%

- GST has exemptions removed and the rate lifted from 10% to 15% (a la NZ)

- Payroll taxes abolished

- Stamp Duties abolished

The above mix becomes more in line with other advanced economies that have chosen to favour increasing expenditure taxes and decreasing income (wealth creation) taxes.

This is an area few governments have had the will to tackle, and simply don’t know how to sell it to the electorate. Reforms to our Senate are perhaps a precursor. If tax was tackled, perhaps again a competition-winning advertising agency could take on the logic, fairness and benefits of a new mix of taxes.

3. Labour market reform

Workers are on a new journey in the current Infotronics Age of services and Information and Communications Technology that displaced the Industrial Age of manufacturing and electricity in the mid-1960s, over half a century ago.

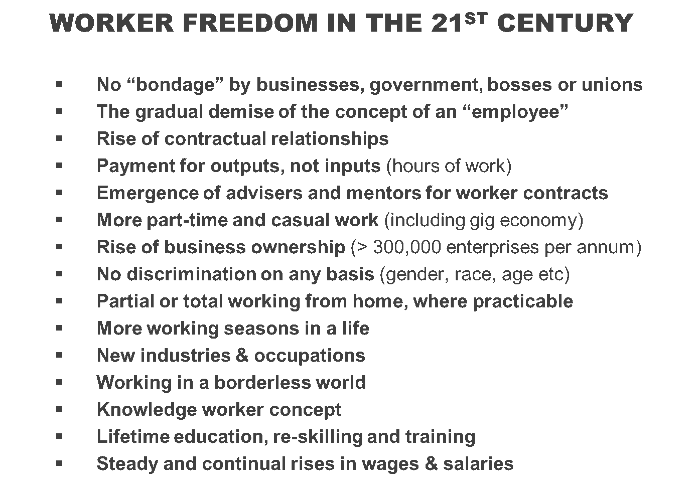

The characteristics of this journey as it involves employment are summarised below:

In essence, our new age is on a path to reduce subservience or ‘bondage’ of workers. This path is being resisted by unions and older generations, for control, habit or fear reasons. Less so with younger generations, especially the Millennials (under 38 years-of-age) and Generation Z (under 18 years-of-age).

Many factors are contributing to this preference for freedom:

- Casualisation, where part time and casual work provides more choices

- Average working hours shrinking from a 65-hour week (1800) to a 30-hour week (2020), allowing for two months’ leave each year, and increasing leisure

- The move to being rewarded for output rather than the rigidity of input (hours) regimes

- Lower cost of starting one’s own business (predominantly service businesses)

The fact that over 330,000 new business start-ups occurred in 2019 is a pointer to the pattern of taking charge of one’s own destiny when it comes to livelihood. This rate, representing 3% of households for many years, points to a preference for a B2B relationship by more and more workers over the industrial age B2E (business to employee) relationships.

Also, the churn rate of employees in corporations, around 8% a year, while not necessarily an indication of instability or dissatisfaction in each case, does point to the mobility of employment. More so in some industries than others.

It is just as hard for current governments to handle labour market reform, as other reforms, so productivity growth will be impeded for some years yet. And it is in poor shape currently.

So what?

There are encouraging promises made by Scott Morrison with regard to reforms on the Anzac weekend in April. He indicated all the reform studies and recommendations going back for many years will be taken off the shelves and out of the archives, dusted down, and used to establish a genuine reform programme.

This would be helped enormously if all parties to reform cooperated, including the federal government and the opposition, the states and the unions. One would think a post-pandemic environment should provide enough goodwill to see a large measure of this co-operation occur. But whether ideologies will give way to fundamental, rational and commonsense approaches to allow this to happen remains to be seen.

The near certainty is that without parliamentary reform to alter the veto power of the Senate, we could expect only watered down sub-optimal reforms.

We can but hope.

Phil Ruthven AO is Founder of the Ruthven Institute, Founder of IBISWorld and widely recognised as Australia’s leading futurist.