The older I get; the more accountability matters to me. Not that it didn't matter before – it did – but perhaps accountability feels rarer in today's fast-paced world?

In this article, I look to hold myself accountable by revisiting some of the topics I've written about over the last few years to see if what I said then still holds true today, or whether new information has come to light that's changed my perspective.

Baby bust: Australia's infertility problem

I first wrote about the worrying trends in global fertility rates in 2021. I'd recently read some of the amazing work that award-winning reproductive epidemiologist Dr Shanna Swan had published in this area, and it was frightening.

Swan’s research found that global sperm counts had dropped by approximately 1% per year, every year, for the past four decades. In total, sperm counts had slumped 40% in the 50 years to 2017. We’d also seen a 1% annual fall in testosterone levels and a 1% annual rise in miscarriages and testicular cancers.

So, what's the situation today? Well, the total fertility rate in Australia dropped as low as 1.59 births per woman in 2020. It has since recovered to 1.7 births, according to the latest statistics. But this is still far below the 2.1 figure required to sustain the population.

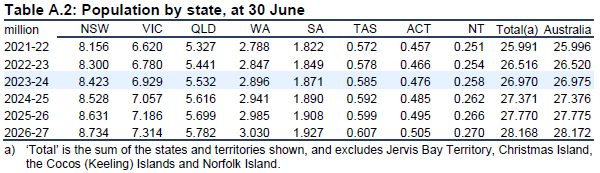

Australia’s population rose by 497,000 in calendar 2022, driven by a record net overseas migration of 387,000. As shown below, the Federal Budget forecasts Australia’s population will grow by 2.2 million people to 28.2 million by 2026-27, mainly driven by migration. The impact on housing, rents and house prices in the short term could be profound.

Source: 2023 Federal Budget

Nevertheless, taking a longer-term perspective, the 2022 Centre for Population Statement predicts the nation's annual population growth rate will not have recovered to pre-pandemic numbers within the next decade. Instead, it's predicted to fall gradually until at least 2033, slipping from 1.4% growth per year to 1.2%. This will take the population to 30 million by 2032/33.

In other words, while Australia's total population is predicted to rise over the next 10 years, the rate at which it is growing continues to slow down.

Globally, it's a similar story. Since 2020, Dr Swan has been busy keeping her research up to date, and what she's found isn't comforting.

Not only did she discover that sperm counts are falling rapidly in Africa, South America and Asia – regions that weren't well covered in her previous studies – but the pace at which they are declining worldwide is speeding up.

Her analysis shows that between 1972 and 2000, sperm counts were dropping by roughly 1.1% a year. From 2000 onwards, however, that rate has increased to 2.6% every year. Far from plateauing, the problem is getting worse, faster.

As a mother who recently gave birth to another baby boy, the data is upsetting. I would hate for my children to grow up in a world where they may struggle to raise a family. I'm sure every parent feels the same.

In South Korea, women are already having less than one child (0.89) on average during their lifetime. Replicate that on a global scale and the results are potentially devastating.

Many countries are now struggling to solve the problem of ageing populations. With fewer younger people to support older generations, we may see less innovation, poor economic growth, and a stagnation in living standards.

When I first covered fertility rates and ageing nations, I said there were many reasons to remain optimistic. In Australia, we have an excellent pension system, and I was confident that we could continue to drive growth, the economy and innovation.

While I hope that's still true, frankly, I was taken aback at how much worse Dr Swan's new data is. From an accountability perspective, perhaps I was wrong to be so optimistic in 2021, but it has nevertheless reinforced my belief that this remains a key issue that needs more focus.

The good news is that we now know some of the causes of the problem, so I'm still hopeful that solutions can be found.

The generation blame game: then and now

Generational theory was a topic that has fascinated me for a long time. I first learned about it nearly 10 years ago and have written several articles on the subject since.

Most recently, I talked about how the headlines were full of stories of generational conflict. If the media and politicians were to be believed, older and younger generations were constantly at each other's throats.

I admitted I was sceptical of that narrative. Delving a little deeper, contemporary research showed the generations were actually closer than ever before – figuratively and literally. Not only were more Australians living with their parents for longer, but the Bank of Mum and Dad was the country's fifth most popular lender.

Far from being at war, the various generations were offering each other support during difficult times. For example, two-thirds of grandparents were providing childcare to ease the burden on struggling family members.

I welcomed the news that different demographics were working together, especially with a huge generational wealth transfer on the horizon. Over-65s in Australia were predicted to pass down or spend an estimated AU$3 trillion between 2020 and 2040.

That was then, but what about now? Firstly, I think generational 'theory' has become a bit passe. While I was once a big fan, it all feels a bit dated now.

More often than not, it has seemed to drive a wedge between different age groups, rather than offer meaningful, actionable insights into people’s lives.

In fact, a year after my article was published, a major survey from the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) found that people are rejecting the concept of ‘generations’ entirely.

The vast majority of Australians don’t identify with labels such as ‘boomer’, ‘millennial’ or ‘Gen Z’. They view people as individuals with unique experiences and perspectives rather than pigeonholing them based on age.

I checked Google searches for the words ‘millennial’ and ‘boomer’ in Australia and found they peaked in November 2019, and have since mostly petered out.

One possibility is that the Covid-19 pandemic helped remind us all how much we appreciate our loved ones, whatever their age? Or perhaps we've grown out of blaming other generations for the problems we collectively face as a society?

Whatever the answer, I believe this is good news for the looming generational wealth transfer. The latest stats from the Productivity Commission echo my previous figures – around $3.5 trillion will change hands between the generations over the next two decades. By 2050, baby boomers will be handing down $224 billion a year in inheritance to millennials and Gen Z.

And parents are already helping their children today by contributing an average of $70,000 to their children's home deposits to help them get on the property ladder, with a third expecting to be never paid back.

Commenting on the AHRC report, Age Discrimination Commissioner Dr Kay Patterson said:

"Although antagonism between the generations is often seen as a given, I was struck by the warmth expressed by focus group participants towards members of age cohorts other than their own."

Final thoughts

Staying accountable is important. I believe there is tremendous value in revisiting our previous positions and examining them through a present-day lens.

Sometimes we're wrong, and it's crucial to own that. In hindsight, I think generational theory has had its day and I need to adjust my thinking there as the world has probably moved on. And the fertility crisis is perhaps even more serious than I originally gave it credit for.

Ultimately, the lessons we learn from being accountable to ourselves arm us with the information we need to better navigate the world. Isn't that worth getting things wrong every now and then?

Emma Davidson is Head of Corporate Affairs at London-based Staude Capital, manager of the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.