At least once a week, in every bank and non-bank across the country, pricing committees have their regular meetings. These discussions determine the rates and fees on every financial product in the market. Each meeting is presented with enough data to make Edward Snowden jealous. Market rates, competitor rates, product profitability, capital costs, liquidity costs, changes in regulations … it can go for hours. I have sat on the pricing committees of four banks and numerous non-banks, and while each has a different emphasis, they all have common elements. This article is a simple explanation of how they affect all borrowers and depositors.

Many bank executives spend their entire multi-decade careers specialising in product pricing, and over the years, it has become extremely complicated. Entire consultancy firms have built their fortunes on advising banks, and the complexity of capital allocation and liquidity management plays beautifully into their hands.

At the heart of the pricing process is a Funds Transfer Pricing System (FTPS). The FTPS is usually controlled in a central unit such as the bank’s Treasury. Every asset writing or deposit raising unit in the bank must negotiate its own relationship with the FTPS and Treasury. The basic rules are:

- all lending units borrow from the FTPS (or Treasury)

- all fund raising units deposit with the FTPS (or Treasury)

- Treasury manages the resulting interest rate mismatch and liquidity requirements centrally.

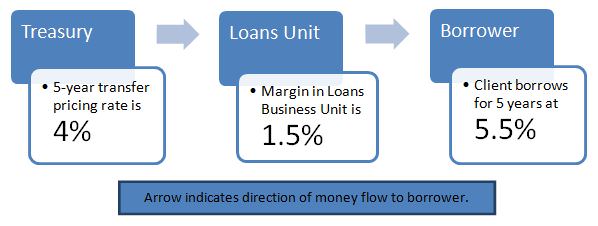

The FTPS allows the bank to isolate the performance of every business unit by measuring the margin between the FTPS rate and the customer rate. For example, on a five-year fixed rate loan:

By locking in the 1.5% margin, the lending business unit does not have to worry about interest rate mismatch or how to fund the loan. The transaction is combined with millions of others in the bank and the mismatch and funding is managed as one centralised risk position.

That’s the easy bit. Behind the scenes in the FTPS rate calculation, Treasury will ensure any capital or liquidity charges are passed to the relevant business unit. If a regulation changes, such as a requirement to hold more capital against a certain type of loan, the cost of business and the rate charged to the borrower rises.

Maturity transformation and pricing signals

One of the roles of banks is ‘maturity transformation’. Most borrowers want money for long terms (housing, plant and equipment, buildings) while depositors want access to money at short notice. Banks facilitate this by borrowing short and lending long, but it introduces risk into their balance sheet which events such as the GFC expose.

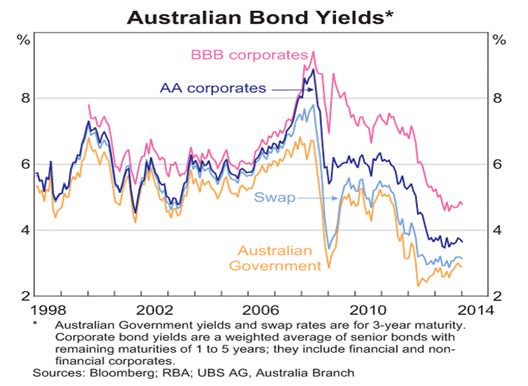

Regulators impose rules which control the extent of maturity mismatch or supporting capital required, and those rules have costs. Treasury will tweak the FTPS rates to recover the costs. For example, the new Basel III liquidity rules mean a deposit that may mature within 31 days must have high quality liquidity (essentially, government debt) held against it. Such liquidity usually carries an opportunity cost and as the table below shows, it is the lowest-yielding investment in the market.

Asset writers are generally charged for the capital they use. Each bank will estimate a different cost of capital, based on a variety of factors such as its view on how much capital it needs to hold to retain its credit rating, and the Prudential Standards for Capital Adequacy. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) grants approval for the more sophisticated banks, such as the Big Four, to use an internal ratings-based approach, using estimates of defaults and loss-given-default.

Every asset on- and off-balance sheet is given a risk weighting, and the lower the risk weight, the less the capital charge. It’s one reason why banks love residential mortgages: the risk weighting is low, and even in the simple models, a standard eligible mortgage with a Loan To Valuation ratio less than 60% is risk weighted at only 35% of its actual balance. Corporate loans can be rated 150%.

In response to changing regulations, banks adjust their pricing signals to encourage or discourage certain activities. For example, a product developed in response to pricing signals is the growth of Notice Accounts on deposits, where a higher rate is paid if the depositor agrees to a 32-day notice period. This avoids the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) charges imposed on short term deposits.

Obtaining the best rates from the bank

Although most customers are price takers, a knowledge of how FTPS works may give some negotiating edge in certain circumstances:

1. The less capital used on a loan, the lower the lending margin.

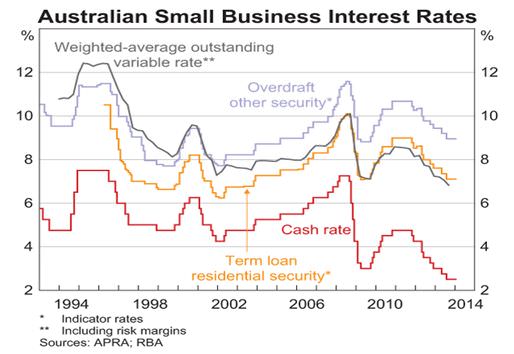

Housing loan rates are the lowest, and whatever the purpose, an offer of housing security can reduce costs. For example, borrowing on a margin loan to buy shares, even with the security of BHP and CBA shares and an LVR of 50%, will cost about 7%. A line of credit against the home is less than 6%, while mortgage rates are around 5%. Similarly, a small business that offers a residential property as security will achieve a lower rate, as shown below by the difference between the orange and blue/grey lines.

2. The classification of a deposit as ‘retail’, and therefore long-term and ‘sticky’, should achieve a higher deposit rate.

This issue has been discussed in Cuffelinks at length. A practical application is that a direct deposit with a bank into a retail deposit account will usually achieve a higher rate than a deposit with a super fund, as the fund itself is not considered ‘retail’.

3. The longer the maturity of a deposit, the more a bank is willing to pay above the swap rate.

Banks prefer the funding security of long term liabilities, and will generally pay higher margins above swap for longer maturities. In addition to the LCR mentioned above, APRA will be introducing a Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) calculation that will gradually influence FTPS rates. It is the equivalent of the 31 day LCR at the one year maturity. Banks will want to avoid maturities of deposits of less than one year and this will feed into better long term deposit rates.

4. Watch for early repayment interest costs.

Anyone borrowing for a fixed rate over a long term must understand how the bank may charge for early repayments. It’s far riskier than repaying a variable rate loan, and can easily be lost in the fine print. In my past life, I have briefed QCs and appeared as an expert witness in court disputes over the costs of prepayments of fixed rate loans. It can be a very messy business if market rates have fallen significantly since the loan was written.

As far as a bank’s Treasury is concerned on a fixed rate loan, the business unit has entered a long term contract to borrow money to lend to the client. If the loan is repaid early, Treasury will charge the business unit an interest adjustment if rates have fallen, and this will be passed on to the client.

How much? An easy way to estimate the possible cost is to multiply the estimated rate change by the number of years remaining on the loan. After one year on a five-year loan, if interest rates have fallen by 1%, the interest charge will be a little less than 4%. On a loan of $500,000, that’s $20,000. Many people think the simple act of repaying a loan early will result in some fees, but that’s not the main problem. I have seen early termination fees on large loans following the rapid rate falls in the 1990s run into millions of dollars.

The other tip is to make sure the documentation works both ways. That is, on a loan, if interest rates rise, then the payment should come to the borrower. It must be symmetric to be fair.

And the reverse of all this should apply for deposits.

Think about what is happening in the bank’s FTPS when you borrow or lend, and you may be able to improve your deal by taking advantage of each bank’s approach to pricing.