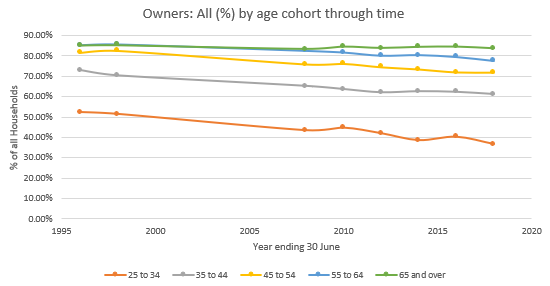

The Australian housing market is seen as increasingly unaffordable, potentially putting home ownership beyond the reach of ordinary Australians. Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show a declining trend of home ownership especially for the younger groups (see chart below). With 62% of Australians age 65 and over relying at least partially on the age pension (Age Pension - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (aihw.gov.au)), we ask: are you better off owning your home while on the age pension?

Source: Data from ABS 4130 charted by the authors

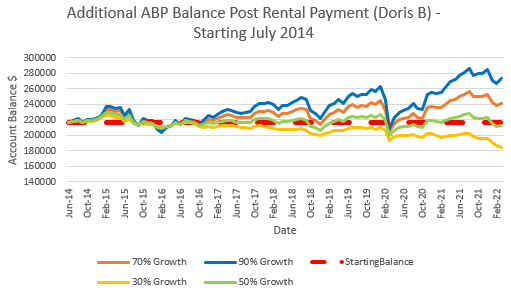

The extra asset test limit allowance for non-homeowners

The age pension asset test allows a certain amount of assets to be owned (excluding the principal residence for homeowners) before the full age pension rate tapers down to a partial pension. For non-homeowners, the asset test threshold is higher than for homeowners. Since March 2021, this extra asset allowance is $216,500 for those not owning a home, and is the same for both singles and couples.

A case study

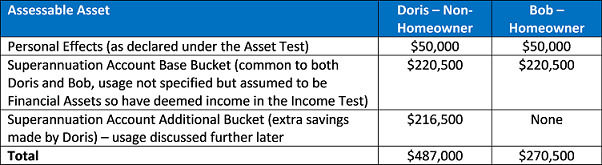

We explore the possible implication of this extra asset allowance with a case study of two hypothetical single retirees, both entering their retirement at age 67. Meet Doris, a renter, and Bob a homeowner. Doris could not afford to purchase a property during her working life but has saved more into her superannuation. Bob on the other hand, paid off his house in full by retirement age. We assume both start their retirement with the maximum assessable asset balance for full pension eligibility, given their homeownership status, like so:

We represent housing costs as the median cost of housing of renters with private landlords for Doris and homeowners without a mortgage for Bob (data from Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2017-18 financial year | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au)). As a renter receiving the age pension, Doris can also claim Rent Assistance (see Rent Assistance - Services Australia). As expected, Doris will have additional housing costs over Bob.

^This is the “People without Dependent Children” rate based on the Rent Assistance schedule

taken as of May 2022 from Services Australia.

How to fund rental costs?

Can Doris fund the extra housing costs of $10,862 p.a. with her additional superannuation savings of $216,500? We explore two hypothetical scenarios: Doris A buys an annuity, while Doris B invests this amount in an account-based pension (ABP).

Doris A - Annuity

The annuity that Doris A buys is an inflation-linked lifetime annuity which begins immediately. Indicative quotes from a market-leading Australian annuity provider suggests Doris A could receive approximately $10,654 per year inflation-adjusted (tax-free for an annuity bought with super money after age 60) for a purchase price today of $216,500 (Linearly interpolated for age 67 from quotes for a 65-year and a 70-year-old female, taken as of 16-May-2022. While annuity payment rates are not perfectly linear with age, it provides a reasonable approximation for this purpose).

While this covers almost all her additional housing costs shown above, the Income Test reduces her age pension to a partial pension estimated to be $23,044[1] p.a., lower than the full pension rate of $25,678 p.a. that Bob gets. Incorporating this reduced age pension payment, Doris A would still have a net housing cost gap of $2,842 per year compared to Bob.

Doris B – Account-Based Pension

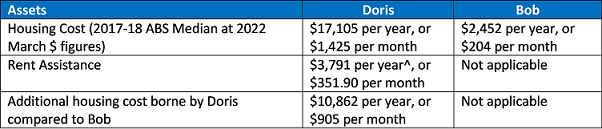

While annuity payment rates are fixed at time of purchase (albeit inflation-linked), an account-based pension will experience fluctuating returns. The key consideration for Doris B then is: what level of return, and therefore risk, does she need to take to fund her additional housing costs? We use APRA’s Simple Reference Portfolio (SRP) with tax-free investment earnings to represent ABP performance. The SRP was a benchmark devised by APRA for MySuper funds using a simplified set of assets. Due to the Income Test, Doris B will receive a pension of $23,637 p.a., or $2,041 less than Bob (partially offsetting the Rent Assistance), resulting in an additional housing cost of $12,903 p.a. over Bob. We simulate ABP performance at several growth allocations, with a starting balance of $216,500 and rental outgoings of $1075 per month ($12,903 p.a.), using historical SRP returns from July 2014 to Mar 2022 and adjusting the rent by historical CPI during this period[2].

If Doris B wanted to fully protect her nominal capital and pay her ongoing rental costs at the same time, she would have needed to invest at 70% or 90% growth allocations. We note these are higher than the 58% growth allocation reported for representative accounts in the retirement phase in the Australian Government’s Retirement Income Review (Retirement Income Review Final Report (treasury.gov.au). Risky investments involve a trade-off between return and volatility. The investor needs to accept this especially in Doris’s case who must pay rent. Lastly, historical returns are not indicative of future performance and any future market recoveries may not occur in the same timeframe as historical experiences. We acknowledge that Doris B has a difficult decision to make, one which is faced by many retirees.

Bequest and conclusion

We end the case study with consideration of these retirees’ estates, given their different circumstances.

Assuming Doris A lives past the withdrawal date of her annuity, on her death the annuity will have no withdrawal value and so will not contribute to her estate.

For Doris B, the estate contribution from her ABP will depend on how markets perform during the rest of her life. One risk to call out is that this ABP account may run out during her lifetime if markets underperform enough, especially if she leads a long life. She would then be forced to draw on her other assets or reduce her outgoings.

Bob, as the sole outright owner and resident of his home, intends to pass it to his estate.

When viewed solely in light of the extra asset test allowance for non-homeowners, this simple case study suggests it is better to be a homeowner rather than a renter. One caveat though is that Bob was assumed to be an outright homeowner; for a mortgaged retiree the conclusion may be different.

We caution that the above example is hypothetical and highly stylised to demonstrate the possible implications of the asset test limits and investment choices. The choices discussed were not intended to be optimal solutions. While the authors have made best attempts at understanding all the social security rules and benefits available, these are complex; therefore we acknowledge a possibility that there may be omissions. Nonetheless, it points out the challenges of retirement planning, especially as real personal circumstances will be much more complex. Readers should consider seeking professional advice regarding these matters.

Kirsten Wymer is Head of Risk Strategies and Research, and Edwin Lung is Head of Quantitative Analytics, at BT Investment Solutions (BTIS). The information provided in this article is general information only and it does not constitute any recommendation or advice. It does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Any taxation position described is a general statement and should only be used as a guide. It does not constitute tax advice and is based on current tax laws and our interpretation.

[1] All Age Pension payment amount estimates in this study come from Centrelink’s online calculator at Payment Finder - Services Australia (centrelink.gov.au). Estimates include all applicable supplements. Treatment of annuities under the Age Pension Asset and Income tests are discussed on this DSS webpage Means Test Rules for Lifetime Income Streams | Department of Social Services, Australian Government (dss.gov.au).

[2] For an ABP, its impact to the Age Pension will change as its balance varies due to market moves. But for simplicity and to illustrate the point, we are not looking at the changes in Age Pension eligibility through time in this simulation but focus on how it performs with a regular consumption stream under market volatility.