In Australia there is no universal pension as exists in, for example, New Zealand. The age pension is designed to support the basic living standards of older Australians. It's not a recognition of taxes paid previously, although this is a popular perception. It's to stop older Australians living below the poverty line.

It is a welfare payment that targets pensioners by applying a means test. The amount of age pension paid is determined by both an income test and an assets test. Both tests are used and the lower pension is the one adopted. Both tests apply a threshold and income or assets above those thresholds will reduce the pension.

This discussion will focus on the assets test because not all assets are assessed.

Assets test

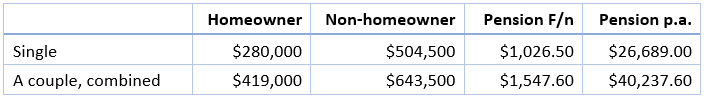

To receive the full pension, assets must not exceed:

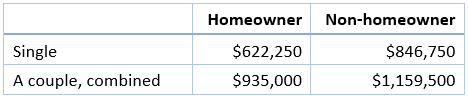

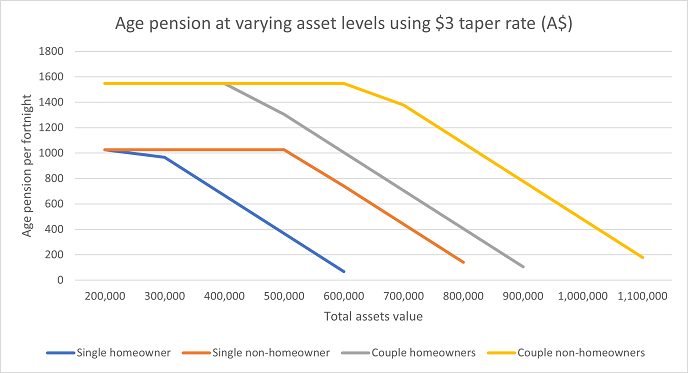

For both singles and couples, the pension is reduced by $3 per fortnight for every $1,000 over these thresholds. The part-pension is reduced to zero when assets reach:

The rate of pension reduction - or taper rate - of $3.00 per fortnight is $78 per year per $1,000 over the threshold, or 7.8%. An additional $100,000 invested at 6% will reduce the pension by $7,800 but investment income is increased by only $6,000 (ignoring any tax impact).

The reverse is also true. A reduction of $100,000 in assets will increase the pension by $7,800 but only $6,000 in investment income will be forfeited. Unless homeowner couple pensioners can earn at least 7.8% on their investments, they maximise their total income (pension plus investment income) by having no more than $419,000 in assets.

Instead of encouraging and rewarding saving and accumulating assets in retirement, this taper rate encourages the reverse.

Prior to 2017, the taper rate was $1.50 per fortnight or $39 per year per $1,000 over the threshold, or 3.9%. In that case, pensioners had no incentive to reduce assets because spending it would reduce both their pension income and the capital available to be liquidated over time.

Following a review, the government changed the taper rate as it was alarmed by the number of millionaires receiving a part-pension. The change disqualified about 300,000 people from a part-pension. To soften the blow, the government gave these people automatic access to the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card (CSHC) which provides almost equivalent benefits to the Pension Card.

The other sweetener was to increase the lower threshold, the point where the pension starts to decrease. That was increased as follows:

- Single: $209,000 to $250,000 which is now $280,000 through indexation

- Couple: $296,500 to $375,000 which is now $419,000 through indexation

Changes to this threshold made more people eligible for the full age pension.

The government seems reluctant to change this perverse taper rate because a less punitive taper rate would create another round of millionaires eligible for a part pension and that would impact the budget and enrage the media.

Investing in the family home may not be the best idea

Pensioners need to navigate the current taper rate which incentivises the reduction in assets to increase income. The fact that the family home is exempt from the assets test gives a strong incentive to overcapitalise the family home by renovating or upsizing in order to maximise the pension.

There are some who advocate this strategy. They aim to have no more than the permissible amount in assets that ensures they receive the full pension with all remaining capital invested in the tax-free family home. According to this view, retirees would be better off financially by becoming pensioners using the taxpayer's money.

This strategy for self-impoverishment is short-sighted.

With the assets test, the only thing not counted is the family home. Everything else is assessed including house contents, the car, caravan and bank balances. To receive the full pension, a homeowner couple can have $419,000 in assets. If fully invested, they can earn 6% on say $400,000 or $24,000 on top of their pension of $40,000 or about $64,000 together. Many would consider that to be a comfortable retirement income.

The first problem with this strategy is there can be no spare cash for the next car, holiday or roof repair because it’s all invested. Any spare cash in the bank will be assessed under the assets test and will not earn 6%. And, if some of this capital is spent, investment income is reduced without any compensating increase in the pension which is already at the maximum. There is also little capacity to rebuild those assets by returning to work.

Secondly, these pensioners then need to deal with Centrelink on a fortnightly basis and this means a loss of privacy and being subject to strict gifting rules. Such frequent Centrelink contact is not a pleasant experience.

Thirdly, because they are then totally dependent on Centrelink, these pensioners are as exposed to legislative risk as superannuants. The pension rules could change and they would have only limited capacity to respond unless they sell the family home, and that has its own complications.

By contrast, consider the couple who have $900,000 in assets. Using the same investment return, their income is $54,000 plus a pension of $2,719.60, but they have $900,000 of capital available to draw upon as needs arise. In fact, they are in the enviable position, where they can spend $100,000 and while they forfeit $6,000 in investment income, they gain $7,800 in additional pension income.

Self-funded retirees are even better off. Not only do they have more assets, but they don’t need to deal with Centrelink. They have complete discretion over the disposal of their financial assets.

What about a wealthier couple?

Consider a couple who maximise their tax-free super pension accounts of (currently) $1.7 million dollars each, or $3.4 million together. That gives them a tax-free annual income, using the same investment return, of over $200,000. It is difficult to see why any rational couple would remove $3 million from their super fund to upsize the family home just to qualify for the full pension. Their income would fall from $200,000 to $64,000 and they would then need to answer to Centrelink for every change in their circumstances.

Of course, that calculation may be different for pensioners who only just miss out on the pension due to excess assets, but the motivation then is often simply to gain access to the Pension Card and not the minimal pension. Few realise the CSHC provides almost equivalent benefits for self-funded retirees and the eligibility rules have recently been relaxed.

Additional investment in the family home to maximise the age pension becomes a straitjacket. The age pension limits the assets available for investment and therefore investment income. In retirement, your lifestyle is defined by your income, not the size of your family home. Income provides choices in every sphere of life.

To voluntarily put yourself in that straitjacket, at the mercy of politicians and bureaucrats, comes at a high price in terms of reduced income, and loss of discretion over your own affairs. To do so just to receive a refund of your taxes seems ill-advised and injurious to a long and happy retirement.

Jon Kalkman is a former Director of the Australian Investors Association. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. This article is based on an understanding of the rules at the time of writing.