There’s been a lot written about how Australia is in the early throes of the biggest intergenerational wealth transfer in its history. Most of it has focused on the mechanics of the transfer, who’ll get the money, and when. Also, how financial advisers are licking their lips given the prospect of an increasing need for their services.

But there’s been less debate about whether the wealth transfer is a good thing for the country. I’m going to argue that it’s not.

It’s not bad because of the inheritances involved. And it’s certainly not bad because of the wealth involved. If you’ve managed to build a sizeable estate to pass on, that’s good for you.

What’s more problematic is the explosive asset growth, especially in housing, that’s accompanied the bequest boom. It’s the result of decades of poor Government policy and it’s creating a host of economic and social problems – some obvious, others less so.

What’s the intergenerational wealth transfer?

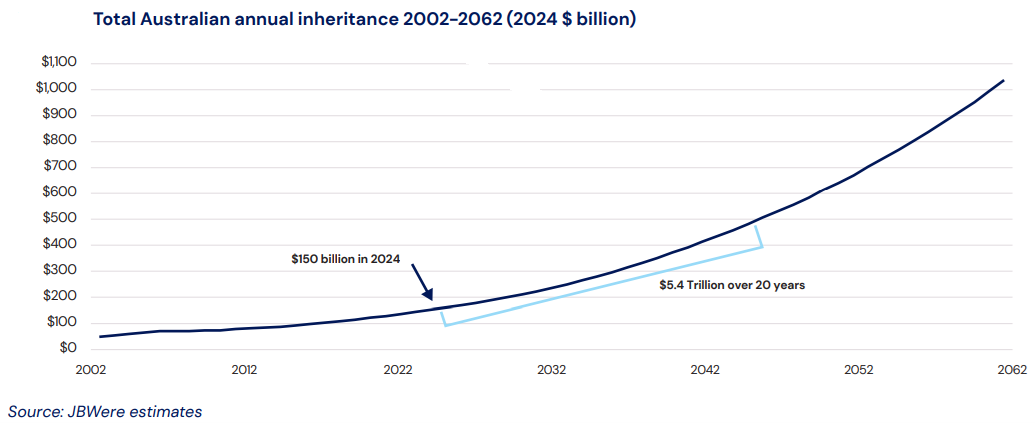

The issue gained prominence with the release of a 2021 Productivity Commission report which laid bare the extent of the coming wealth transfer. The report estimated that around $3.5 trillion in assets will be transferred in Australia by 2050. It said inherited assets would rise from the current $120 billion per annum to $500 billion per annum over the next 25 years. And that most of the assets would come in the form of superannuation and residential property.

Stockbroker JB Were has recently updated the Productivity Commission figures and suggests that the wealth transfer will now total about $5.4 trillion.

Stock trading firm, AUSIEX, has found that the wealth transfer is likely to happen sooner than expected. It suggests Baby Boomers are leaving the workforce at an accelerated pace, and they’ll be all but gone from workplaces by 2028:

“It doesn’t stop there. In 2027, the first of the baby boomers will reach their statistical age of death (81 years for men and 85 years for women).

Baby boomer superannuation balances will start to deflate out of the system through retirement consumption and then through disbursement via the inheritance process.”

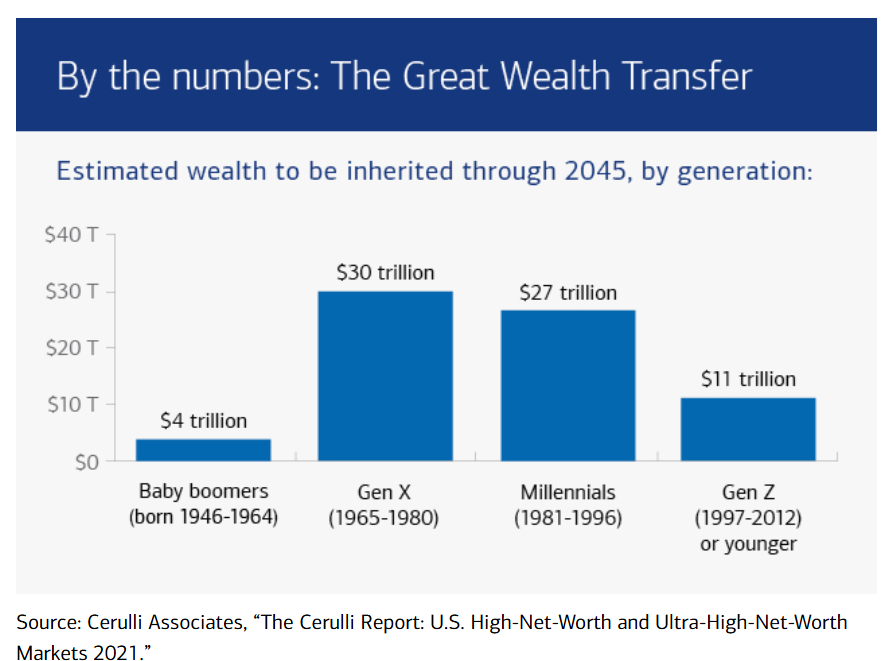

Not just an Australian issue

The inheritance boom isn’t just an Australian phenomenon. In the US, consultant, Cerulli Associates, estimates that US$84 trillion is going to be passed down from older Americans to millennial and Gen X heirs through 2045, with US$16 trillion of that set to be transferred within the next decade.

As a share of national output, French inheritances have doubled since the 1960s while in Germany, they’ve trebled. In Italy, inheritances now total around 15% of GDP.

The Kings Court Trust and Centre for Economics and Business Research forecasts that about £5.5 trillion will be passed down in the UK over the next 30 years.

Three key drivers

There are three factors behind the increasing inheritances:

1.Greater wealth. Since 1980, there’s been a massive asset boom. Shares have catapulted. Housing has exploded. Gold, Bitcoin, and art have also done well. Combined with low inflation, until recently, that’s been a boon for wealth both in Australia and globally.

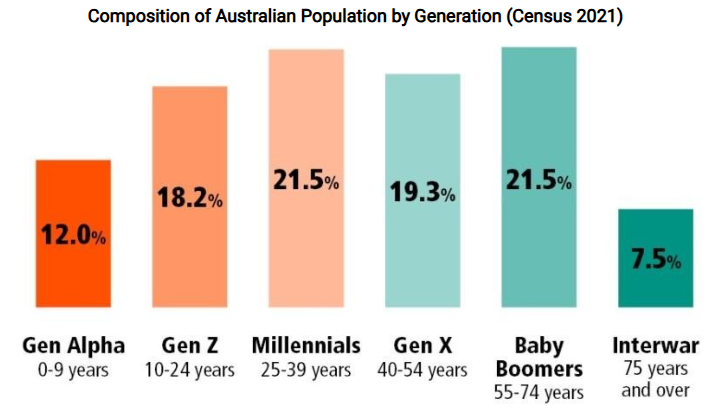

2.Demographics. A large cluster of Baby Boomers entered their prime during the early years of the asset bull market. Now the Boomers are mostly retired and passing on their wealth via gifts and inheritances.

Source: ABS

3.Low death taxes. Australia doesn’t have inheritance or estate taxes, while in the US and UK, so-called death duties when measured against Government tax revenues are near 100-year lows.

Consequences of the wealth transfer

The wealth transfer issue is especially acute in Australia given the extent of the asset boom that’s driven it. Specifically, the housing boom. Housing makes up about 56% of Australia’s total wealth, according to CoreLogic. And Baby Boomers have the highest levels of home ownership.

The 2021 census revealed that Boomers were 3 times more likely to own their home outright than Millennials were at the same age.

Put simply, the greatest wealth transfer in Australian history is largely the result of an extraordinary housing bubble that’s now into its fifth decade. That bubble, and the associated inheritance windfall, is leading to all sort of economic and social problems, including:

Low economic productivity. Productivity has barely budged in Australia over the past decade. That’s unsurprising given housing and super are many multiples greater in size than the economy. The money being tied up in these asset classes means there is less investment going to potentially more innovative and productive areas of the economy.

Greater inequality. Data from a recent HILDA survey shows that inequality has reached 20-year highs. Again, this isn’t a shock given rises in housing and super have far outstripped incomes and inflation. It’s also interesting how higher interest rates since 2022 have hurt the young more than the old, because the former hold a greater proportion of housing loans.

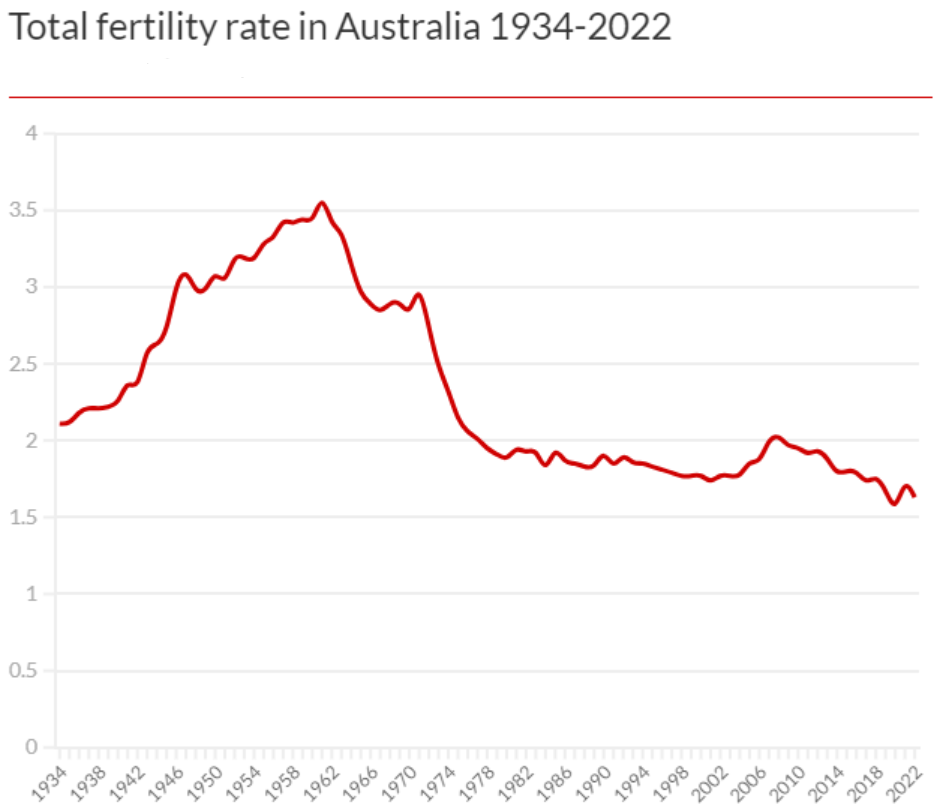

Lower fertility rate. Who can afford kids when affording a home is hard enough?

Source: ABS

Less mobility? The Productivity Commission has noted that wealthier parents tend to have wealthier children, even in the absence of wealth transfers. Inheritances strengthen this relationship — which means inheritances impede social mobility — because they move children closer to their respective parent’s position in the wealth distribution. This theory makes sense though it isn’t yet supported by any hard data in Australia.

Marrying in kind? Several overseas studies show that inheritances are becoming more important in explaining people’s choice of spouse. There is no comparable research in Australia to validate this.

The young taking on more risk? One thing that fascinates me is how younger people are taking on greater risk by putting money into speculative assets like meme stocks and Bitcoin. I suggest that this is partly tied to the asset boom. The young see the wealthy haven’t gotten rich by building a career and income. They’ve principally done it by owning assets which have appreciated in value.

Swings against major political parties. There is frustration by the growing gap in wealth between generations, and that’s spilling over into politics. In Australia, there’s been a swing against the major parties in favour of independents. In the US, they’ve voted in Trump. In Germany, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has become a major political force after recent elections. And that follows swings to far-right and far-left parties across many other European countries, including France.

The solution

The solution to the generational wealth gap and transfers would seem to be easy: increase taxes on superannuation or other forms of wealth and reintroduce a ‘death tax’ (we previously had one for a long time).

But raising taxes would just be a band-aid and an admission of failure; a failure to deal with the real issue causing most of the problems, namely housing.

To solve housing doesn’t require a genius. Significantly increase supply and remove all subsidies pumping up demand.

Until these things happen, we’re going to have continuing debates about the generational wealth gap and rise in inheritances.

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.