"For historians each event is unique. Economics, however, maintains that forces in society and nature behave in repetitive ways."

- Charles Kindleberger, Manias, Panics, and Crashes

It’s been around 20 years since I last read Kindleberger’s classic book. But with the 25th anniversary of the dot.com bubble last month (March 10), I thought I’d dust it off. We are, after all, in another bubbly environment. And while every bubble is unique in its form and duration, as Kindelberger notes, each has common characteristics.

To be honest, the book was a tougher read than I remember. I ended up skimming a lot of it. It was packed with every crisis, panic and mini-panic you could imagine, including the obscure Kipper und Wipperzeit episode.

This occurred just prior to the Thirty Years War, which broke out in 1618. It wasn’t a unique crisis. It was a story of currency debasement, a story as old as money itself.

This is what makes the book a powerful read. Each crisis is different, but at its core is the same range of human emotions. What you’re seeing today is just the latest episode of humanity mixed with a torrent of money.

While there is a huge amount of information crammed into Manias, Panics, and Crashes, the gold is in chapter two. It provides a framework for the rest of the book. Titled ‘Anatomy of a Typical Crisis’, it starts with the crisis model of the late Hyman Minsky. Kindleberger writes (with my emphasis):

"Although Minsky was a monetary theorist rather than an economic historian, his model lends itself effectively to the interpretation of economic and financial history ‘According to Minsky, events leading up to a crisis start with a ‘displacement’, some exogenous, outside shock to the macroeconomic system. The nature of this displacement varies from one speculative boom to another. It may be the outbreak or end of a war, a bumper harvest or crop failure, the widespread adoption of an invention with pervasive effects – canals, railroads, the automobile – some political event or surprising financial success, or a debt conversion that precipitously lowers interest rates.

But whatever the source of displacement, if it is sufficiently large and pervasive, it will alter the economic outlook by changing profit opportunities in at least one important sector of the economy.

If the new opportunities dominate those that lose, investment and production pick up. A boom is underway. ‘In Minsky’s model, the boom is fed by an expansion of bank credit that enlarges the total money supply."

Kindleberger’s book was originally published in 1978. At that time, the world of ‘tech’ didn’t really exist as we know it. Personal computers were only just being invented.

But in this era, the ‘widespread adoption of an invention with pervasive effects’ is all about technology. The internet was an example of a displacement. And we know how that turned out.

According to Kindleberger, "Each day’s events produce some changes in outlook, but few are significant enough to quality as displacements."

Displacement and euphoria

Artificial intelligence (AI) clearly qualifies as a modern-day displacement. You can see this in the charts below.

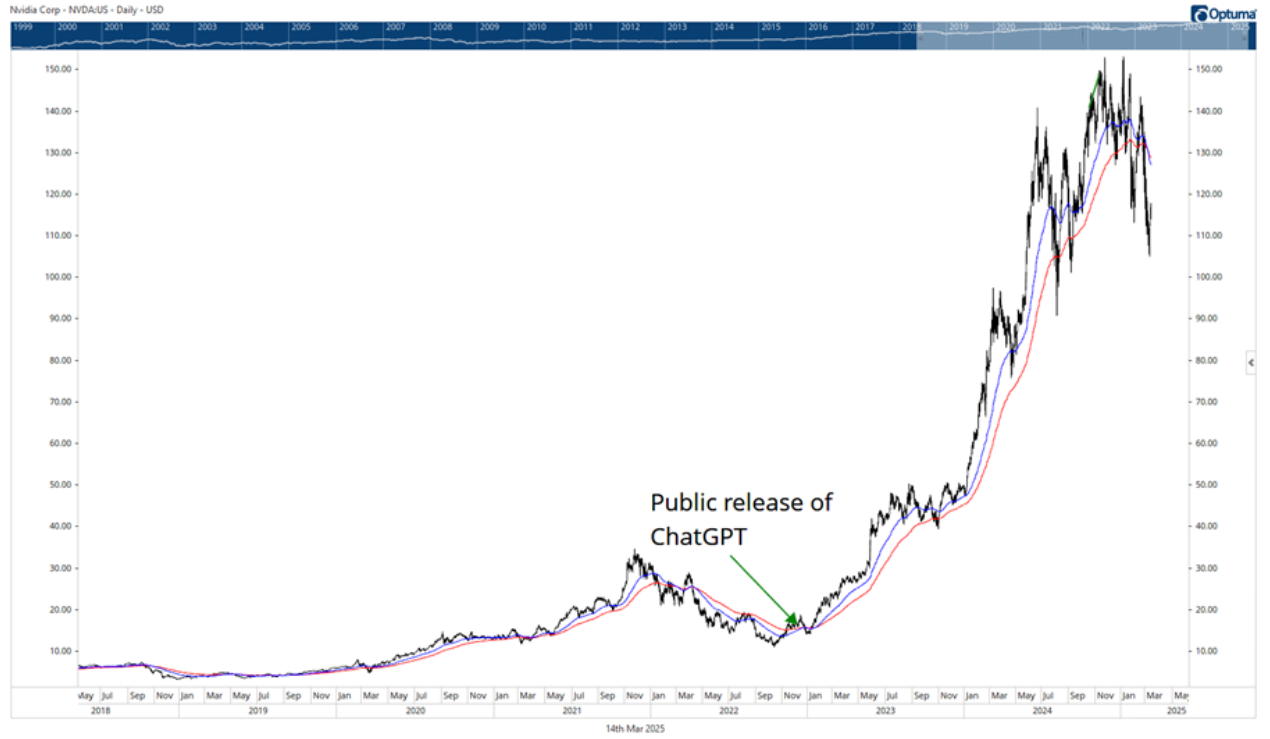

On 30 November 2022, ChatGPT came into the world. It was the first publicly available (and free) AI tool. It was the start of a mania. For evidence, look no further than Nvidia’s share price…

Figure 1: Nvidia share price chart. Source: Optuma

From the release date of ChatGPT to the recent peak, Nvidia’s share price soared by around 830%. In the previous year, Nvidia’s stock price had declined around 70% from the peak of the post-Covid monetary boom in late 2021.

ChatGPT, and AI in general, was the ‘displacement’ that stopped the bear market in its tracks. It allowed investor imagination to run wild.

Investment in chip technology and production ramped up…a boom got underway.

However, this boom didn’t follow the classic Minsky model. It wasn’t fuelled by an ‘expansion of bank credit’.

Not exactly, anyway.

As I’ll show you later in this article, the US Federal Reserve and Government, rather than private banks, provided ample liquidity to fuel the bubble.

Flush with cash from this liquidity surge and enjoying years of network effect dominance, the major tech companies went on an AI spending spree. Retained earnings and internal cashflows, rather than bank credit, fuelled this investment boom.

This is what makes this bubble unique. The huge investment in AI infrastructure didn’t come with destabilising bank debt. Therefore, the argument went, it wasn’t really a bubble. Moreover, the earnings were real. Therefore…again…not a bubble.

But one of the characteristics of bubbles and manias is the ability of investors to rationalise them at the time. As Kindleberger says, "forces in society and nature behave in repetitive ways". Somehow, this time is always different.

Historically, bubbles always have different characteristics. But at their core, they’re all the same.

When it’s a ‘widespread adoption of a new innovation’, like AI, the bubble represents a belief in something so new and profound that its possibilities and applications are endless.

In other words, the bubble is in investors’ imaginations. Because the innovation is unique and groundbreaking, its imagined benefits are unlimited.

It’s not just about Nvidia. You see it in the other ‘Magnificent 7’ stocks that are closely connected to AI too. Take a look at Meta…up around 560% at the peak from November 2022…

Figure 2: Meta share price. Source: Optuma

Or Microsoft, up 90% at the peak…

Figure 3: Microsoft share price. Source: Optuma

Or Alphabet aka Google…up 110%:

Figure 4: Alphabet share price. Source: Optuma

Or Amazon…up 160%:

Figure 5: Amazon share price. Source: Optuma

These are very large companies up significantly in just two years.

But, the argument goes, this isn’t a bubble because the earnings are there to support these higher prices.

But maybe the bubble is in the earnings? Maybe the displacement caused by the emergence of AI led to a one-off investment boom that has momentarily inflated a select group of companies’ earnings?

From 2022 to 2026 (forecast) Nvidia’s earnings per share are expected to increase more than 1000%. Meta’s by around 240%... Microsoft’s by more than 50%... Alphabet’s by 125%... And Amazon’s by around 550%.

Maybe these earnings are sustainable. But Kindleberger’s study of history and Minsky’s model suggest we need to be critical of such a view.

In Minsky’s model, euphoria follows displacement. While you haven’t seen euphoria in the broader market, you can certainly see it in the share price charts above.

You’ve also seen it in ‘quality’ stocks. This is the ‘sneaky bubble’ that joined the bubble in tech and AI. Costco Wholesale is just one example. This US$400 billion company trades on 50x earnings! Several Aussie stocks also benefited from this ‘quality’ premium.

Figure 6: Costco share price. Source: Optuma

Distress

But let’s get back to Kindleberger. After euphoria comes distress. Distress is brought about by changing expectations. Arguably, this is where we are now. Kindleberger writes (with my emphasis):

"Expectations in the real world may change slowly or rapidly, and different groups may wake up to the realization – sometimes at different rates and sometimes all at once – that the future will be different from the past. The period of distress may be drawn out over weeks, months, even years, or it may be concentrated into a few days. But a change in expectations from a state of confidence to one lacking confidence in the future is central."

I think it’s fair to say that the first quarter of 2025 can best be summarised by the term ‘changing expectations.’

There are two key events behind these changing expectations. The first is DeepSeek. This is the Chinese AI start-up that rivals ChatGPT and other Western LLM’s (large language models). It’s open-source and supposedly much cheaper run. Its release in January 2025 sent shockwaves through the industry.

Nvidia’s share price plunged 17% on the news. DeepSeek was the catalyst for changing expectations towards AI-related companies.

The election of Donald Trump is the other event behind ‘changing expectations’. This is more than just AI or tech-related.

The market initially welcomed Trump’s election. But it’s become clear he’s not bluffing with tariffs. His attempts to engineer a renaissance of the US manufacturing sector and restore jobs to the working and middle classes are spooking markets.

This is not the environment where one of the most expensive stock markets in history will thrive. The market, both here and in the US, has gone from a state of confidence at the start of the year to one of uncertainty now. As Kindleberger says, ‘a change in expectations from a state of confidence to one lacking confidence in the future is central.’

In his, or Minsky’s model, this change of expectations brings about a period of distress. Here again, Kindleberger’s study of history is instructive:

"Financial distress for an economy also has a prospective rather than an actual significance and implies financial adjustments or disturbances ahead. It is a lull before a possible storm, rather than the havoc in its wake."

He continues (with my emphasis)…

"Causes of distress are difficult to disentangle from symptoms, but they include demands on the capital market for cash when cash is tight, sharply rising interest rates in some segment or all of the capital market, balance of payments deficits, rising bankruptcies, the end of price increases in commodities, securities, land buildings, or whatever else may have been the object of speculation.

The end of a period of rising prices leads to distress if investors or speculators have become used to rising prices and the paper profits implicit in them. Of course, it is difficult—many would say impossible—to distinguish in advance a pause in a continued upward movement from a topping out that presages a downturn. Uncertainty on this score is itself a cause of distress."

Putting it all together

Okay…let’s back up a bit and put all this together.

We’ve had the displacement of AI and the release of ChatGPT in November 2022. It reversed a bear market and resulted in an extended period of euphoria.

However, the euphoria wasn’t widespread. It centred around tech and AI-related companies and industries, as well as ‘quality’ stocks. In a throwback to the ‘Nifty Fifty stocks of the 1970s, these are high-quality earners that investors believed you could pay any price for.

But the emergence of a Chinese AI competitor and the real Trump agenda have changed investor expectations. We’ve now moved into the distress stage. As Kindleberger states, ‘the period of distress may be drawn out over weeks, months, even years.’ History isn’t clear about how a period of ‘distress’ resolves itself.

Kindleberger writes:

"The essence of financial distress is loss of confidence. What comes next—a slow recovery of belief in the future as various aspects of the economy are corrected, a collapse of prices, panic, bank runs, or a rush to get out of illiquid assets and into money?

If there is no panic…financial distress may gradually subside."

And…

"When financial distress is followed by a crash or panic, there is no standard interval. It may be a matter of weeks or of years."

In other words, history is frustratingly vague about informing us as to what comes next.

Understanding this point is crucial. Otherwise, it’s easy to let confirmation bias take over. If you’re bearish, you’re going to expect panic and a crash. If you’re bullish, you’ll hope things resolve themselves without too much damage.

But understand…no one knows how this will play out. What we do know is that history tells us that we’re in a high-risk environment. We’ve had the displacement, the euphoria, and now, the distress.

Greg Canavan is the Editorial Director of Fat Tail Investment Research.