Volatility in financial markets happens when participants are faced with new information that runs counter to prior assumptions. This year, the mistaken assumption was inflation, which has proved far more problematic than central bankers and investors expected.

The gyrations across equity and fixed income asset classes in 2022 can be almost entirely traced back to inflation, interest rate levels, and expectations for each. This year, whether it was stocks or bonds, the longer the duration an asset had, the worse it performed. This is important to consider as we set return expectations looking ahead to 2023.

Peak inflation? Probably

In recent weeks, after markets were presented with data that pointed to a potential inflation peak, risk assets rallied, led by longer duration stocks and bonds. While only time will tell if we’ve hit the inflation high-water mark or not, the combination of base effects, the tightening pace of financial conditions, and rising recession odds will likely decelerate inflationary pressures in 2023.

However, not unlike how investors underestimated inflation, I believe they may be underestimating its impact on corporate profits. While falling inflation may prove beneficial for bonds, it could still prove problematic for profits and consequently stock prices.

Fading wealth effect, rising costs

As economies re-opened in 2021 and consumers were brimming with spending power due to government transfer payments, economic growth and corporate revenues skyrocketed, achieving double-digit growth rates.

Corporate revenues can be broken down into units and price. The number of units sold and at what price combine to produce revenues. Not only was unit growth strong, but more notable were prices paid, as evidenced by four-decade high inflation. While corporate input costs were rising, they were matched (or exceeded) by higher prices of goods and services sold, protecting profit margins.

During inflation booms, companies generally raise prices on the back of a positive wealth effect. Rising values for financial assets, used cars, homes, etc., combined in this episode with very high savings and rising wages, to generate significant pricing power for corporations. This cycle was typical for a high inflation period. However, what is also typical is what happens when inflation recedes.

Pricing power during inflationary booms, like the one we just experienced, tend to be ephemeral. For pricing power to be sustained, it must be accompanied by value-add. And that hasn’t occurred over the past year.

As the wealth effect fades due to falling financial asset prices and increasing investor anxiety, consumer behavior changes. And we have already seen signs of it. This earnings season, operating results from some US retailers show that consumers have begun trading down and prioritizing necessities, such as food, over non-essentials. Inflation usually peaks when consumers’ capacity to spend cannot meet the price at the checkout counter.

Falling inflation may potentially lead to higher equity multiples because long-term interest rates may have peaked (and that is good for long duration bonds). Though in my view, investors are underappreciating the drag on profits from falling prices.

Will history repeat?

Profits are a function of revenues and costs. While revenues are likely to decelerate with the economy and inflation, costs typically don’t recede as quickly and the earnings cycle ends. We believe history will repeat, and here’s why:

- While some companies have announced job cuts, most notably in the technology sector where customer demand is softening, there remains an overall labor shortage combined with a skills mismatch between available workers and the high-skilled jobs that remain unfilled. This should result in sustained elevated labor costs.

- The second cost input is capital. Following the global financial crisis, central banks made sure capital was both abundant and cheap. While inflation may recede some, it's not likely to fall to pre-covid levels due to structural dynamics at play such as an aging population with more consumers and fewer producers and significant increased capital investment by businesses seeking to decarbonize.

- While inflation and revenues are likely to recede in 2023, they will do so at speeds much faster than input costs. The result will be a lower profit margin regime than the all-time highs observed over the past several years and I don’t think this is yet reflected in asset prices.

Unrealistic expectations

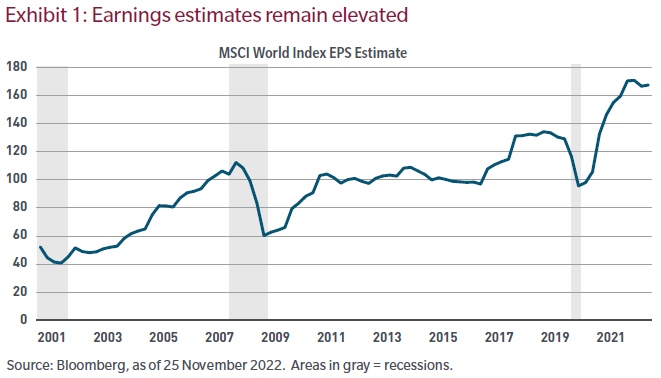

Exhibit 1 shows analysts’ global earnings expectations over the past several decades. Historically, in recessionary periods, profit margins plummet. But as the data show, analysts’ earnings estimates have slipped, but not by much.

The reasons, I suspect, are simple. Analysts tend to follow corporate guidance. And while companies are increasingly recognizing weakening end-demand, they’re also telling investors that they can reduce costs while sustaining historically high margins. But we have our doubts.

However, some companies will be able to sustain higher margins because they sell a good or service that’s highly valued by their customers. But the reality is that the majority will not. And those most at risk are companies with high and/or inflexible fixed costs and needing to increase capital expenditures to decarbonize amid a higher interest rate, falling inflation, weakening demand, environment.

What we expect for 2023

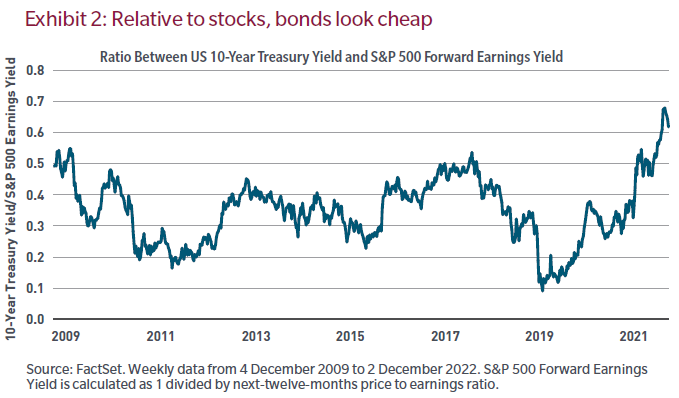

- While inflation should decelerate but remain elevated relative to the pre-pandemic period, the slowdown should prove a tailwind for select bonds, particularly high-quality sovereigns, municipalities and investment-grade issues. And relative to equities, bonds haven’t been this cheap in over a decade. The chart below illustrates the ratio between the yield offered by the US 10-year Treasury and the 12-month forward earnings yield on the S&P 500.

- Decelerating inflation is good for fixed income but will likely halt this earnings cycle and bring a long overdue profit margin reset. But not for all.

- Companies with uncompetitive products or services facing elevated capital costs and mandatory capital investments will be most at risk. Softer, but still relatively higher inflation compared with the post-GFC period will likely preclude financial bailouts and a return to unnaturally low interest rate regimes. These assets will become stranded.

- Conversely, while investors may find that even well-run companies have some, albeit small, level of margin reset, the opportunity to grow market share and take greater ownerships of profit pools will lead to even better operating performance over the long-term. The coming inflation slowdown and margin recession will create a new and positive earnings cycle for enterprises with a demonstrable value proposition and an ability to out-earn their natural cost of capital. And I am wildly excited about that.

Robert M. Almeida is a Global Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager at MFS Investment Management. This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to invest in any security or to adopt any investment strategy. Comments, opinions and analysis are rendered as of the date given and may change without notice due to market conditions and other factors. This article is issued in Australia by MFS International Australia Pty Ltd (ABN 68 607 579 537, AFSL 485343), a sponsor of Firstlinks.

For more articles and papers from MFS, please click here.

Unless otherwise indicated, logos and product and service names are trademarks of MFS® and its affiliates and may be registered in certain countries.