February is half-yearly reporting season in Australia. Overall it was positive, but there are problems lurking behind the headline numbers.

There are more than 2,200 companies listed on the ASX but the vast majority of them have never made a profit nor paid a dividend, and probably never will. Almost half of the total profits and dividends from the market come from just six companies – the four big banks plus miners BHP and RIO. A couple of dozen companies account for around two-thirds of aggregate profits and dividends.

Hot stocks irrelevant for overall market

Although most of the attention in the media is on the ‘hot stocks’ du jour - like Domino’s Pizza, Wisetech, Appin, Afterpay, Lynas - they have virtually no impact on the overall market. Even if they suddenly doubled or trebled their profits, or if they had a miraculous 1,000% increase in profits (most make losses – that’s why they are ‘hot’ stocks). What happens outside the top couple of dozen stocks in Australia has virtually no impact on the market as a whole, but that’s where speculators hope to strike it rich.

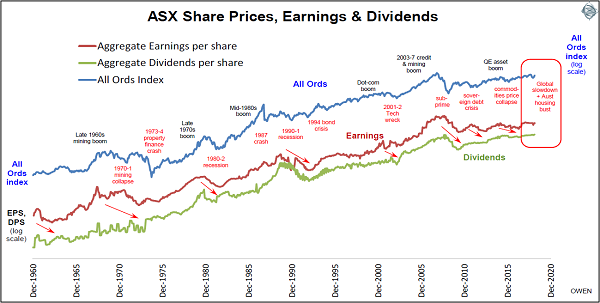

Here the focus is on the broad market, which has generated handsome returns over the long term for those who study the underlying drivers and get the timing right. The chart shows the broad market index (blue line) since 1960, together with aggregate earnings per share (maroon), and aggregate dividends per share (green). This highlights the significant drops in earnings and dividends in each of the major economic recessions and slowdowns.

Click to enlarge

The February 2019 reporting season

Aggregate profits and dividends rose in 2018, but most of it was from the big miners and their windfall gains from the fortuitous rebound in commodities prices since early 2016, and recoveries from the big losses in the oil and gas, steel and mining sectors from the 2015 commodities collapse.

The big banks - the main engines of profits and dividends - all reported poor full year results (CBA has a June year and the other three have September years). Profits in the big banks were down across the board with weak revenue growth and rising costs of regulatory penalties, customer remediation and compliance. As usual, profits were conjured up by fiddling with their bad debt provisions, which are still at wafer-thin levels and will surely blow out as the residential construction and investment property lending boom deflates.

Dividends were also boosted by two other factors. The first is rising shareholder pressure to return proceeds from sale of mines to shareholders rather than let management waste it on more over-priced acquisitions. The big miners have a long and sorry history of wasting billions of dollars on over-priced acquisitions and projects at boom-time prices, only to write them off when prices inevitably fall when the cycle turns.

The second theme driving dividends this season has been an eagerness to pay out extra dividends to reduce franking balances prior to a possible Labor win at the upcoming Federal election, which would see Labor implement their promised scaling back of franking credit refunds.

Looking ahead to the 2019 profit and dividend picture, the two main sectors look rather weak. Banks will probably suffer lower lending growth and higher costs of remediation and compliance, as well as bad debts from the property slowdown. Miners (including oil and gas) will not repeat their windfall gains as the commodities price rebound of 2016-18 has stalled in the global slowdown. In other sectors, cyclical weakness will probably hit construction, building materials, transport and retailers (including property trusts which are dominated by retail). Telstra is, well, Telstra. Aside from Macquarie, CSL and the big insurers, the other 2,000+ listed companies make little difference to overall market returns.

Miners versus banks: Who wins over the long term?

Australian stock markets have always been dominated by miners and banks, but which sector has been better for shareholder returns?

During February 2019, BHP (including the London end) reclaimed top spot from Commonwealth Bank as Australia’s most valuable company. Banks had enjoyed a stellar run since the early 1990s thanks to their relentless gouging of margins and fees, gobbling up competitors, aggressive cross-selling of internal products, fraudulent selling and a host of other unsavoury practices under their cosy cartel structure and sleepy regulators. But the miners beat the banks in 2016, 2017, 2018, and so far in 2019. Why, and will it last?

Rising commodities prices since early 2016 have driven the recent recovery in mining share prices, while the big banks have been hit by a regulatory backlash and a local housing and construction slowdown. The miners’ lead will wane as commodities prices fall in the global slowdown.

Miners have always been speculators’ favourites. Probably 90% of all companies that were ever listed on Australia’s numerous stock exchanges since the 1850s have been speculative mining ventures. The vast majority disappeared without a trace almost as quickly as they appeared. Shareholders’ funds were pocked by sharp promoters or disappeared down empty holes in the ground. Despite the woeful history of most mining stocks, many thousands of speculative fortunes have been made by ordinary shareholders who struck it rich in the mining booms that come around about every 30 years.

Banks on the other hand have been relatively stable, high dividend-paying ‘safe havens’ (apart from the 1890s and 1930s depressions and a close call in the early 1990s). Compared to miners, banks have mostly been relatively boring.

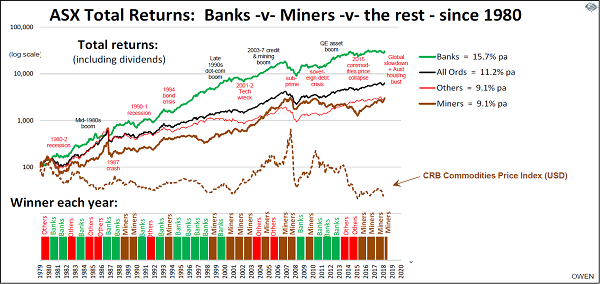

The chart below shows total returns (including dividends) over the past 40 years - from the banks (green line), miners (brown), and the rest of the market (red), compared to the overall market index (black). The banks have won easily with total returns averaging more than 15% per year, compared to just 9% per year from the miners and the rest of the market. The bars in the bottom section show the winner each year.

Click to enlarge

In the past 40 years, banks won in 16 years, miners won in 15, and the rest of the market won in just 9 years. The brown dotted line in the middle is the broad commodities price index, which is the key to mining cycles. Miners bounced back with commodities prices from early 2016 with the Chinese stimulus, US recovery and signs of life in Europe and Japan. The only other years miners won were 1989 and 1980, but that was because banks were hit by mounting bad debts leading into the early 1990s recession, not by rising commodities prices.

Miners will suffer once again when commodities prices fall in the coming global slowdown. As for the banks, the Hayne Report entrenched their market dominance and they should be free to carry on most of their oligopolistic ways with a few minor tweaks to appease regulators.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.