Contrary to popular perception, the emerging market asset class has delivered strong long-term returns.

Since the MSCI Emerging Market (EM) index was launched in 1988, it has compounded at 9% in US dollar terms annually, compared to 11% for the S&P 500. Analyzing trailing returns at the bottom of a cycle can also understate this reality.

Foreign investment in emerging markets has waned over recent years due to negative sentiment toward the asset class that today resembles what we observed in the US during the financial crisis or in the energy sector during the COVID pandemic.

But while other investors may view these assets as out of favor, we see an opportunity.

Why consider investing in emerging markets now

Superior GDP growth, favorable demographics, or relative valuations by themselves are not compelling enough reasons. China’s mediocre long-term equity returns are a great case study showing that these variables alone are not sufficient to drive performance.

Instead, our North Star is corporate earnings. In our office is a sign that reads, “Earnings are like gravity,” because we believe stock prices follow earnings over the long term. Thus, we are turning positive on emerging markets primarily due to the improving earnings outlook.

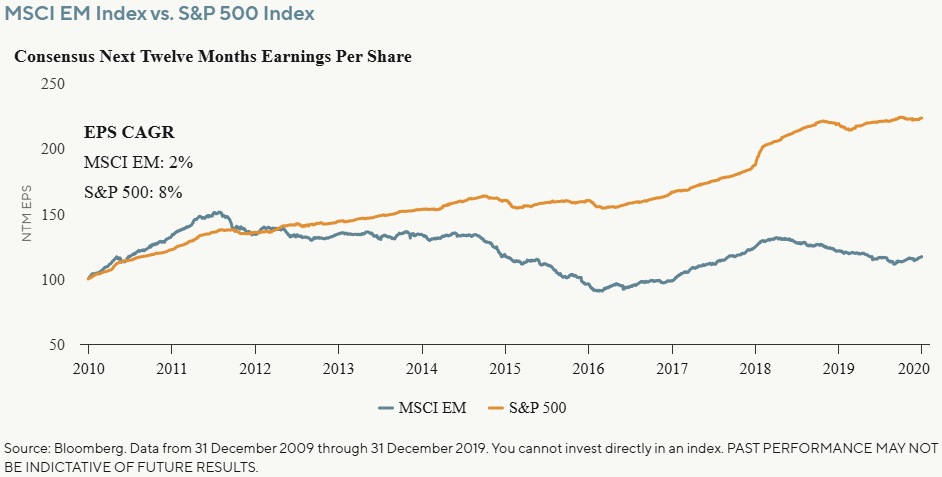

In our opinion, the single biggest driver behind the S&P 500’s massive outperformance over the past decade has been earnings growth. After minimal earnings growth in the 2000s, the S&P 500’s earnings accelerated to an 8% CAGR in the 2010s, largely driven by the technology sector. In contrast, the MSCI EM’s earnings were basically flat during this time.

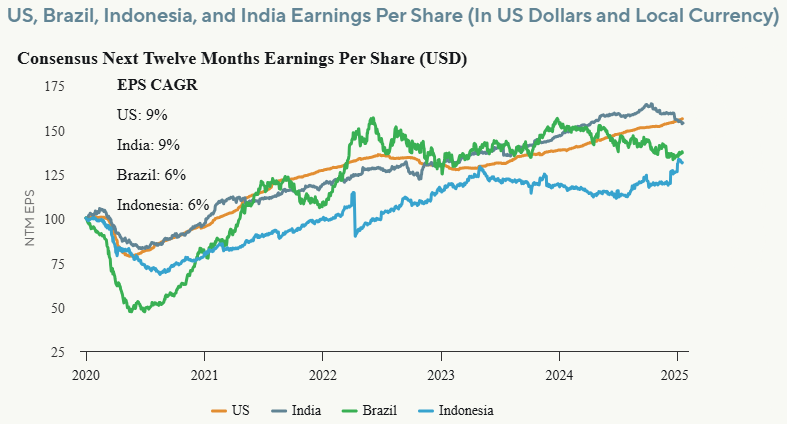

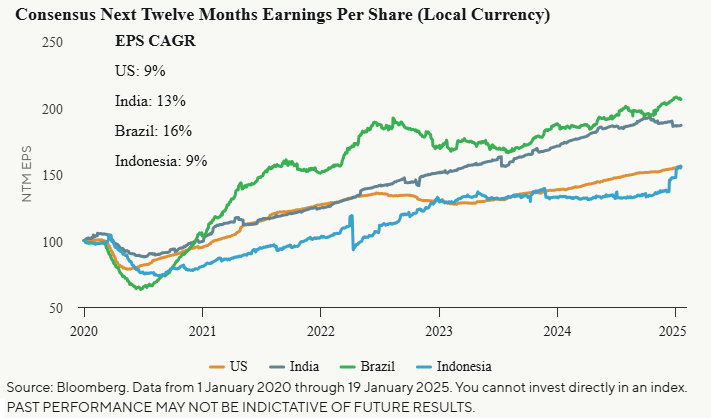

However, earnings have started to recover for emerging markets in both local currency and US dollar terms. We will focus on three of our favorites—India, Indonesia, and Brazil—but these are by no means the only markets we are excited about. Since January 2020, these three countries have delivered earnings growth comparable to the S&P 500, despite having minimal technology exposure.

Drivers of the earnings inflection in emerging markets

1. Improving Economic Policies

Good economic times often lead to bad economic policies, and vice versa. In our opinion, it is only in the darkest times that politicians are willing to make the unpopular but necessary decisions required to stabilize an economy, such as slashing spending. The early 2000s bull market led to poor economic policies, including increased spending, trade deficits, excessive leverage, corruption, and government intervention, to name a few.

However, the sharp slowdown in emerging markets during the 2010s resulted in pro-business leaders taking office: Narendra Modi in India, Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Joko Widodo in Indonesia. We have discussed their economic policies at length in prior GQG research papers.

One Indian CEO remarked how “the Indian government went from slapping red tape on businesses to rolling out a red carpet for them” under the Modi administration. Unlike in the developed world, trade deficits and inflation in emerging markets have improved dramatically over the past few years.

India, Indonesia, and Brazil each reduced their trade deficits from 4% to 5% of GDP to 1% to 2% over the past decade, whereas the US went in the opposite direction. Similarly, inflation improved from roughly 10% at its peak to mid-single digits.

In contrast, the developed world seems to be making the same economic mistakes the emerging world made in the 2000s. As of this writing, the US has a 6% fiscal deficit despite a booming economy, a 4% trade deficit, and a 120% debt-to-GDP ratio.

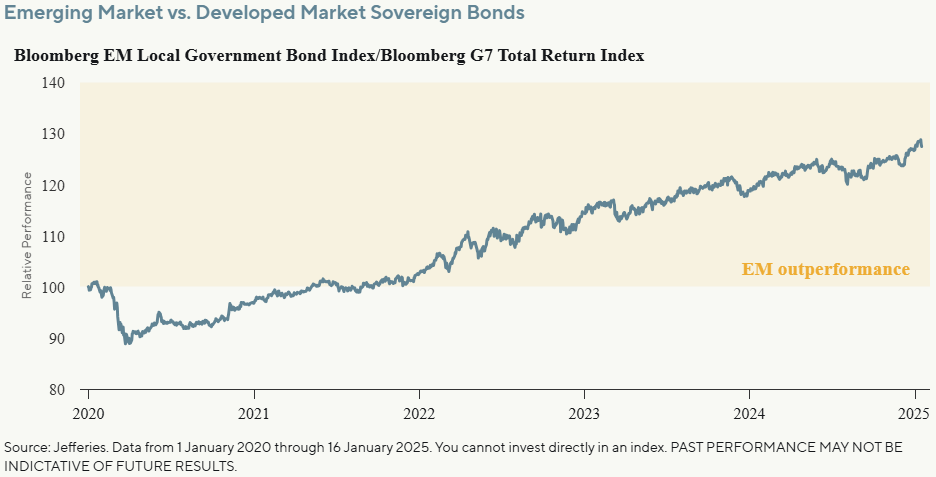

Europe is in an even tougher situation given its stagnating economy, stifling regulatory environment, and political turmoil. Bond markets have been sending a clear message with emerging market sovereign bonds consistently outperforming developed market bonds in recent years.

2. Stronger Banking Systems

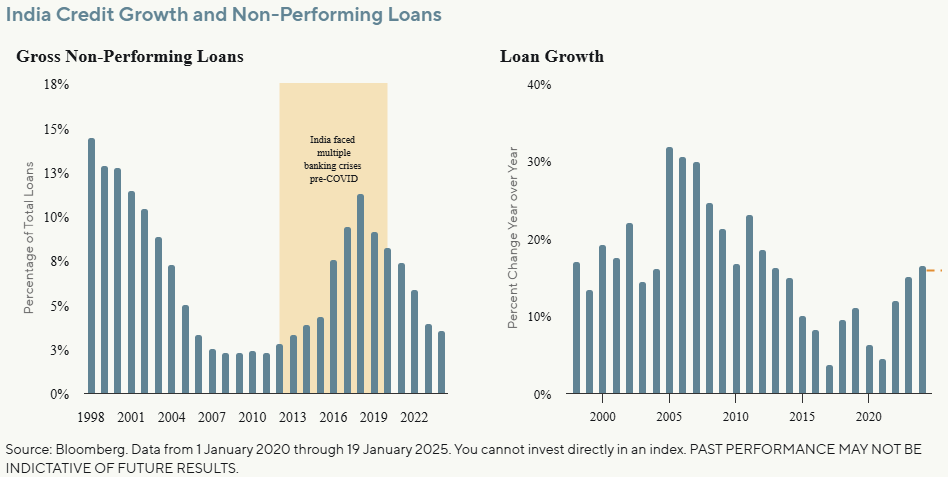

Today, most emerging market banking systems are in solid shape, in our view, as loan growth has improved, and corporate balance sheets have been cleaned up. It is also important to remember that banks have an outsized impact on emerging market equity markets as they are typically the largest public stocks in each country. The financial sector makes up approximately 25% of the MSCI EM benchmark and accounts for three of the five biggest public companies in Indonesia.

The developed world faced a banking crisis in 2008, but India, Indonesia, and Brazil experienced one nearly a decade later. Buoyed by the early 2000s bull market, local corporations of these emerging market countries took on excessive debt and paid the price once growth slowed down.

As a result, Brazil’s two biggest companies, Petrobras and Vale, nearly went bankrupt in the mid-2010s. This had a cascading impact on these countries’ banking systems, particularly the state-owned banks. Non-performing loans surged, liquidity dried up, and banks sharply curtailed lending.

Meanwhile, India’s non-performing loans crossed 10% of GDP in 2018. Any economy would struggle in this environment, as credit has a multiplier impact across sectors such as housing, autos, and infrastructure.

Emerging markets provide true diversification

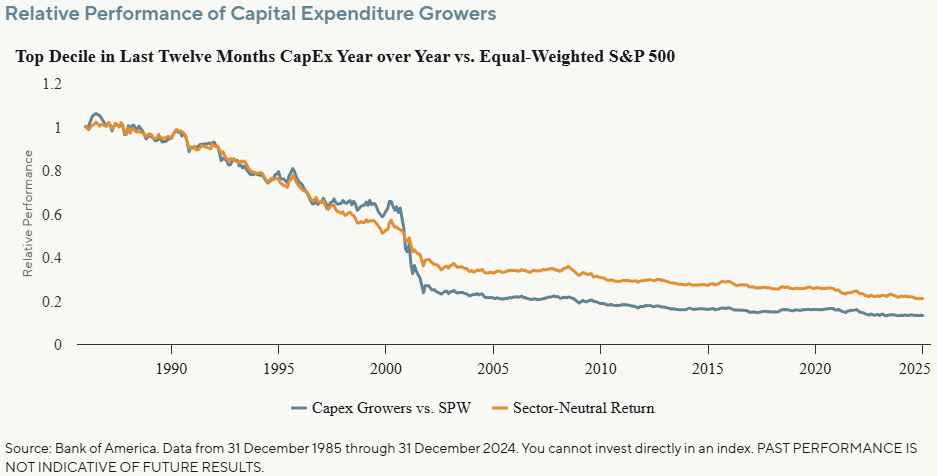

While we remain positive on the US given its plethora of high-quality companies, we are starting to see clouds on the horizon. Most notably, we believe the massive AI-driven capital expenditure surge in the technology sector could soon start weighing on S&P 500 earnings growth.

Prior innovations, such as railroads, electricity, shale, and telecom, also went through similar capital expenditure cycles, and they did not end well. Rising fiscal and trade deficits could also eventually negatively impact the dollar, similar to the early 2000s.

From a diversification perspective, we also believe investors should consider how much of their overall portfolio is likely to behave similarly to US technology. This may be a much larger portion of their portfolio than they realize. Emerging markets offer an idiosyncratic return profile and have historically moved in cycles opposite to those of the S&P 500.

Riding the wave in emerging markets

On a bottom-up basis, we are finding many attractive investment opportunities in emerging markets. Especially in the four following markets.

India

India’s Sensex is one of the only major indexes that has matched the S&P 500’s earnings growth over the long term. Over the past 20 years, both the US and India have delivered approximately 7% US dollar earnings per share (EPS) growth.1 Like the US, India offers a large addressable market, a stable democracy with rule of law, and a dynamic private sector. Unlike its Asian peers, India’s consumption-driven economy helps insulate the country from global volatility.

Given the country’s size and growth outlook, we believe India could be the main driver of emerging market earnings over the next cycle, like Malaysia and China played previously. In particular, we are very excited about the country’s infrastructure sector, which has grown earnings by over mid-teens annually.

The main pushback with India is valuation. However, after the recent correction, the Sensex now trades at its pre-COVID multiple of 20 times EPS, despite better earnings growth.

Indonesia

Indonesia offers many of the same characteristics as India (pro-business government and stable democracy) that have resulted in attractive long-term returns. Since the beginning of the 21st century, Indonesia has delivered 9% annualized US dollar returns compared to India’s 10% and the US’s 8%.1

Relative to India, we think Indonesia will likely see slower earnings growth but higher dividends. For example, the country’s index currently offers an attractive 5% dividend yield. We are positive on the big banks, which could deliver low-double-digit earnings growth and a 20% return on equity.

Brazil

Brazil faced its equivalent of the Great Depression during the 2010s but is well on the path to recovery, with its economy consistently surprising to the upside post-COVID. Furthermore, Brazil’s returns largely come from dividends with the country’s Ibovespa index now yielding 7%. We continue to see investment opportunity in Petrobras, Brazil’s oil major, which operates some of the highest quality oil reserves in the world and offers a mid-teens dividend yield.

The main downside in Brazil is the Lula administration’s fiscal spending, in our opinion. However, we are being paid to wait, given the robust dividends and elections less than two years away. Additionally, we believe a company like Petrobras is relatively immune, given its significant dollar revenue and dividends, which help plug the country’s fiscal gap.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Similar to Asia in a previous cycle, the Middle East is transforming into a new frontier for investing as the region opens its economy to foreign investment, implements pro-business reforms, and rapidly attracts expatriates. The UAE is copying the Singaporean playbook and transforming into a global financial hub.

Most UAE companies offer a mid-single-digit dividend yield with high-single-digit earnings growth in a stable currency. The property sector is likely to be one of the biggest beneficiaries from the country’s transformation, in our view, and could see high-teens earnings growth.

Active management is key

Understanding cycles is a critical component of navigating financial markets over the long run. Both the US and emerging markets have experienced lost decades in the past, and it is a mistake to simply extrapolate recent performance.

Economic policies, corporate earnings, and bond markets have already inflected positively in many emerging markets. While not guaranteed, history suggests that an improving relative earnings outlook could also drive higher multiples and a weaker dollar, which would be a triple tailwind for emerging markets.

There are many potential risks to monitor, such as the implications of Trump 2.0, but we believe investors with a longer-term perspective should consider adding emerging markets as part of a diversified portfolio.

Sid Jain is a deputy portfolio manager at GQG Partners. This article contains general information only, does not contain any personal advice and does not consider any prospective investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs.