The world’s bond markets and stock markets not only attract vast sums of money, but also a lot of financial commentary in newsletters and newspapers.

In many of those commentaries, there’s a presumption that both bonds and stocks should always trade in an overtly consistent and predictable manner – stronger economic growth means higher yields and higher share prices, while slower growth means the opposite.

When this doesn’t happen, analysts often fall over themselves to argue that one market is ‘right’ and that investors in the other should be paying more attention. Even without the overlay of a titanic clash, analysts are prone to discuss contrary price action in the markets as if they’re responding with different mindsets.

I saw an example of this recently in the Australian Financial Review. It was an article mostly about US bond yields, which were said to be falling because of concerns that COVID and expected tighter policy were combining to reduce the economic growth outlook. However, it finished with the following statement:

“Equity markets appear decidedly more upbeat than the bond market … The S&P 500 reclaimed a record high on Monday and the S&P/ASX 200 Index hit a fresh peak on Tuesday.”

However, bonds and shares are two very different asset classes, so why should they trade in a correlated fashion? Standard portfolio optimisation theory relies on different asset classes being uncorrelated, otherwise the eggs aren’t being placed in different baskets.

What’s going on here?

Correlation history

A clue can be found in the history of the correlation between these markets. From here on I’m focused on the US which dominates daily trading in all markets.

In recent history, we find that there has actually tended to be a positive correlation. That is, yields and stock prices move together in the same direction.

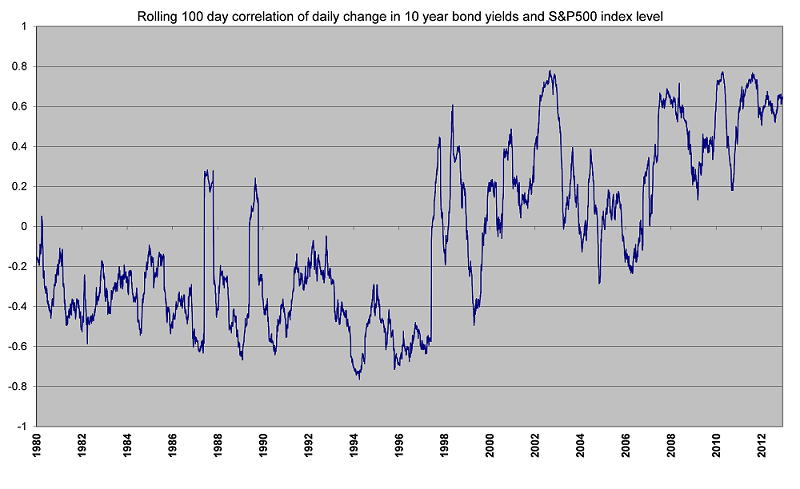

The following chart shows the rolling 100-day correlation of daily changes in 10-year US Treasury yields and the S&P500 index since 1980. Clearly, for just over half of the last 40 years, the correlation was negative. Then from 1998 until 2007, the correlation fluctuated quite markedly perhaps with a slight positive bias but nothing significant.

Since 2007, however, the correlation has been positive and, to be honest, that makes it look like the last four decades can be split in half – 20 years of negative correlation then a shift to generally positive for the last 20 years. That’s certainly sufficient evidence to convince a lot of people that, right now, stocks and bonds should be expected to trade in the same direction most of the time.

Source: Bloomberg, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

However, I suggest that just because there’s been a positive correlation so far in the 21st century, that doesn’t mean that it’s going to stay that way.

Taking a longer-term view shows that the recent period is actually a rarity. In an excellent paper written in 2014, Ewan Rankin and Muhummed Shah Idil of the Reserve Bank of Australia studied "A Century of Stock-Bond Correlations". They demonstrated that the short-term correlation between US stock and bond markets has always fluctuated considerably but has mostly been negative during the past 100 years.

The main exceptions were during recessions, when bond yields and share prices both fell, thus creating a positive correlation. It’s only since the GFC that this positive correlation has been evident for a prolonged period and they concluded that the current experience reflects the severe impact of the GFC on the uncertainty that surrounds expectations for economic growth.

That is, the market is behaving as if we’re in a recession, even when growth has been positive.

It's not a battle! Nature of the two asset classes

Even so, it’s incorrect to depict periods when the markets move in different directions as meaning that traders in one market have it ‘right’ and those in the other are ‘wrong’. It’s not a battle!

In reality, both bonds and shares are always responding to the same set of information in an appropriate way for the time, circumstances and nature of the asset class. Every time during my career that I've looked into what's going on there's usually a perfectly good explanation about why two different asset classes 'seem' to be moving in conflicting directions. Not always a simple explanation, but a good one.

That explanation is usually found in the different inputs to the valuation of different asset classes. Bonds have fixed income for a limited period of time, whereas shares are perpetual cash flow entities.

Bonds thus respond to changes in macroeconomic trends and central bank policy settings in a consistent manner: stronger growth = tighter policy = higher yields, and vice versa. Note, however, that even within the bond market, not all securities respond identically. The yield curve is not constant, as long-term and short-term bonds can respond to different degrees to the same cash rate change. The curve tends to steepen during periods of falling cash rates and flatten when policy is being tightened.

So if different bonds react differently, why should we expect a different asset class to behave itself?

Shares factor these same changes into their valuations in a more complex manner. Changing bond yields feed into the discount rate for valuing earnings, but unlike bonds the earnings of shares can also vary. So sometimes when bond yields are rising share prices will also rise because there’s a stronger economy driving better earnings growth, but sometimes shares will fall because of the higher discount rate.

There can also be other factors at play. Sometimes, stock markets might validly look at profit-enhancing micro trends when the bond market is looking at the macro consequences.

Finally, there can be timing differences because the behaviour of each market is part of the information that the other market needs to price in. The main players in bond markets are more closely watching short-term data trends and predicting the central bank's next move more closely than company analysts.

Once bond yields fall, then that is sometimes the signal to equity market participants to shift their behaviour too. But the bond market doesn't always get its central bank calls right, so stock market players have an appropriate natural wariness about reacting instantly to what the bond market is doing. And bond market traders need to respect the stock market’s direction as well.

Conclusion

The idea of a tussle between stocks and bonds is often used by analysts to create a story and to sound impressive. In reality, both markets are reacting to the world in their own way rather than being engaged in a struggle for supremacy.

When these markets move in different directions, it’s always worth digging a little deeper to understand the dynamic that’s playing out between what are two different types of assets. Both markets are usually ‘right’ (if there is such a thing) and I prefer to think of it as being more of a dance than a battle.

Warren Bird has 40 years experience in public service, business leadership and investment management. He currently serves as an Independent Member of the GESB Investment Committee and was, until recently, the Executive Director of Uniting Financial Services, one of Australia's oldest ethical and ESG fund managers. This article is general information.