The recently legislated tax cuts are welcome for many taxpayers, but they are largely payback for the effects of wage inflation and bracket creep. People often think only of bracket creep as the process where wages push into a higher tax bracket due to inflation.

But it is more encompassing than that, and can also have an effect within marginal tax brackets.

How marginal tax rates work

Consider a tax system with a 30% rate of tax on income in excess of a tax-free threshold of $20,000.

A wage earner on $50,000 will pay $9,000 tax (30% of $50,000 less $20,000), with take-home pay of $41,000.

Suppose wage inflation pushes his salary up 5% to $52,500. The tax bill becomes $9,750, and take home pay $42,750. So net of tax, pay has increased by 4.3%, which is less than the 5% increase in gross earnings.

In this case, wage inflation has not pushed the wage earner into a higher tax bracket, but the wage earner’s net of tax pay has not kept pace with inflation. ‘Bracket creep’ is a bit of a misnomer. It’s more like ‘tax creep’.

To negate so-called bracket creep, the thresholds at which marginal tax rates change should be indexed to inflation. Assume therefore that the tax-free threshold in our example becomes $21,000 (a 5% increase). Then the tax bill becomes $9,450, and net pay $43,050. In this instance, take home pay has also increased by 5%. That is, there is no bracket creep when the tax-free threshold is indexed.

The problem is, governments of the day do not index tax thresholds regularly, meaning wage earners suffer a silent increase in the tax burden.

Bracket creep is an outworking of a progressive tax system, such that the total tax paid as a percentage of income (the average tax rate) increases with income earned. A regressive system does the opposite. A progressive system is constructed by setting higher marginal tax rates at higher income bands.

We have always had a progressive income tax scale in Australia. For example, on the 2018/19 tax scale, someone earning $45,000 pays $5,892 tax, while a taxpayer on $200,000 pays $67,097, or 11.4 times more. Clearly that’s progressive.

Bracket creep is regressive in our progressive tax system

Perversely though, bracket creep acts regressively because average tax rates increase more sharply at lower income levels before flattening out at higher income levels. Bracket creep can act as a drag on the incentive to work and earn more, as every extra dollar pushes the average tax rate higher. At the extreme, it can discourage employment and ambition and encourage tax avoidance.

In general, the more income tax brackets, and the wider the spread of marginal tax rates, the more progressive the tax system. And the more progressive the tax system, the greater the impact of bracket creep.

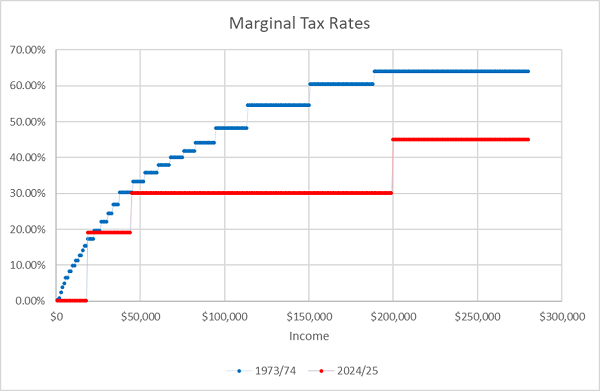

Remarkably in the 1973/74 Australian tax year, there were 29 income tax brackets with a top marginal rate of 66.7%, which yielded a highly-progressive tax scale. And that, coupled with inflation hitting an incredible 15.8% in 1974, meant that bracket creep was a huge issue.

Contrast that with the recently-legislated Coalition tax scale for 2024/25 of only four tax brackets, with a super-sized bracket of income between $45,000 and $200,000 taxed at a marginal rate of 30%, and a top rate of 45% beyond that.

In fact, if we indexed the 29 different tax bracket thresholds in 1973/74 for 51 years of inflation to 2024/25, we can compare the two tax scales at the same income levels. Inflation from 1974 to 2018 averaged 4.9% p.a., then we extrapolate that for another seven years at a more modest rate to reflect current low inflation until 2024/25. The first chart below shows how marginal rates step through increasing income levels for both tax scales. The sheer number of tax brackets in 1973/74, stepping up to a marginal rate of over 60%, is evident.

Progressivity has fallen over time

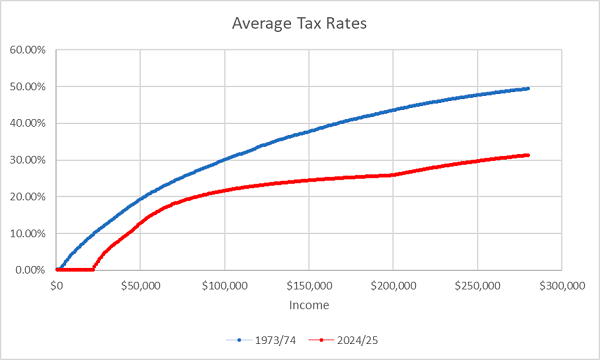

Of perhaps more interest is comparing the average tax rates of the two tax scales, for increasing income levels. In the chart below, the average tax rates have shifted down at all income levels since 1973/74, with a wider gap at the higher income amounts, as a consequence of a flatter 2024/25 curve. It shows progressivity, or the degree to which a tax system is progressive, has fallen. Note, the 2024/25 curve includes the low income tax offset, but excludes the Medicare Levy.

The 2024/25 tax scale is less progressive than previous editions, but someone earning $200,000 will pay nearly 10 times more tax than someone on $45,000.

In terms of revenue collected, Treasury projects that the top quintile of income earners will still pay around 60% of all tax in 2024/25. And a positive consequence of less progressivity of course, is the dampening of the bracket creep effect.

Therefore over time in Australia, we have been trending towards a flatter tax system, where bracket creep becomes less of an issue.

Is there a case for a proportional system?

In fact, one wonders if we will ever reach the extreme, dare we say, of a proportional tax system, where the average tax rate remains the same at all income levels. Just one tax rate, no matter the income. It’s a system that would eliminate the effect of bracket creep entirely and that would be neither progressive or regressive by strict definition.

Such a system would encourage initiative, innovation, further education, and the willingness to earn more, which would in turn stimulate labour supply and exposure to taxation. In essence, a proportional tax system would encourage low wage earners to earn more and high wage earners not to earn less. It would be simple to maintain and manage, and tax avoidance strategies would not be as prominent.

On the other hand, high income earners would pay less tax proportionally, and low income earners more. But average tax rates for high income earners have been steadily reducing over time. Low income tax offsets and safety nets could remain in place, ensuring low income earners are no worse off. While investment income earners would no longer have a nil tax environment to minimise tax, which would surely appease the franking credits detractors, for example.

Interestingly, proportional tax systems already exist in some East European countries, some having modified versions with tax-free thresholds or tax offsets at low income levels. Efficiencies in tax compliance have been gained in those countries.

Significantly though, a proportional tax system would ensure that the incumbent government could not increase the tax take by stealth.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary.