Asset allocation (AA) is the process of constructing an investment portfolio among different asset classes, such as shares (domestic and international), bonds, property (listed REITs and direct), fixed interest securities, cash etc. The goal is to create a diversified portfolio that matches appropriate risk with appropriate returns for that risk. By investing in a variety of assets that are not closely correlated, investors can potentially earn fairly predictable returns over a period of say five years than if they were to invest in just one asset class.

SMSF trustees must understand the level of investment risk that the SMSF beneficiaries should be or are prepared to accept. An assessment of the appropriate target rate of return from the portfolio – noting potential capital gains and income – can then be made. The return should consider the benefits of compounding from full reinvestment (during the accumulation stage) or part reinvestment of the income (at pension stage).

Guidelines for asset allocation

Some key guides that I would encourage trustees to follow are:

- A short-term focus on returns should be avoided unless the beneficiaries are very elderly;

- The rate of return target (per annum) should focus on at least five years duration noting that over the longer term, economic growth is assured;

- AA should be dynamically reviewed as economic events or observations are noted – in particular bond yields need to be monitored;

- The AA analysis and assessment is best undertaken with the help and counsel of a qualified financial advisor, who can act as both a sounding board and a guide for an SMSF trustee.

The design of asset allocation for an SMSF starts from an understanding of a ‘balanced’ portfolio. In my view, a balanced asset allocation weighs equally to growth assets and to capital stable income-yielding assets. However, I acknowledge that there is no established or agreed industry position on what constitutes a balanced portfolio.

The proposed or advised AA moves from balanced based on risk adjustments so that a ‘conservative’ AA is created by weighting the portfolio to lower risk, capital stable and/or income assets. Alternatively, AA will move towards ‘growth or aggressive’ by weighting to higher risk, more volatile equity-type assets.

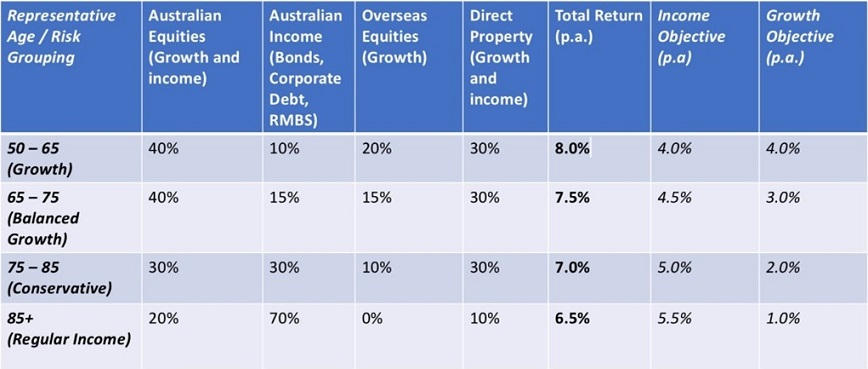

My table below is a general advice table for an SMSF, and readers should note that it has only one variable input – the age of the beneficiary. The outputs of the table (projected 5-year returns that include franking) simply suggest that a beneficiary will normally seek lower risk and accept lower (but more stable) returns as they grow older.

Source: Clime Asset Management

Clearly risk analysis requires more than a reflection of age. A comprehensive analysis considers a range of other issues (personal circumstances) that include health, non-super assets, home ownership and a desired quality of life (running expenses), dependents, and even psychological make-up. If exposure to volatile assets is going to keep someone from sleeping well, perhaps it should be avoided! Nevertheless, the table does provide an insight into how prospective investment returns change with asset allocation.

As noted above, the total targeted returns are expected to be generated from income and capital gains over a five year projection. As noted earlier the allocation to asset classes and the expected returns should be dynamically monitored. Changes to expected returns from the tailwinds or headwinds generally caused by actual or predicted bond yield movements will affect AA. Bond yield analysis sets the basis for determining the desired returns from assets and thereby the entry prices for acquiring assets.

What follows are my current views on the influences to asset prices, including the dilemma of rising long-dated bond yields, why they will probably rise further, and the effect this will have on asset prices.

What could affect asset returns

From the table above readers will glean that the main asset classes that I focus on are as follows:

Growth with income

- Australian and international equities plus listed REITs

Growth and income

- Direct property

Income

- Bonds

- Corporate debt

- Mortgage backed securities

- Hybrids

To begin, context is important. Where have we been?

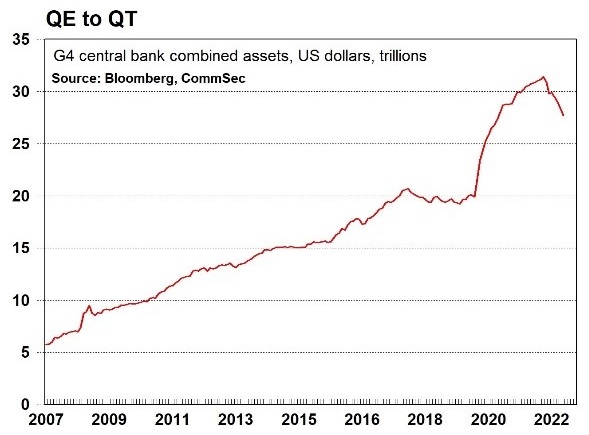

Asset markets are emerging from a decade of rampant bond yield manipulation undertaken by the world’s largest central banks. Quantitative easing (QE) was the tool utilized by central banks.

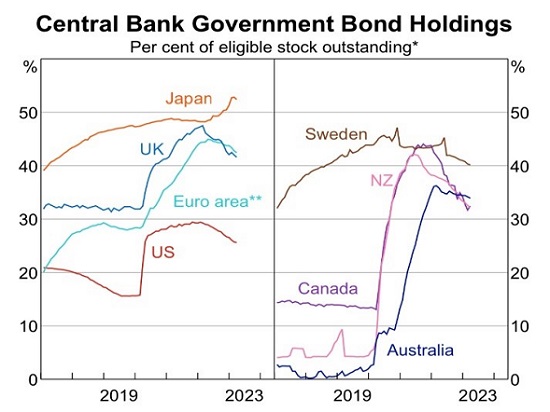

In the main, central banks effectively printed money, targeted a particular bond yield/s in markets and then intervened by secondary market purchases to attain that yield. Over time, central banks became the largest owners of their government bonds. For instance, in the US, the Federal Reserve owns about US$7 trillion of bonds out of the approximate $30 trillion on issue. In Japan, the BoJ owns around 50% of all Japanese government bonds.

Source: RBA chart pack

The manipulation of bond yields allowed governments to run large fiscal deficits, avoid fiscal discipline and grow government debt with a low cost of servicing the same. Fiscal largesse had become a universal policy setting across the US, Europe and Japan, with its sustainability not questioned. Even now, there is scant regard given to it, but it will in time be reflected by higher bond yields unless central banks intervene again.

Readers will recall that for sustained periods over the last 10 years, Japanese, German and Swiss long dated bonds traded with a negative yield. Poorly-rated bonds issued by the Italian, Greek or Spanish governments (for instance) often traded at yields below the highly-rated Australian bond. During the pandemic, US and Australian long-dated bonds traded at yields below 1%.

The world bond market passed through a sustained period – after the GFC – where bond yields were not affected by the normal yield determinants that include:

- observed inflation and the risk of future inflation,

- currency risk for non-domestic buyers; and

- default and/or credit rating risk of the issuer.

Effectively, QE blew away all of these market pricing influences which are fundamental to sober valuation metrics. Thus, the so-called but vitally important ‘risk free’ return was debased and this affected the price of all asset classes.

It is clear that bond yields were not driven by the open or free market. Whilst there were willing buyers and sellers meeting in the bond market to trade their positions, the daily pricing of bonds was dictated by central banks. Today, that is still the case in Japan, but in other major economies central banks are indicating that they intend to reduce their influence over bond yields.

In effect, QE is moving to QT (Quantitative Tightening) whereby central banks reduce their bond holdings by allowing them to mature (redeem) and by not reinvesting the proceeds, or by selling them. The start of QT in the US is illustrated below, and the same monetary policies are being reflected across Europe. QT in Australia has slowly begun and it will have a significant influence on the bond market from 2024 onwards if the RBA begins to offload the majority of its bond holdings.

QT will add to the supply of bond issuance by governments and more so if governments do not concurrently bring their fiscal deficits back into order. The effect of a seemingly endless supply of bonds means that bond prices will be under pressure and yields will likely rise. This explains why US 10-year bond yields are beginning to rise even whilst measures of US inflation decline. I expect a similar scenario to play out across European and Australian bond markets.

How higher yields may affect asset allocation

Rising bond yields mean that the ‘risk free rate of return’ or the ‘risk free investment hurdle’ will lift and be a headwind for the pricing of all assets in the coming few years. This leads me to the following conclusions for both AA and assets prices over the next year:

1. Long dated bond yields (past five years) will continue to rise leading to capital losses that offset higher yields.

2. Shorter dated bonds (maturity of less than two years) are preferred as they currently match or exceed expected inflation and the risk of capital loss (via market prices) is not high.

3. Rated corporate debt is preferred to bonds as the repricing of long-dated bonds flows through. Staying short in maturity is desirable (up to three years). Mortgage-backed securities and hybrids are already seeing higher running yields and will be weighted into diversified portfolios as a core income generator.

4. Cash rate settings will remain elevated for longer than generally expected. Whilst cash rates in the US will likely fall during 2024, the same cannot be expected for Europe or Australia.

5. Equity P/E ratios will moderately decline with bond prices, so investors need to focus on companies that will grow earnings greater than and offset P/E compression. This will be difficult (short term) as economies slow with tight credit conditions being maintained over the next year.

6. Importantly, the longer-term growth outlook for Australia remains positive and far superior to Europe. The current weak AUD reflects negative “real” cash rates that won’t reverse until mid-2024. This suggests that a re-weighting to Australian equities from international equities or a currency hedge should be considered at some point early in 2024.

7. Rising bond yields will lead to a lift in capitalization rates for property with the commercial sector remaining under pressure. Non-discretionary retail (suburban shopping centres), industrial and agriculture will also experience cap-rate compression but offer better growth to offset this and particularly taking a five-year view.

AA analysis should not be dogmatic, and we must always consider what could go wrong with the forecast of bond yields or the risk free rate of return.

In my view, the key risk to the above view is the potential for the reintroduction of QE, leading to the reinstatement of bond price and yield manipulation that supports the servicing of government debt.

I suspect that there will be a bond yield level set by central banks in each major economy at which they will act to protect the financial viability of their governments. A burgeoning interest bill flowing from a bond market that panics has the potential to destroy a government’s fiscal policy and create economic calamity. It will be avoided at all costs and so we must monitor whether QE returns, or QT slows.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.