History may well judge the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic as much an emotive and financial panic as a health crisis that led to a recession or depression. More like a GFC Mark II. In a fortnight during March, we saw $US30 trillion (30%) wiped off world stock markets that had begun the year at around $US100 trillion. They had recovered to be 15% below that peak in mid-August. World GDP in 2020 has been forecast to fall 5%, and even with growth in 2021, GDP would be still lower than 2019.

Having been scared witless by panicky leaders, the medical world, and 24/7 sensationalist media, the public has not been given perspective or options, so many wanted immediate ‘safety’ since they believed they had a high chance of catching and dying from the dreaded virus. A grossly exaggerated fear, given that the world will have lost a miniscule 0.015% of its population from COVID-19 in 2020, lower than the average respiratory death rate each year.

Pandemic perspective

How on earth was COVID-19 allowed to panic nations and the world? The reality of death in society does not justify the madness that has evolved, as we see in the data below.

Some additional perspective for Australia can be gained from the following facts.

- 13 people died from COVID-19 in March-August 2020, on average, each week

- 154 people die of all respiratory diseases on average each week

- 3,220 people die from all causes on average each week and every week.

Only the miniscule number of COVID-19 deaths received saturation media coverage. Only a handful of other deaths were mentioned from murder, road and other accidents and the death of somebody famous.

Didn’t other deaths count or matter as much as a virus death? Is there not as much tragedy with the other 3,200 or more deaths every week in Australia?

So, why can’t governments tell their citizens what tiny chances there are of dying from respiratory diseases at large, compared with all other causes of death, and even less from COVID-19 by itself? And why saturate media with ‘positive cases’ when it is only deaths that matter in the final analysis?

Why are we scaring people out of their minds, when the facts do not provide justification? It is almost as if mediaeval witchdoctors have taken charge of our lives and livelihoods (the economy).

Short history of pandemics

Epidemics and pandemics are an integral part of human history, with each outbreak bearing both social and economic costs. The world has endured other outbreaks over the past century. If the early decades of this new century are a reliable indicator, we can expect to see more in the future.

The first table below outlines the main epidemics and pandemics that have been observed in recent history, when and where they struck and the resulting death toll.

The two standouts were the Spanish Flu and HIV/AIDS. The first, which occurred in 1918–20, resulted in over 50 million deaths (>2.5% of the population); and the second, which was first observed in the 1960s and is still present today, has resulted in 30 million deaths to date (0.6% of the average population until now).

The most recently discovered coronavirus, COVID-19, spread rapidly worldwide. The economic impact of COVID-19 on global GDP and stock markets is proving more severe than was anticipated, and we are yet to see the full extent of the damage.

Increased economic vulnerability

A simple statistic reveals the vulnerability of the world today: in 1950 only 1% of the population were international tourists compared to 20% in 2020. So, diseases can go pandemic more easily and more speedily. Counterbalancing this extreme risk is modern medical research which can result in vaccines and antidotes. Many countries reckon they have the response, so here’s hoping.

The epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, China, dominates (near half) the world’s manufacturing output, and that has created an unexpected problem with the supply chains of goods.

In short, the world economy now has a lot more international interdependence between economies and businesses. Exports had trebled their percentage share of the world’s GDP from 10% to 30% over the past 70 years.

It is sobering to know that governments in Australia shutdown tourism (2.8% of GDP), restaurants (1%), international air travel (1.3%), entertainment (> 1%) and other direct or collaterally damaged industries (estimated 8% minimum) or around 15% of the economy. We will have lost 5-7.5% of GDP and possibly on our way to a depression (two years in succession).

The Ruthven Institute’s provisional forecast over the next five years is shown below.

The financial impact

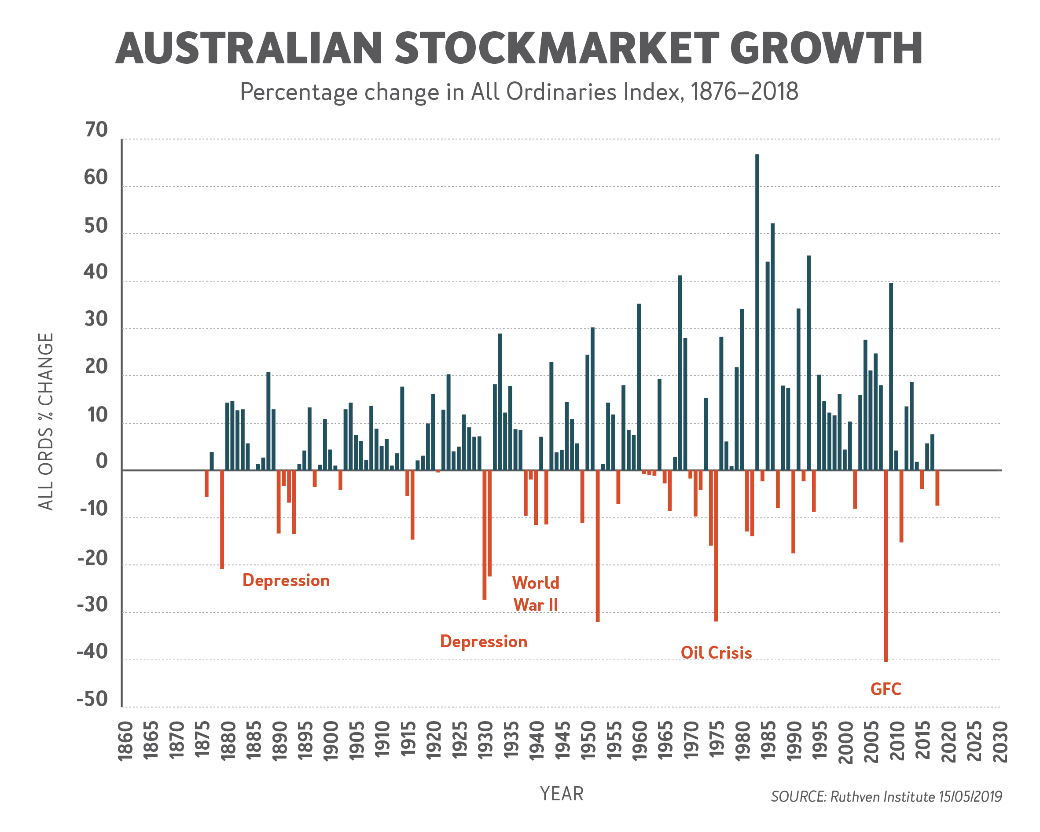

Businesses and investors can be just as spooked with emotional (populist) responses as the public is with diseases. Yet again the stock markets have gone crazy. They have a habit of exaggerating threats as well as exaggerating opportunities, as the chart below reminds us. So, we are on a wild ride, despite the actual economy (GDP) of Australia being nowhere near as volatile as these deviations.

The huge rises and falls in the stock markets are the usual madness of crowds (as expounded by Charles Mackay in his 1841 book: Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds).

We have been on some doozies before, including -40% in 2008. We have had four calendar years of falls of around 30% since Federation due to two World Wars, an oil crisis and the GFC.

Where to from here?

The long ‘tunnel’ in the chart below shows where we seemed to be heading before COVID-19 changed everything. The fall in March was -26% (and 31% from our record high in February). This was panic of the magnitude of the GFC, which was caused by sub-prime mortgages and other unethical if not also criminal behavior in financial markets. The market has recovered to be around 15% below the peak but for how long?

So, what are the lessons learned?

Predicting future epidemics and pandemics is easy: they will continue to happen. But knowing what disease, how dangerous, and when it will strike isn’t easy at all. The world has had 14 pandemics over the past 100 years to 2020, averaging seven years apart and averaging <5 % of annual deaths of the population each year. Only three were terrifying (Spanish Flu, Smallpox and AIDS).

So, it is well to remember that >95% of deaths are unrelated to pandemics. Getting panicky and frantic is no substitute for perspective, rational measures and balancing human impacts with ongoing livelihood impacts (business and the economy). Most of the COVID-19 deaths are with the elderly, meaning quarantining the under-65s that create the bulk of our wealth each year is questionable. What will probably be non-negotiable are: quarantining the most vulnerable (over 70-year-olds) and infected, social distancing and masking.

Perhaps the best news, for those prepared to take the long-term view, is that complacency in both health and interconnective trade dependencies is likely to give way to better planning, safer strategies and alliances, and contingency plans.

And perhaps another permanent change is likely to take place with more virtual workplaces, more virtual meetings and more flexibility via increased partial working from home and videoconferencing via the likes of Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Facebook et al. These practices have been in place or available for many years, but they are becoming more user-friendly, of higher quality and offering more features. They will become de rigueur as a result of the pandemic.

Phil Ruthven AO is Founder of the Ruthven Institute, Founder of IBISWorld and widely recognised as Australia’s leading futurist.