This series on investment diversification has focussed on the mathematically precise world of expected returns, risk and correlations. But modern portfolio theory assumes a world without fees and taxes where all investors have the same time horizon and access to the same information. It also assumes investors are able to interpret and act on details in the same way and have identical unbiased expectations regarding the future. In the real world of investing, these assumptions are too simplistic.

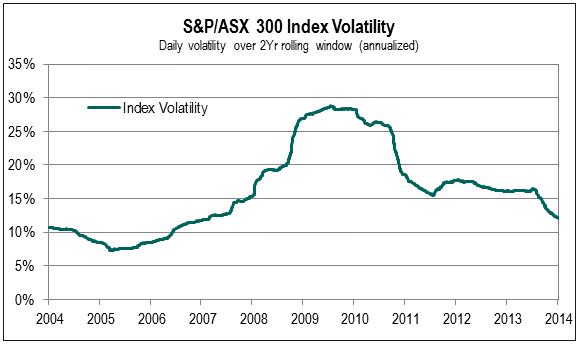

Consider investment forecasting. Correlations, rather than being static, change over time, and risk (however defined) is no more stable. Volatility is itself volatile, as the below chart illustrates:

Data supplied by S&P Dow Jones Indices

The previous article used the terms risk and volatility interchangeably. Why? Because modern portfolio theory holds that volatility of returns is the most appropriate measure of risk. But is this the way people actually view risk?

In over a decade of advising individual clients, nobody asked me about their portfolio’s standard deviation, or how it sat relative to some theoretical efficient frontier. Clients had a keener interest in the change in portfolio value between review meetings, and paid far more attention when these were significantly negative than equivalently positive. In behavioural finance, this asymmetric concern is known as loss aversion. Therefore, let’s put to one side the neat world of modern portfolio theory and consider instead how diversification can be applied to real-world retirement planning.

Framing retirement objectives appropriately

Why bother saving for retirement at all? We do so to smooth our lifetime consumption. If we did not (with charity and social security offering inadequate safeguards), we would swing from exuberant spending in our working years to relative poverty in retirement. Modern portfolio theory forces a single-period risk/return frame onto individuals, when focus might be better directed toward a multi-period consumption frame. A schism exists in the understanding of risk between superannuation trustees and members. Trustees view risk via a text book definition of volatility (standard deviation). Members see risk as a failure to generate sufficient purchasing power in retirement to allow for a preferred level of consumption through it. Whose view of risk is more relevant? Whose risk is being managed?

Funding retirement consumption

It is possible to estimate the value today of the future cost of retirement. It is the present value sum of each year’s expected cost of living for the number of expected retirement years.

Consider an example of a recently retired 65-year-old male. Using the current Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) retirement standards for a single person ($23,283 p.a. for a modest lifestyle and $42,254 p.a. for a comfortable lifestyle), the total retirement cost today sums to $336,000 for the modest lifestyle and $610,000 for its comfortable equivalent. A 65-year-old female would require $374,000 and $679,000 respectively, due to higher life expectancy.

Whilst these numbers are sensitive to inflation and discount rate assumptions, and subject to some variability due to heterogeneous later-life health care costs and longevity risk, they provide a valuable insight into retirement expenditure on average.

Armed with a measure of retirement cost, we now have a basis for comparing these prospective liabilities against retirement assets. To do so we need, however, to consider the totality of assets capable of funding retirement.

It is unlikely that the average retiring 65-year-old male will have $610,000 in superannuation. APRA data currently suggests $151,000 as a more likely balance. Such a large superannuation balance may not, however, be necessary for two reasons:

1. The government age pension

The age pension is effectively a government-backed lifetime indexed annuity. One recent study estimated the value to life expectancy of the full age pension is $377,000 for a 65-year-old male. As some 80% of retirees will receive at least part age pension, it will continue to remain an important ‘shadow retirement asset’ (despite the changes foreshadowed in the government’s 2014/15 Budget).

2. Other non-superannuation assets

Non-super assets such as shares and property play an important role in real-world retirement funding. A recently released Melbourne Institute/Towers Watson working paper calculated median wealth (excluding the family home) for those aged 65 – 69 years at around $389,000. Critically, non-super assets account for over 67% of total financial wealth.

Diversification in an asset-liability framework

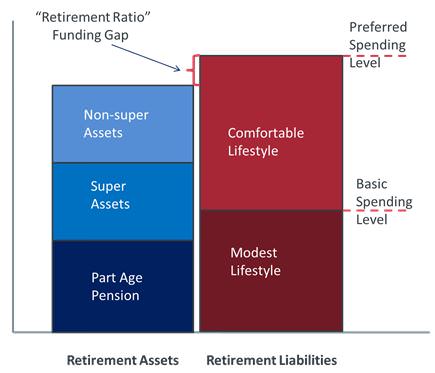

Putting all the pieces together, it is possible to consider retirement planning as an asset-liability matching exercise comprised of various layers as depicted below:

The aim of retirement planning becomes the attainment of a ‘retirement ratio’ of at least 100% by the preferred retirement age. Any combination of four levers can be manipulated to achieve (or maintain) fully-funded status; savings rate, retirement age, target retirement income and investment risk.

Diversification’s role changes in an asset-liability paradigm. The investment objective moves from risk/return optimisation to matching the nature, duration and variability of retirement liabilities (or needs). For couples this would ideally incorporate differing life expectancies and age pension entitlement.

There is an obvious link here to Defined Benefit (DB) retirement plans, where the provider assumes the risk of meeting a comfortable retirement lifestyle. The challenge is that these plans have been replaced by Defined Contribution plans, and this recent article made the case for retaining some DB features. In the Netherlands, where DB funds still dominate, the average pension fund has an allocation to growth assets of 24%, whilst in Australia it is around 68%. The Dutch objective is to fund long-term retirement cash flows. Australia’s focus remains primarily on accumulating lump sums payments and shorter-term investment returns.

The challenge for the Australian superannuation sector is to move from a ‘to retirement’ mindset to a ‘through retirement’ mindset within a member-centric consumption frame. As Nobel laureate and pioneer of the lifetime consumption approach, Professor Robert Merton, has opined: “sustainable income flow, not the stock of wealth, is the objective that counts for retirement planning”.

Harry Chemay is a Certified Investment Management Analyst who consults across both retail and institutional superannuation, focusing on post-retirement outcomes. He has previously practised as a specialist SMSF advisor, and as an investment consultant to APRA-regulated superannuation funds.