It seems wealth creation has become a dirty joke in Australia. For months, there have been attacks on the money accumulated in superannuation; now Labor, the Greens and even the Reserve Bank have upped the ante by calling for a review of negative gearing.

It’s an attack, not so much on the wealthy, but on middle Australia. Contrary to the spin, Australians who are using negative gearing to increase their wealth are not millionaires flouting the tax system – the majority of them earn less than $80,000 a year and are only buying a single investment property.

Let’s think about a typical couple with secure jobs and earning $80,000 a year each. They are about to turn 50, have just paid their house off, and are well aware there’s unlikely to be much of a pension available to them when they retire.

The options available to them are cash, property and shares. Cash is particularly unappealing, with rates at historic lows and likely to fall further. They are terrified of shares, which they regard as a bit of a punt and are becoming increasingly wary of super, due to the barrage of calls to change the rules.

The only option left for them is property. They are not interested in non-residential property, where vacancies of a year or more are common, so their choice of asset to build a portfolio for their retirement is residential real estate.

They decide to bite the bullet and borrow $450,000 at 5%, secured by a mortgage over their existing home, to buy a property for $450,000. Repayments of $3560 a month will have the property paid off in 15 years when they want to retire.

In Year One, the net income from the property will be $18,000, and the interest for the first year on their loan will be $22,500. Hence they are negatively geared to the tune of $4500 and should qualify for a tax refund of around $1250 each when depreciation allowances are taken into account. The total cost to the taxpayer is just $2500 – hardly the stuff that grand tax schemes are made of.

Now fast forward to Year Five, when their net rents are likely to have increased to $21,000, while their loan is down to $339,000. Their interest deduction for the year is just $16,950.

Lo and behold, they are now positively geared. In fact, the surplus rents may well push them into a higher tax bracket, unless our squabbling politicians have got their act together and agreed to personal tax cuts in that time.

By the time they get to 65, the debt should be paid off and the property could be worth $670,000, assuming capital growth of 4% per annum; producing rents of $24,000 per annum assuming annual increases of 3%.

Let’s hope by now they’re feeling better about their employer-paid superannuation, because they’re going to need it. They’re well outside pension eligibility, but the rents from the property probably won’t be enough for them to live on, particularly with increasing maintenance costs as the property ages. Once they exhaust their superannuation, they’ll be forced to sell the house to provide enough funds to live on. This will generate a hefty capital gains tax bill.

Let me stress that this is not the kind of strategy I recommend – I much prefer the flexibility and growth potential of a diversified share portfolio. However, the couple in question are typical of many Australians in their tax bracket. Instead of being attacked, they should be commended for trying to be self-sufficient, and for the substantial contribution to taxes they will make in the future.

Addendum from the Editor

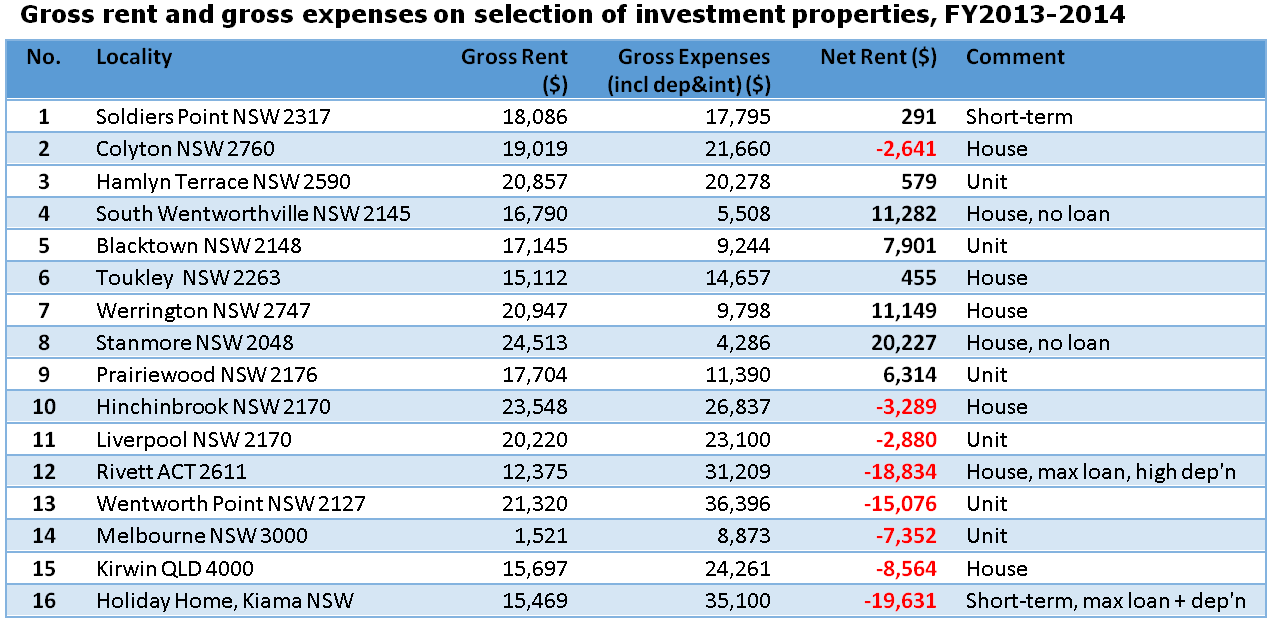

As background to the negative gearing debate, I asked a suburban accountant about his client's income and expenses on investment properties. This practice is a small operation with a few staff in western Sydney, doing basic accounting work in the same way as thousands of other small firms. He sent me the table below.

NW Table1 240715b

Although this is a tiny sample, it shows how different the experiences are. In cases where loans are repaid, there is strong positive net income. But others with maximum gearing, depreciation and interest in advance create sizeable deductions. In most cases, there is either net income or a small deduction.

Noel Whittaker is the author of Making Money Made Simple and numerous other books on personal finance. His advice is general in nature and readers should seek their own professional advice before making any financial decisions. See www.noelwhittaker.com.au.