Changing lifestyles combined with increasing life expectancy have outgrown traditional retirement planning models. But living longer does not translate into financial freedom. The natural conclusion is that you can work longer and therefore have more savings for your retirement. But the paradox is that people have less income-earning years and more education years and a better education does not necessarily lead to an improved financial position.

Increased life expectancy

Over the last 50 years, life expectancy has increased by around 12 years. A child born today will live until they are in their early 90s, and possibly much longer. The reasons Australians are living longer include better diet, improved medicines and living conditions.

In addition to everyone living longer, people are delaying significant life events. Australians are getting married and starting families later and having fewer children. Higher property costs means that children are staying at home longer and this is reflected in the increasing age of first home buyers. Many of these decisions regarding lifestyle are made because of someone’s financial position.

Economic structural changes

There have also been structural changes to the Australian economy that are impacting on an individual’s ability to save and invest for their future. Notably, Australia has increasingly become a high cost of production economy and to compete internationally we must improve our skills and qualifications. Australians are therefore spending more time at school and in tertiary and vocational training at a financial cost to themselves. Even with Government assistance to fund tertiary education many young adults are starting their working years indebted.

Another major structural change occurring is the increasing trend to casual or part time work. Until the early 1990s it was common to have a job with one organisation for life. Today, this is rare and it is expected that people will change not only jobs four or five times in their career, but also the industry. This trend to part time or casual work, particularly amongst older workers, means their pre-retirement incomes are lower, limiting their ability to save.

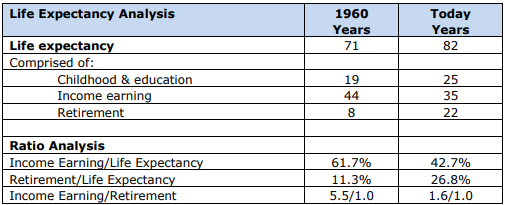

Wealthmaker Financial Services has analysed these trends and structural changes, producing some telling ratios that have implications not only for financial institutions, but every Australian.

Sources: CIA World Fact Book, World Bank, ABS School Statistics Census, Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Averaging has been applied to cover the differences, e.g. males versus females.

The table shows that a person born in 1960 was expected to live to 71, today that person’s life expectancy has been revised to 82. The table then shows how those years will be spent. The table contains three important points for all of us:

1. Income earning/life expectancy

In 1960 the average Australian spent 61.7% of their life working, whereas today it’s only 42.7%. This means that Australians have less time in the workforce, and therefore a reduced timeframe to save and invest for their retirement.

2. Retirement/life expectancy

In 1960 the average Australian was expected to live for 8 years after they retired. Today it’s around 22 years. For many in their pre-retirement years, they are unable to accumulate any more wealth because they are working part-time, even though they may wish to work full time. This means that their income is being used for living expenses.

3. Income Earning/retirement

In 1960, an Australian had 5.5 income-earning years to save or invest for each retirement year. Today the ratio is 1.6 earning years. An individual must save enough during their income-earning years to pay for 22 years of expected retirement.

Another factor frequently overlooked is the increasing tertiary education costs. Even with HECS and VET fee assistance, most children today when they start their working lives are indebted and often have to pay off this debt before they take out a mortgage. This is unlike the baby boomers, many of whom received free tertiary education, so they started their working lives debt free.

As our income-earning years are decreasing and our retirement years are increasing the current level of superannuation savings is insufficient. The Federal Government is taking some action to address this by increasing the superannuation levy, however, this only goes part of the way. Australians will have to work longer and may have to accept a lower standard of living both before and in retirement.

Michael McAlary is Founder and Managing Director of WealthMaker Financial Services.