This is an edited transcript of an interview between Stanford Brown CEO Vincent O'Neill and former RBA Governor and Stanford Brown Investment Committee member Ian Macfarlane.

Vincent O'Neill: Where do you see inflation now versus where we were 12 months ago?

Ian Macfarlane: There has been progress made on inflation, particularly in the U.S. So it peaked at 9.1% and it's now 4.9%, which is quite a big fall. And the reason it's falling is that it's the transitory bits that jumped up, either stopped going up or are, in many cases, falling again, like energy.

But you should look at measures of core or underlying inflation. The most obvious one there for the U.S. is to take out energy and food. If you look at that, it never went up anywhere near as much as the total CPI and hasn't gone down much either. It's running about 6%. So that's a better indication of ...

US core inflation rate

O'Neill: Where true inflation levels are up.

Macfarlane: In Australia, our CPI has gone down a lot less than the U.S. CPI. But we have three different measures of our underlying inflation. Our underlying is also somewhere between 5% and 6% and so really, we've got to think of ourselves as being in a world where underlying inflation is probably somewhere between 5% and 6%.

O'Neill: Certainly quite a bit higher than where the central bankers would want it to be.

Macfarlane: A lot more.

O'Neill: Probably quite sticky at those levels as well.

Macfarlane: I think so, but the market doesn't. This is the interesting thing. The market has been optimistic on the economic outlook. It's also been optimistic on inflation, implicitly, we're not permitted to call inflation because we know that through last year, and it's also the case this year, the market has expected interest rates to go up a bit, but then start coming down within the year.

O'Neill: Cuts before Christmas.

Macfarlane: Early fall in interest rates that could only happen if there was a pronounced fall in inflation and which I don't think is going to happen. In that sense, I think the markets have got it wrong. They're too optimistic on both activity going up and inflation coming down. Some people have used this phrase ‘immaculate disinflation’, a play on immaculate conception. In other words, you can have disinflation without any other bad things happening.

O'Neill: Some magical outcome.

Macfarlane: Yeah.

O'Neill: Very tall scenario. Do you think perhaps markets are reading central banks resolve, misreading, I should say, the resolve of central banks in terms of balancing. How hard they want to go…

Macfarlane: I think they have all the way along. I can remember when we first started putting up interest rates in Australia, there were economists [saying] the cash rate couldn't go up by more than 1.5%. It’s gone up by 3.75%. I think the central banks are more determined than markets give them credit for.

O'Neill: And they are not going to be comfortable with allowing inflation to lead.

Macfarlane: Powell made a speech where he just said quite bluntly, yes, it might cause a recession, but that would be a lesser harm than having inflation just continue entrenched in the system.

O'Neill: It's possibly happened, they didn't act fast enough or strong enough.

Macfarlane: Yeah, they already were a bit too timid at the very beginning because a lot of central banking and particularly academic economists got sucked into this belief between 2010 and 2021 that we had entered a new world of permanently very low inflation, possibly even risks of deflation. And we will be in a permanently low interest rates or in some cases 0% interest rates. That became very widespread, and it was a shock to them how quickly it turned around. Having been caught a little bit behind, they're determined that, as Powell said, he'd prefer to go down as someone who caused a recession than as someone who allowed entrenched inflation to continue.

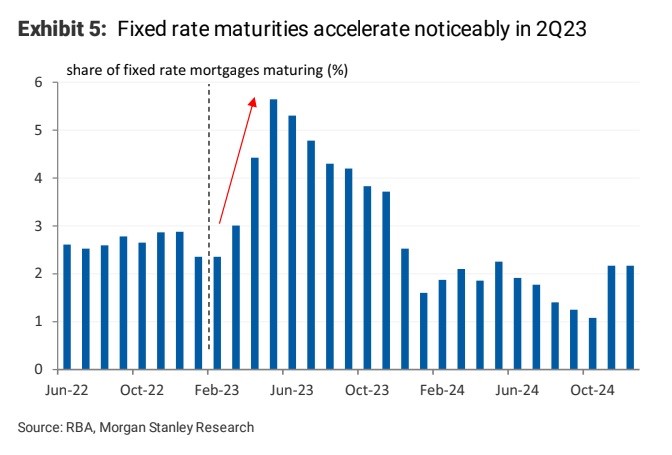

O'Neill: So you paint a picture inflation is sticky, interest rates are higher and will need to remain higher for longer. Maybe we step across and start to think well, okay, what is the impact of this composition, what's the impact on the real economy. And I'm thinking here in Australia, with possible debt levels and we've heard a lot about this fixed rate mortgage cliff that we are on the cusp of. How do you see the outlook, if you were a central banker in terms of the likely impact to the real world?

Macfarlane: We'll work our way towards it. As I said I would have thought there'd been more impact by now. The central question you have to ask yourself is with the increase in monetary policy to date and in my view probably future increases - is it going to bring about a major slowing in economies and possibly recession? I think there is a lot more to come.

O'Neill: Surely it must.

Macfarlane: I mean the adjustment to date has been quite minor. There must be more to come. I think you have to be cautious, you have to say that the markets are more optimistic than they should be, the outcome is probably going to be worse than they think. And how's -- what's the form it's taking? Well, you don't really know how they adjust -- what form the adjustment will take, particularly in financial markets.

Now … the U.S. system where the banks are the ones that are under pressure and part of that is because of the structure of U.S. banks where obviously the deposits are variable. If you want to keep your deposits, you have got to put the interest rates up where competitors are. But so much of your lending book is absolutely fixed in 30-year mortgages, which have been taken out in the ultra-low interest rate period and everyone has got an ultra-low.

O'Neill: No one's rushing to refinance in this environment.

Macfarlane: That’s right. So that puts the pressure on the banks.

O'Neill: They've got lower income from that, but rising cost of capital.

Macfarlane: Yeah. Now in Australia it's the other way round. The banks are in very sound position because both on the deposit side and the lending side, there's variable interest rates. You don't get squeezed. What you lose on one, you gain on the other. But what that means is it puts the pressure on the borrower because the borrower, unlike the U.S. borrower, who sits on their low interest 30-year mortgage, the Australian borrower in most cases is either on a variable mortgage or if it's a fixed rate mortgage, it's only a 3-year mortgage.

O'Neill: So that's the point we're at right now, where the those that were fortunate enough to be on the 2, 3-year fixed mortgage are now coming towards the end of that, and realizing they're heading for rates at least doubling, likely more.

Macfarlane: And the problem is let's say they've got, for arguments sake, an $800,000 mortgage, which is quite common these days. And they're going to have to come to the end of the three years. They’ve got to pay it back. And the idea is you roll it out; you go and get a different mortgage - a new variable rate mortgage, probably to try and pay back the old one. But at this higher level of interest rates, you cannot borrow $800,000. You're only eligible to borrow $700,000 because the servicing costs determine the size of the mortgage. Clearly there's a potential for serious problem there. It'll be resolved by both the bank [and] the borrower taking a haircut, probably APRA [the prudential regulator: ed] have to bend a few rules, and conceivably, in the last resort, the government having to step in because no one wants…

O'Neill: That's quite an extreme situation for the government to step in.

Macfarlane: I think they would.

O'Neill: I think they certainly would if that was required.

Macfarlane: I mean there’s hundreds of thousands of people with fixed rate mortgages that are going to mature, and if half of those were not able to get new funding to pay out their old loan, it would be serious issue and the last thing the banks want to do is just foreclose.

I think the borrower is going to have to pay more if they are coming out of a low fixed rate. They're going to pay a lot more. And quite possibly APRA is going to have to relax the rule that says when you work out how much you can borrow, you've got to assume that interest rates could rise by 300 basis points.

O'Neill: Very sensible rule when rates are 0%.

Macfarlane: That's right. Maybe you don't need as big a buffer as 3%. As I say, I think if it really got nasty, there would have to be some form of additional lending coming from the government.

I think it's the pressure point in Australia and this is the problem. The biggest effect of tightening monetary policy is on anyone who's got a lot of borrowing. And in Australia, that is the household sector.

This is an edited transcript of an interview between Stanford Brown CEO Vincent O'Neill and former RBA Governor and Stanford Brown Investment Committee member Ian Macfarlane.

James Gruber is an Assistant Editor for Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au. This article is general information.