As the drums of war beat ever louder in Korea, many people have asked me about what happened to share prices during the last Korean War. It is a fascinating story as the 1951-52 stock market fall in Australia was the only instance of a major sell-off here that was not accompanied by a fall in the US market. At all other times, we follow the US market up and down.

Australian and US markets diverge

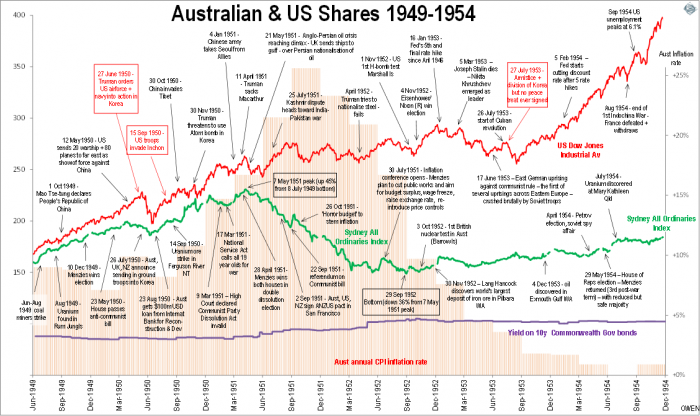

Share prices surged during the early stages of the War but then the Australian market fell by 36% from 7 May 1951 to 29 September 1952 and then rose only very weakly in 1953-54. In contrast, the US market remained strong throughout the War, pausing only briefly at the end of the war in 1953 before surging strongly again in 1954.

Here is a daily chart of the Sydney All Ordinaries Index (green) and the US Dow Jones (red) from the middle of 1949 to the end of 1954.

Please click on image to enlarge.

It was feared that the Korean War may start World War III but it ended in a stalemate in mid-1953 with Korea divided in two, as it remains today. The prelude was Mao Zedong declaring the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949, and the US sending the first war ships and planes as a show of force against China in May 1950, before sending in troops in September. Australia supported the US by also sending in troops.

Other global events

In addition, there were a number of other cold war skirmishes around the world at the time, with the Soviets brutally suppressing uprisings in Eastern Europe, the French losing the first Indochina war, the Anglo-Persian dispute in May 1951, the Kashmir dispute in July 1951 that threatened to reignite the India-Pakistan war, and the start of the Cuban revolution.

The US was testing atom bombs and H-bombs in the Pacific while Australia was allowing the UK to test nuclear bombs here on our flora, fauna and aboriginal population. The threat of communism drove domestic politics in Australia and the US. In Australia, Chifley was trying but failing to nationalise the banks, and was defeated by Menzies. In the US, Truman was trying and also failing to nationalise the steel industry, replaced by Eisenhower. In Australia, we had the Petrov defection and the Soviet espionage affair, and the US had McCarthyist witch-hunts for suspected communists. Everywhere there were union agitation and strikes that were quickly branded as communist inspired.

Why was the Australian market so weak?

Why did Australian share prices fall while US shares powered through it all? The answer is inflation (shown in the chart as orange bars) and the War was only partly to blame. Inflation in Australia was already running at 9% in 1949 and 1950 but shot up quickly to 25% by the end of 1951. It was partly due to the surge in post-WW2 demand as war-time price controls were lifted, but it was made much worse by our centralised wage fixing system that increased wages as prices rose, creating an inflationary spiral. The 30% devaluation of the Australian pound in 1949 (when Sterling devalued and we stuck with Sterling not the US dollar) did not help.

Another major factor was the trebling of the price of wool (our main export earner) as the US bought up all of our wool (and many other commodities) in advance for the War effort, leading to a surge in export revenues. The banks were also to blame, ignoring the regulator’s various attempts to rein in their profligate post-war lending boom. Runaway inflation was only brought back below 5% in 1953 by a combination of savage sales tax hikes, tariff hikes, spending cuts and lending controls.

The differences between Australia and the US were mainly in our domestic policy responses to inflation, not the War itself. The US also had an inflation spike in 1951 but it peaked at 9% and fell to very low levels again (below 2%) by 1952 as the Fed raised interest rates. The Korean War hyperinflation episode in Australia and the deflationary recession that followed in 1953 provided much of the impetus that led to the formation of the Reserve Bank and the short-term money market in 1959 that would allow credit and economic activity to be controlled via short-term interest rates as it was in the US.

What might the future hold?

First, war is usually a disaster for investors on the losing side – their assets are generally confiscated, their debts are repudiated, companies are expropriated and ownership rights in shares, bonds and property are confiscated. Examples include: the Paris Bourse after the Waterloo loss, Confederate bonds and shares after the American Civil War, St Petersburg stock market after the Russian Revolution, the Shanghai stock market after the Chinese Revolution, Berlin and Tokyo shares after WW2, Saigon shares after victory by North Vietnam, etc. The victors take everything and impose their own new laws.

So, if you believe the next Korean War will lead to Australia being invaded, occupied and subsumed by China with all privately-owned assets confiscated (as Mao Zedong did when he won the revolutionary war in China in 1949) then you should probably sell all your assets while there is still a free market for them. But the chance of Australia being invaded and absorbed into a greater Communist China any time soon is approximately zero. Even when China absorbed Hong Kong in 1997 and Macau in 1999, private commercial interests were retained and indeed flourished.

Otherwise, wars and rapid military build-ups are generally good for business. Commodities prices skyrocket because demand suddenly accelerates as the government buys up everything for the war effort. Governments often control prices (and perhaps share prices) to prevent excess profiteering. Even in Australia’s darkest year in WW2, 1942, with Japanese bombs raining down across Northern Australia after the fall of Singapore and with Sydney Harbour bombed by Japanese subs, Australian shares returned 18%, or a healthy 9% after inflation.

Since the GFC, every central banker in the world has been dreaming about how to revive inflation, and they are fully aware that military conflict is the only sure solution. As military build-ups escalate in China, the US, Japan and Russia, central bankers are likely to allow inflation to rise for a while before taking steps too little and too late to bring it back under control.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at privately-owned advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.