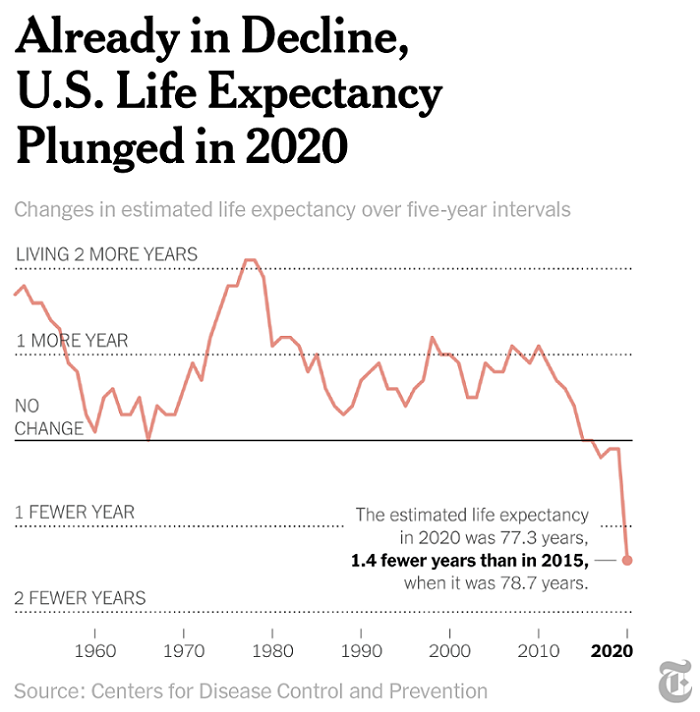

The New York Times headline screamed 'US Life Expectancy Plunged In 2020' on 21 July 2021. The sub-headline continued: “The 18-month drop, the steepest decline since World War II, was fueled by the coronavirus pandemic.” Specifically, life expectancy was reported to have declined from 78.8 years to 77.3 years.

This is such a big deal that The Times (of London) also headlined it: “Life expectancy gets even shorter for Americans.” They added that “Covid-19 was blamed for three quarters of the decline.”

What does the headline even mean?

Really? So all Americans expect to die a year and a half earlier than before (on average, of course)? That’s what the headlines mean, right?

No, not really, but the truth doesn’t make for as dramatic a headline. And if you can get an attention-grabbing headline, who cares if it isn’t accurate?

The true meaning of the statistics was, actually, reported accurately later in the New York Times article:

“If American children born today spent their entire lives under the conditions of 2020, they would live an average of 77.3 years, down from 78.8 in 2019.”

See the difference? If Covid-19 stays around in as virulent a form as in 2020, with no vaccinations or other defences against it, then … yes, future life expectancy will indeed fall.

I went to the actual report from the (US) National Center for Health Statistics (a part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), and it was very clear:

“The period life table does not represent the mortality experience of an actual birth cohort but rather presents what would happen to a hypothetical cohort if it experienced throughout its entire life the mortality conditions of a particular period.”

Which is jargon for what I said in the previous paragraph.

A misunderstanding of life expectancy

Why does this bother me? Because people misunderstand what life expectancy means. I’d greatly prefer it if it were instead called ‘the average survival age’, trying to avoid the macabre feelings that anything involving death can create. And what’s a ‘cohort’ anyway?

Let me explain.

A cohort is a group of people with a specific characteristic in common. When dealing with longevity, cohorts are usually defined by age and gender. For example, 'all female children born in 1970' or 'all males now aged 55' – that sort of thing.

‘Life expectancy’ means the average expected age to which members of the cohort in question will survive. ‘Expected’? There’s nothing expected about it. It’s a jargon word that means it’s the average of a distribution (perhaps even a very wide distribution) of possibilities.

For example … What does it mean if the life expectancy for people of your gender and year of birth is stated to be 80 years? It means that, if you look at all the people in that cohort (your gender, your year of birth), they will have a wide range of ages to which they will survive, and roughly half are expected to survive to some age short of 80 and roughly half to some age beyond 80.

That’s interesting, because the number is often (wrongly) interpreted as the expected limit of life, as if (in that example) 80 is the maximum age any of that group can be expected to reach. No, it’s not the maximum: it’s the average. There’s a 50/50 chance of outliving it.

It's higher for older people

Now here’s something that is even more often misunderstood. Suppose we subdivide that original group and now include only those who are still alive at age 50. What’s their likely average survival age? Is it still 80? No, it’s bound to be higher than 80. That’s because some of the original group have already passed on, before age 50. They brought the average down. The average for the group of survivors is therefore higher than 80. It might, for example, be 83.

That’s right, the definition of the cohort, the group, has changed. It’s no longer all of those who were born in your year of birth. It’s now limited to those who have survived beyond age 50. That’s a different group, even if the members of the (smaller) ‘survived to 50’ group were also part of the original ‘born in the same year as you’ group.

It’s like starting with ‘all people in the world’ and then changing to ‘all females’: the second group is different from the first one, even though all members of the (smaller) second group are also part of the first group. That’s a subtle distinction that the vast majority of people are unaware of.

Similarly, those who survive beyond age 60 have an average projected survival age even higher. And so on. The older you are, the higher the average projected survival age.

One final rant on the way this ‘life expectancy’ was calculated. You’d think, since it deals with future survival, that it would reflect the possibility of improvement in health, the sort of trend that we’ve been used to for a couple of centuries. Of course you can never get it right, because it would require a crystal ball. And, to put it mildly, that’s impossible to find.

But what they’ve found isn’t a crystal ball, it’s a rear-view mirror, and indeed it only shows the immediate past.

Which brings us back to the headline.

There are potentially three aspects of it that are capable of misinterpretation.

First, the numbers only apply if Covid-19 (with no vaccination) and all other mortality-related conditions (including, for example, the opioid crisis) prevail forever.

Second, even when adjusted to reflect a probably more-promising future, the numbers don’t reflect the maximum age one can reach. Roughly half of us should outlive the stated expectancies.

And third, they apply only to newborns. The longer we survive, the higher the average age to which we will eventually survive. It's common sense when it’s expressed that way, isn’t it?

There! Even with such a morbid subject, I bring you nothing but good news!

Don Ezra, now happily retired, is the former Co-Chairman of global consulting for Russell Investments worldwide, and the author of “Life Two: how to get to and enjoy what used to be called retirement”. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.