It’s becoming unavoidable. Private markets investors on average make more than public market investors, and the worldwide trend towards privatisation of everything makes it likely that this will continue to be the case.

The higher returns of private markets investments may be a product of private investors achieving disproportionately high returns while a company remains private, and using the public equity market to monetise these gains (at the expense of public market investors). This could lead to a future where an individual investor in public markets may find future returns increasingly squeezed downwards by private markets, whose returns are accordingly higher.

The object of this article is to develop a basic private markets portfolio plan for an individual investor, with a focus first on avoiding basic mistakes, or lemons. Because private market investments can have a fundamentally different liquidity profile from public market investments, they present more challenges. Most can be resolved using the same tools applied to public markets, but with alterations. These are shown below.

The allure of private markets funds

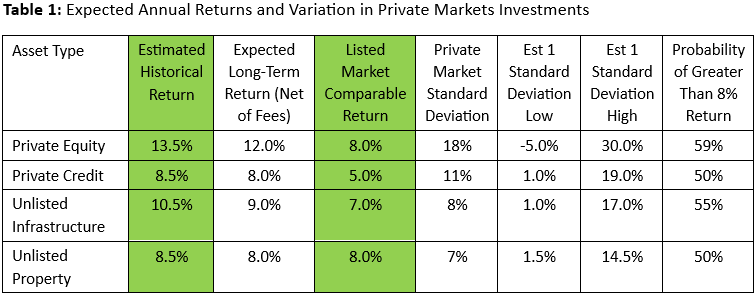

Table 1 shows the estimated annual returns and return ranges for the big four categories of private markets investments for Australian investors. The estimated data shows that private equity funds have the highest expected return and return range, property funds have the lowest, while private credit and unlisted infrastructure funds are in the middle.

Sources for private markets data: Click here.

The variation in private market returns is as important as the returns themselves. Table 1 also shows the return ranges based on one standard deviation from the expected return (i.e., two-thirds of the total return range), as a guide to what an investor in a limited-liquidity fund might expect. Even though the one-year return range for listed equities is much higher than for closed-end private market funds (MSCI World long-term annual volatility is 15%), the effect of private market fund volatility is more significant for a long-term investor, especially one with a limited number of investments. In simple terms, there are lemons in private markets investments, just as there are in individual stock and bond investments, but it is more difficult to avoid them in private markets.

Even a good manager may have one or more underperforming funds, and it is almost impossible to know in advance whether a fund will be a lemon.

Private markets and quasi-private markets investments

Both global and Australian private markets (where investors can buy and sell private assets off-exchange) are fast becoming a reality for individual investors. Investment in listed private market investments is one option. There are a growing number of listed investment companies and listed investment trusts that provide tradeable vehicles for private market investments. In Australia, however, these have generally tended to develop a discount to net asset value. They are also likely to have relatively high correlation with listed equity indices. Neither characteristic is ideal for a private markets investor. And while it is in theory possible that a group of investors in such listed private markets investments could seek to de-list the company and take control of the investments themselves, in most cases these are direct investments not in listed companies, but in long-term funds controlled by the investment managers themselves.

Investment selection and timing risk

Because listed private markets securities tend to develop a NAV discount over time, open or closed-end funds seem like a better option as investments. Obtaining investment access directly to funds whose actual value in most circumstances[1] corresponds with their market value is not as simple as buying a listed investment company’s shares on an exchange.

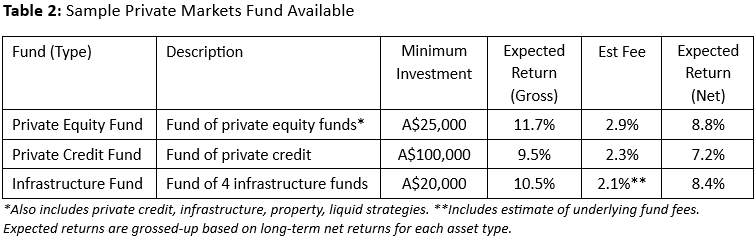

Of the two options, open-ended funds are preferable for non-institutional investors due to their liquidity. Table 2 shows some anonymised sample investments that are available to wholesale investors in Australia. Each are semi-liquid, open-ended funds that provide periodic, limited liquidity to investors.

Ideally, a global and/or developed market fund is preferable. The funds shown in Table 2 are all global-focused funds that invest in offshore private assets. Long-term expected returns are higher than those of listed private markets funds, but have additional fee drag compared with the net returns available to institutional private market investors. Investors also give up some liquidity compared with listed private markets vehicles, with liquidity generally available only quarterly, and up to discretionary amounts.

Developing a portfolio plan

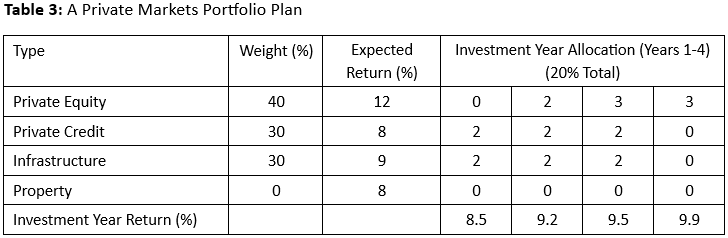

Once investment types have been selected, the next step is to choose actual investments.[2] Table 3 shows a dollar cost averaging portfolio plan for a new investor in private markets with a moderate risk tolerance. Dollar cost averaging historically has been applied to listed equity investing, but because of the illiquidity and variable fund performance of private markets, it is arguably even more applicable to private markets investing. As applied to private markets, this plan ideally means investing not only in different years, but also in different funds or instruments each year (including listed investments, if suitable open- or closed-end funds are not feasible), in order to increase diversification.

Alternatively, if an investor can identify suitable open-end funds for each strategy type, the plan could allocate to the same open-ended fund in each asset type gradually, similar to the way an active manager may incrementally allocate to specific stock investments. The portfolio plan below could have nine different investments, or it could have three investments, one of each asset type.

Dollar cost averaging into a diversified private markets portfolio requires more planning than just making regular contributions to an equity portfolio, but it is the most sensible when faced with the multiple risks that private markets pose to ordinary investors. At its end point, a fully diversified private markets portfolio will tend towards the average return of each of its components, making it index-like. The diversification benefit more than compensates for an average return.

Horizon analysis

Because they have adverse selection risk and require fairly continuous vigilance, private markets investing is not easy: public market investing has the advantage of simplicity, and fees for most index investments continue to decline. But as most of the developed world continues to privatise with no end in sight, and more investments in private markets become available, ordinary investors should consider investing, as long as they can do so with a logical strategy. While historical and – if the privatisation trend continues – future investment returns are likely to be higher for private than public markets, return variability is also high, and in illiquid funds is a real threat to performance. With a systematic investing approach, an investor should be able to avoid, or at least significantly diminish, the risk of investing in private market lemons.

John O’Brien is a Principal Adviser at Patrizia AG. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

[1] Secondary market values can also diverge from stated values, but unlike LICs or LITs they tend to close up over time, rather than expand.

[2] Again, assuming that more types of fund investments without NAV drag become available. Based on the rate of change this is likely.