With the election complete, retirees around the country have claimed victory in opposing Labor’s ‘retiree tax’ on franking credits. Zenith suspects that this may come as cold comfort to those who had already repositioned their portfolios in an attempt to front run the proposed changes given a Labor win looked likely.

During the course of the election, many questions were raised, including:

- What is the future of Listed Investment Companies (LICs)?

- Would legislative changes herald the death of the company structure?

- Should LIC investors consider seeking yield from other asset classes or investment structures?

The Labor impact on LICs

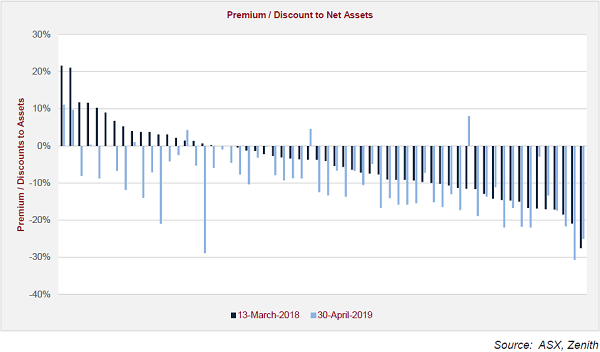

Looking at LIC trading as an indicator, market sentiment experienced a decline post Labor’s announcement on 13 March 2018. When measured by their prevailing premium or discount to NTA, the LIC market materially de-rated as investor uncertainty took hold.

Obviously, Labor’s announcement was not the only aspect at play, as the market had already been de-rating some LICs trading at high premiums to NTA (some trading at 20%+). However, the political impact was a factor, particularly given Australian equity LICs had the largest premiums prior to Labor’s announcement.

The following chart highlights this change by comparing each LICs/LITs prevailing premium or discount to net assets as at 13 March 2018 (when Labor’s policy was announced), compared with 30 April 2019. [Note: we have elected not to label each vehicle as this is less about the individuals and more about the broader trend].

Click to enlarge

With Labor losing to the Coalition, we expect some level of positive re-rating for some of the LICs/LITs. However, this raises other interesting questions.

In the run up to the election, many commentators thought Labor’s proposal would ultimately address retirees' strong home bias, as it meant people would effectively be encouraged to diversify away from portfolios traditionally heavy in fully-franked equities as a source of yield.

But, with investors having just passed through a politically driven near-death experience, how might the search for yield change? Will LICs investing in Australian equities remain attractive as an investment tool?

Zenith believes there are two essential elements to consider: the return characteristics of asset classes and the structural differences of utilising a company versus a trust.

Where’s my yield?

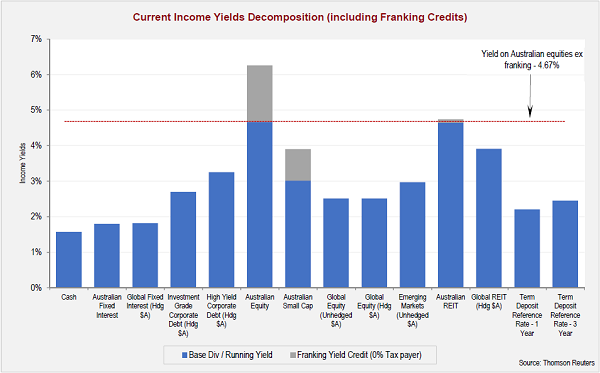

Prior to the election, the question uppermost in the minds of those who stood to lose franking credits (i.e. 0% tax payers) was where to find replacement income. The realistic answer is that this was not easily done without making major compromises to asset allocation.

[Note that for the purposes of this report, we are not considering other structural avenues such as changing to industry funds].

The following chart summaries current yields available from various asset classes as at 30 April 2019.

Click to enlarge

Australian equities have traditionally been a high-yield investment. While this has been driven in part by the taxation perspective, Australians have long expected to derive income from equities. However, even when removing the impact of franking credits, Australian equities are still one of the highest-yielding assets classes which are available in a liquid, diversified format.

While listed property in the form of Australian REITs runs a close second when removing tax implications, a major shift into REITs is unlikely to be conducive to adequate risk management and portfolio diversification. In sidestepping the franking issue, other investment risks come into play.

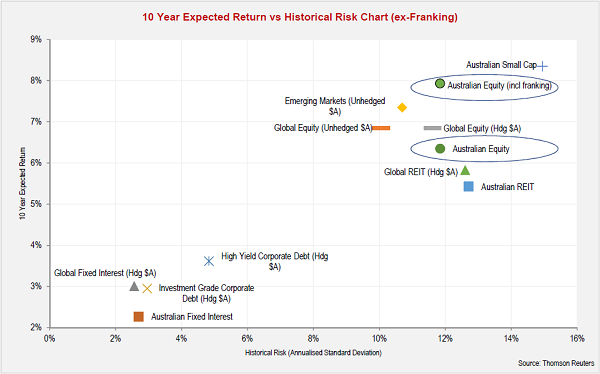

Based on Zenith’s long-term market assumptions undertaken by our portfolio consulting team, the long-term expected returns versus their historical risk levels is shown in the chart below for the major liquid asset classes.

Click to enlarge

From a portfolio construction perspective, lowering the returns available from Australian equities by removing franking would have reduced their allocation in portfolios from an optimisation perspective (the impact of lower returns for the same risk). While feasible, this has two glaring outcomes. Firstly, substituting other assets classes simply introduces other risks and secondly, it still fails to address the question of replacing income for current retirees.

Investors could also invest in other income-producing securities. Some private markets such as real estate, infrastructure and credit can also deliver stable yields at attractive levels. However, is that the right move? Ultimately, Australian equities still hold a key position across the asset classes from a yield perspective.

For LIC’s, it would be reasonable to expect that this will continue in the foreseeable future. So, the next logical question is, does the structure of listed vehicles have a bearing on income generation?

LICs or LITs? Which works best?

The rise of Listed Investment Trusts (LITs) has been a relatively recent phenomenon, brought increasingly into focus as the arguments around franking mounted. The key difference between the two structures is the way income and capital gains are treated.

For LICs, under the company structure, dividends and capital gains are treated as income, contributing to the profit and loss position. The company pays tax on earnings and pays dividends (franked or unfranked) at the Board's discretion. A company can elect whether to pay dividends and can smooth cash flows using retained earnings from one year to the next. The company may chose to decrease the volatility of the income stream to investors. This has traditionally been a highly-attractive feature of LICs when dealing in an inherently volatile asset class like equities, provided the earnings (retained or otherwise) are there to fund dividends.

As trusts, LITs distribute all net income in the year received, along with any realised capital gains on a pre-tax basis. The investor is liable to pay tax. As a result, LITs pay no tax and therefore have higher cash earnings to be paid out. However, their income streams are more likely to be unpredictable, fluctuating with the manager’s investment activity. While LITs do have the ability to offset these fluctuations somewhat through returns of capital, there is still less control compared with LICs.

Zenith believes that the key determinant of the preferred structure for managers is the asset class, investment strategy and objective. For Australian equities managers, particularly those with high levels of portfolio turnover, a company structure is arguably more conducive to the generation of a stable dividend stream to shareholders.

For asset classes where income generation at the security level is more predictable, such as fixed income, or where assets or strategies tend to generate less income, such as global equities, a trust structure may be more attractive.

Given the position of Australian equity LICs in generating stable dividend streams from an asset class with comparatively high volatility, Zenith believes the LIC structure will continue as a core part of the listed investment market.

However, despite a Coalition victory, the issues around the cost of imputation to the government remains a moral hazard. Zenith believes that all investors, regardless of their current position on the road to retirement, must be cognisant of the consequences of political risk to their portfolios and ensure where possible that adequate planning for flexibility is undertaken.

Dugald Higgins is Head of Property and Listed Strategies at Zenith Investment Partners. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual investor.