We’ve all walked by restaurants and assumed they were ‘good’ based only on the number of patrons inside. It's a common and recurring trait for many of us, so it’s not too surprising how we often assign quality in investment choice by historical returns, further backed up when we see fund flows directed towards such historically well-performing funds. Others are investing, so it must be good.

But sadly, this is a misinformed judgement about the prospects of fund managers, a mistake equally made by investors, regulators and rating agencies.

Watch for mean reversion

While marketers love fund manager and super fund awards, I’ve yet to meet a fund manager who loves them. Accolades based on historical results cannot anticipate a forthcoming force greater than nuclear fusion: mean reversion. As I used to tell my clients, I’ve yet to see a pendulum swing just halfway.

No investment nor actuarial book endorses picking investments based on historical results. On the contrary, marketing always finishes with a 'past returns do not predict future ones'. Yet this hasn’t stopped the creation of ‘heat maps’ or delivering fund awards.

In the early 1980s, one academic report showed how an equally-weighted portfolio of the 43 ‘excellent’ companies listed within Waterman and Peter’s “In Search of Excellence” book had underperformed over a 5-, 10- and even 20-year basis subsequent to the book’s release.

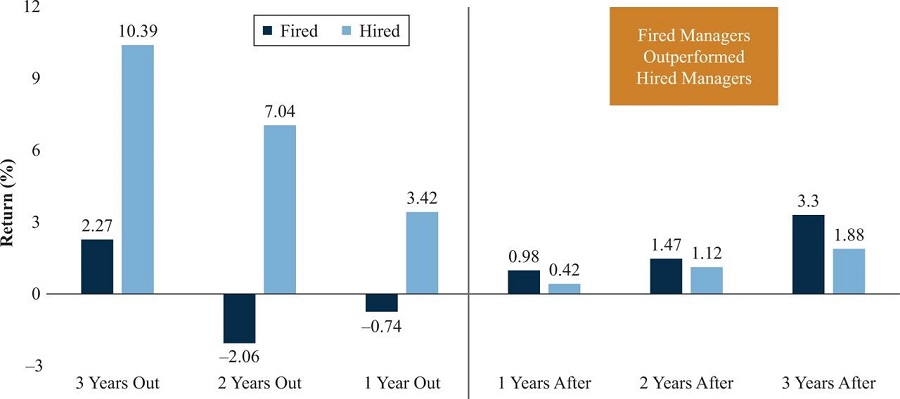

A recent study published in The Journal of Portfolio Management [April 2020], showed how pension funds which have invested with strong-performing managers have lagged those fund managers terminated for underperformance over the same period. While we may find comfort from heat maps and fund awards, their efficacy in predicting future returns is unproven.

Exhibit 1: Before and After Returns of Investment Manager (8,755 hiring decisions over 10 years)

Source: The Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 46, Issue 5

Not making a case for passive index funds

Be assured that I’m not endorsing passive allocation. I hate the term ‘passive’ as it wrongly implies neutrality against active manager selection risk. Choosing between active or passive is itself an ‘active’ decision. Even passive portfolios have their own risk/return characteristics. For example, a high factor weighting towards price momentum can often hold sector weightings far from the actual representation of companies within the broader economy.

As with any portfolio construction rule, every selection must take into account how it contributes to the final risk/reward characteristics on the total portfolio. In every risk statement I’ve ever read, ‘balanced funds’ are described using an absolute return target expressed through:

- CPI+

- One in # years of negative returns

- Maximum drawdown (fall in value)

- BUT NOT on some relative peer ranking over a historical finite period.

Careful what you wish for on consolidation of funds

Just as we don’t drive our cars by looking through our rear-view mirrors, constructing a pension fund based on peer rankings, asset size, Management Expense Ratios and heat maps is a gross misrepresentation as to what we tell members in our risk statements.

When we read media or regulator criticism of a fund for underperforming, be mindful that tomorrow’s praise may be on the same fund they’re criticising today (and vice versa).

Regulators are also pushing for super fund consolidation, especially among the so-called underperformers. Perhaps I’ve been watching too many conspiracy movies on Netflix during lockdown, but my fear is that once we are down to six to eight mega funds, and a systemic failure happens (not if but when - the challenge is the size), superannuation will be nationalised along the lines of the six Swedish National Pension Funds. After all, Direct Contribution (DC) retirement savings is founded on a belief of 'caveat emptor'.

Were a mega fund to fail, it's highly unlikely that the government would not bail them out, thereby compromising the principle that each member is responsible for their own retirement funding. The metrics used to regulate funds have nothing to do with what funds proclaim are their objectives (as listed above: CPI+, max drawdown, etc.).

Lest we forget, the Government allowed members to drawdown on their super at the very bottom of the market cycle in 2020 (instead of, for example, moving it into a loan agreement). I can’t help but wonder who is advising the Government on superannuation based on the 'sell low, buy high' policy.

In fact, each superannuant has varying actual returns (given their varied entry points) and differences in when individuals plan to retire. I believe the one-, three- and five-year snapshots we see in performance reports should be the furthest thing from how we manage the risk/return profiles of funds. When we win awards, we seem vindicated, but when we mean revert, we disregard the low relative ranking.

I find it sad how our gatekeepers and regulators (speaking as a former member of both groups) fall back on probably the worst measure and construct fancy-named agency ranking metrics such as heat maps. Such rankings tell members next to nothing about what their retirement savings will deliver.

Rob Prugue is Principal Consultant at Callidum Investment Research Pty Ltd. He was Senior Managing Director and CEO at Lazard Asset Management (Asia Pacific) for 15 years until March 2018. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.