There is an old saying that when you are up to your knees in alligators, it is hard to remember that the original plan was to drain the swamp. In 2021, that swamp is the COVID-19 pandemic.

But the developed world has been thinking in shorter and shorter timeframes for some decades now, and some things like climate change are starting to tell us we have to take a longer view.

The increasing focus on the short term

So, this article is about standing back and taking a longer view of economic and financial issues, mainly in Australia, although a lot of the observations apply to the developed world at large. Just why is the western world into short-termism and slowing in resolve, and growth?

There are many reasons:

- Relative world peace for some 75 years has led to a lower need of a re-building catch-up following wars, depressions and recessions which none of us want to repeat.

- The well-off countries (in the OECD) are less hungry for growth than poor and emerging nations.

- Productivity in the post-industrial infotronics age of services and technology is not matching the productivity growth of the previous industrial age of goods and electricity and telephony.

- The new political dialectic of Rationalism versus Emotionalism (gut feel) is seeing the latter winning.

- National and state leadership across the world is at levels similar to the 1930s (dictatorships, saber-rattling, fascism, corruption, short-termism or incompetence) and becoming rife.

- Climate change is demanding preventative and alternative measures to avoid global catastrophes, that will slow many economies’ growth for some decades.

Australia's long-term economic growth

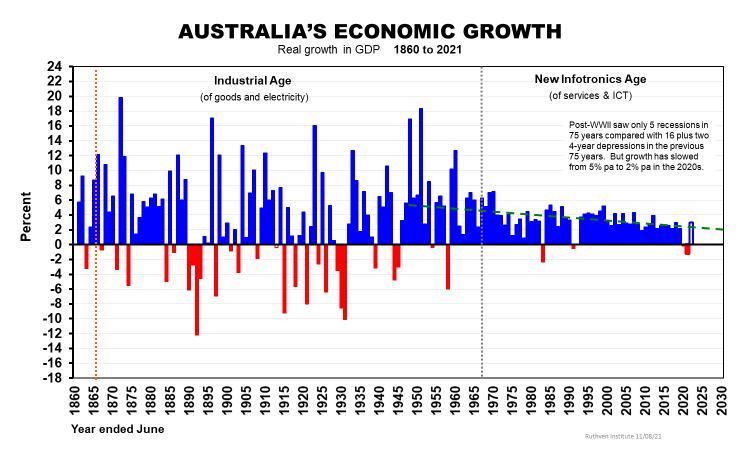

Australia’s growth over more than one and a half centuries is as good as anywhere. We can be thankful that in the post-WWII years, economic growth has been less lumpy, with fewer recessions and no depressions.

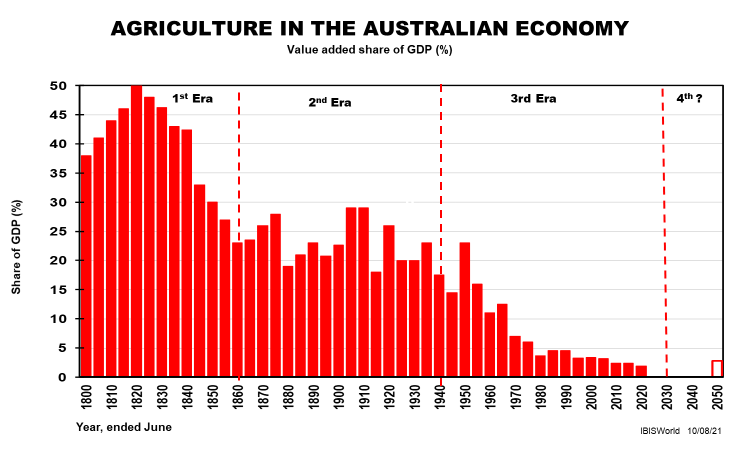

The absence of recessions is mainly due to agriculture shrinking from 20% of our GDP to 2%, thereby removing the recessions caused by droughts, floods and low export demand. Modern fiscal and monetary management helped avoid depressions, and some recessions.

But our economic growth has slowed from 5% pa in the 1950s to 2% pa in the 2020s.

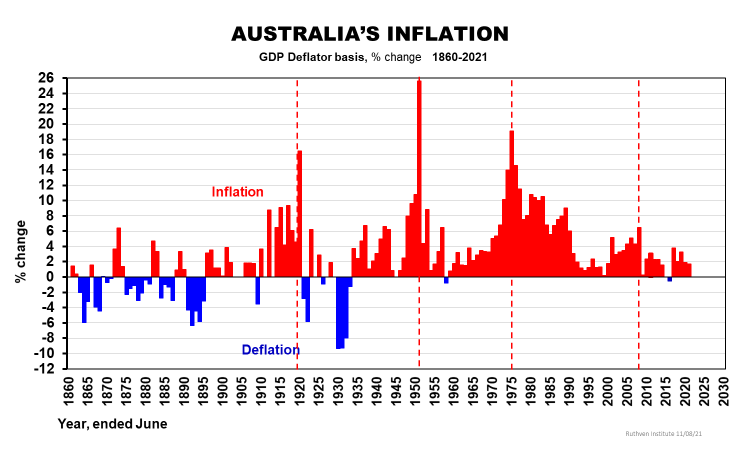

Inflation was non-existent (averaged over any decade) for 217 years to WWI due to the Gold Standard. Since then, we have had four inflation cycles - unevenly - with average 25-year cycles, as we see below. The peak of the current fifth cycle is probably not due till later in this decade, perhaps into the early 2030s.

In turn, inflationary cycles create interest rate cycles, at least in real terms as we see in the next chart.

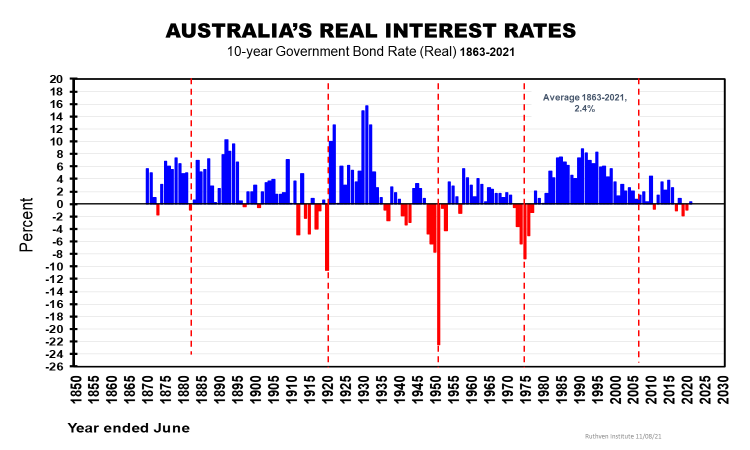

Focus should be on real rates

As we are regularly informed by our RBA Governor, we need not expect nominal interest rates let alone real rates to rise anytime soon. But, when we hear interest rates are at record 'lows', it’s not true. There have been 20 individual years when real rates have been much lower than recently. And the average real bond rate has averaged 2.4% pa for 160 years compared with an average 5.5% pa in nominal terms over the same time frame.

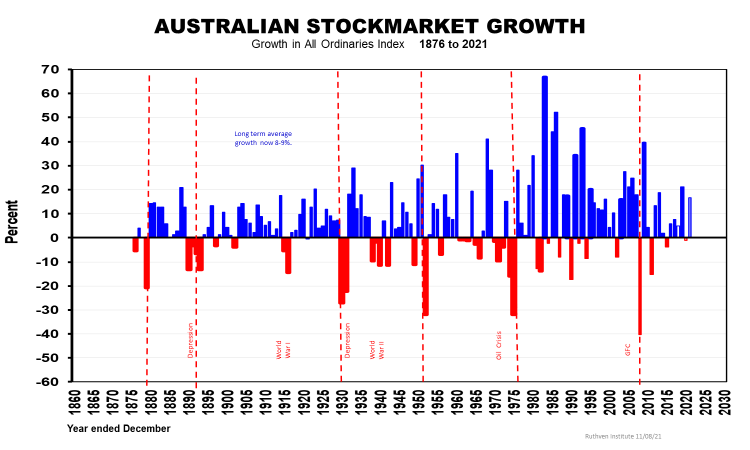

Then there is the sharemarket as measured by the All-Ordinaries Index over a century and a half as we see below.

What stands out is the extraordinary volatility over eight decades from the 1930s depression until the GFC in 2008-09, when deviations of ±30 to 60% were common. That said, there is no saying it won’t happen again with Price/Earnings ratios in some stockmarkets of over 40:1.

Australia has not gone that far into the stratosphere, fortunately, so we may experience less volatility when the next (inevitable) corrections come. There is a prima face average cycle of some 30 years at play, but of unequal lengths, so the next wide gyrations - if we get them at all - are due around the turn of the decade, or soon after.

Industry divisions: mining and agriculture

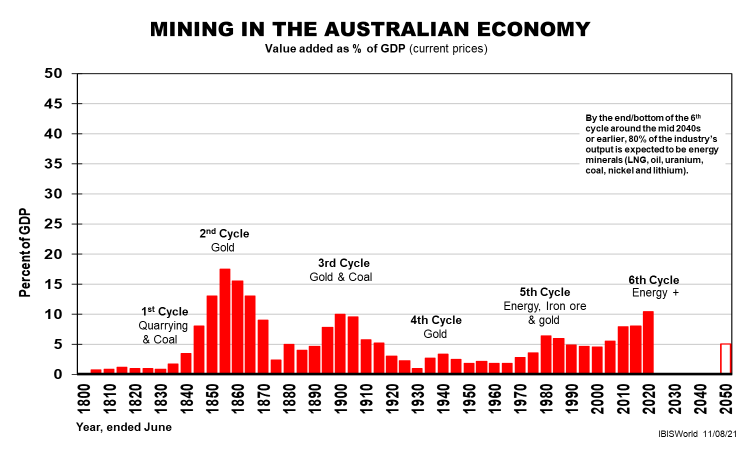

Then there are long cycles in the nation’s 19 industry divisions. The two industries that have dominated our exports for the past 233 years since British settlement (or 'invasion') are mining (our first export ever as coal was backloaded) and agriculture.

In 2021, however, agriculture has shrunk to just 2% of our GDP and around 5% of our exports, having dominated our total exports for most of the first 200 years. Mining now accounts for over half our exports although likely to be half that within 15 years or so.

They remind us that our industries run in cycles too when measured by their contribution to the nation’s economy (GDP). They are very different in their lifecycle lengths and peak shares of GDP, as are the other 17 industry divisions that make up our $2 trillion GDP these days.

Taking a long view creates much-needed perspective

We need longer-term vision of the sort we once had, and the sort that is now in evidence in fast-growing emerging markets, most which are in our own region - the Asia Pacific, headed by China - and in our mega-region of Asia including the Indian sub-continent, headed by India. Perhaps getting rich has made us soporific. Time to wake-up to the operational and competitive challenges as well as the fabulous opportunities.

Phil Ruthven AO is Founder of the Ruthven Institute and Founder of IBISWorld. The Ruthven Institute was created to help any business that wants to emulate world best performance and profitability using the Golden Rules of Success, based on over 45 years of corporate and industry analyses and strategy work.