Last week, the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) released its first Budget Explainer on ‘How super is taxed’. The PBO’s role is to improve transparency around fiscal and budget policy issues, and no doubt there are several superannuation specialists among its 44 staff. The Superannuation Guarantee (SG) system is now over 30 years old, super holds $3.4 trillion or 150% of GDP, and it is both a major source of revenue and a major cost due to tax concessions, depending how it’s viewed.

Why issue a paper now? Because super is too big to ignore, and the Government is looking for savings, as evidenced by the new $3 million tax. The PBO says:

“From a fiscal perspective, super is an important source of Australian Government revenue, accounting for around 5% of total tax revenue in 2021-22. This is the fifth largest source behind personal income tax, company tax, goods and services tax (GST) – which is passed to the states and territories – and customs and excise duties.”

In Treasury’s Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement (TEIS) 2023, the three top tax expenditures are

- Income tax deductions for personal and business income taxes

- Capital Gains Tax deductions

- Superannuation concessions

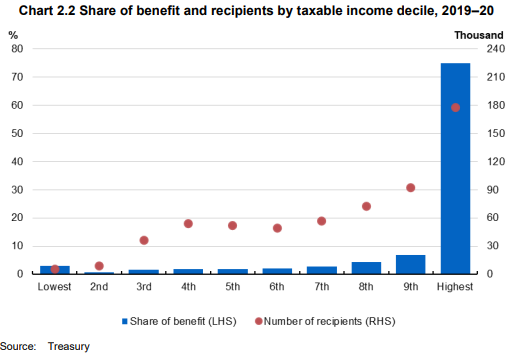

Treasury estimates a cost of revenue foregone due to concessional taxing of superannuation at about $25 billion a year, with almost three-quarters of the tax savings going to the top decile of taxable income earners. Of course, this is the case because these are the people who pay the most tax so any concession will be worth more to them, but it is ammunition to cut back on concessions to high income earners.

Some highlights from ‘How super is taxed’

A check on the wording and emphasis in the PBO Report shows where the Government and its advisers may be looking when considering ways to save on superannuation concessions.

Here are six highlights from the Report.

1. Australia’s taxing of retirement savings hits earlier

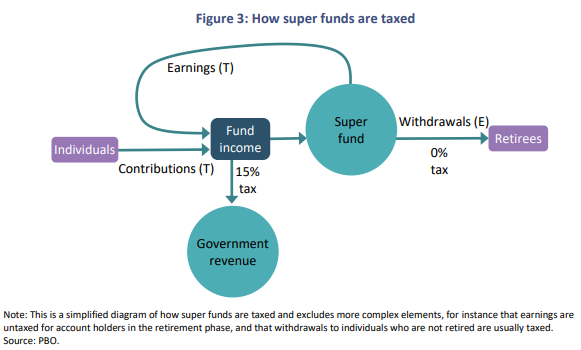

Superannuation can be taxed at three different points:

- When contributions are made into a super fund

- When super fund assets earn investment returns (earnings)

- When withdrawals are made from a super fund.

If each taxing point is denoted as either ‘T’ for Taxed or ‘E’ for Exempt, Australia is said to have a ‘TTE’ super tax system. Contributions and earnings are taxed, while withdrawals are untaxed after a qualifying age. Unlike most OECD countries, Australia taxes earnings on super during working lives rather than when pensions are drawn after retirement.

The crucial point is that contributions made earlier in life are hit by taxes more than those made closer to or after retirement due to the impact of compounding over time. Australia’s taxing of contributions and earnings also raises revenue sooner than taxing withdrawals.

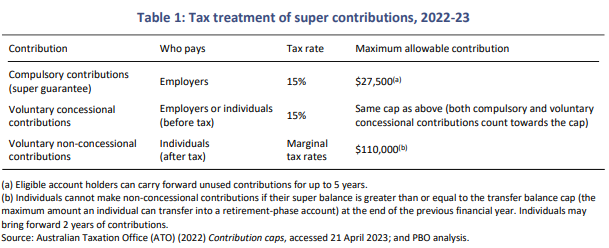

2. Some contributions are taxed at marginal personal rates

It is often assumed that all super contributions are taxed at concessional rates, but there are three ways to contribute to super:

- SG contributions, made by employers

- Voluntary concessional contributions, made by employers or individuals

- Non-concessional contributions, made by individuals.

This third method sources super from after-tax income, and tax at full personal rates has already been paid. For many people with large balances, because concessional contributions are capped at $27,500 a year, it is the non-concessionals which create the high balances, and they have already been heavily taxed. This should be recognised more when large balances are targeted and criticised.

And those earning more than $250,000 (inclusive of their contributions) are subject to Division 293 tax, an additional 15% on contributions.

3. Large funds cannot calculate tax for members with over $3 million

Judging by comments received from many readers, there is little understanding of how a large fund with both pension and accumulation members calculates tax. The PBO explainer demonstrates why the $3 million tax is designed in such an unusual way.

Large super funds know which of their members hold pension funds and which are in accumulation funds, and both are invested in the same pools. But they do not know which members hold more than $3 million in total super balances, and have no way (currently) of imposing the additional 15% on these large balances.

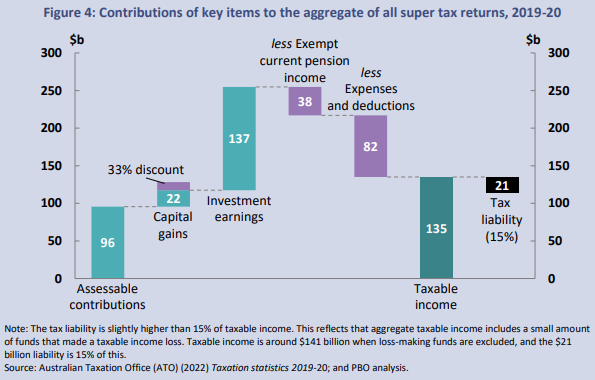

A super fund’s tax return includes all fund earnings and then subtracts the earnings applicable to pension accounts, which are tax free. The most volatile earnings sources are generally capital gains and foreign exchange gains and losses, with dividends and franking credits usually less volatile, depending on large share buyback activity. Net capital gains receive a 33% discount for gains on assets held for at least 12 months.

In the example below, the tax liability of super funds was about $21 billion but the super funds themselves paid only around $11 billion as half of the tax liability was paid in advance by companies paying franking credits to the funds. This is a good summary of what is happening with the super in industry and retail funds.

4. Super tax concessions vary significantly by income

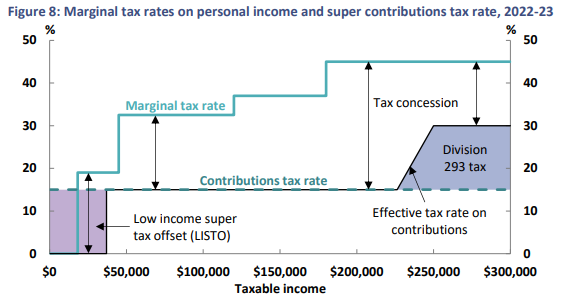

The PBO provides a handy chart to determine which taxable income bracket receives the most concessional treatment versus personal marginal tax rates.

Everyone with taxable income from $37,000 to about $225,000 pays the same tax rate of 15% on concessional contributions, but the sweet spot for most benefits is $180,000 and $225,000, before the Division 293 tax starts kicking in.

Source: PBO, see page 12 of Report for more details

PBO gives an example of the benefit of super to high income earners:

“For instance, an individual who earns $200,000 in 2022-23 faces a marginal tax rate of 47% (including the Medicare levy). If a dollar is paid to this individual’s super fund, the super fund pays 15c of tax on their behalf. If that dollar was instead paid to the individual directly, they would pay 47c of tax. This means that for every dollar contributed to super the individual forgoes 53c in post-tax consumption while their super balance increases by 85c. The ratio of these (85c/53c) shows that, for each dollar of post-tax consumption forgone, this individual’s super balance will increase by $1.60.”

5. Comparison of super against other investments

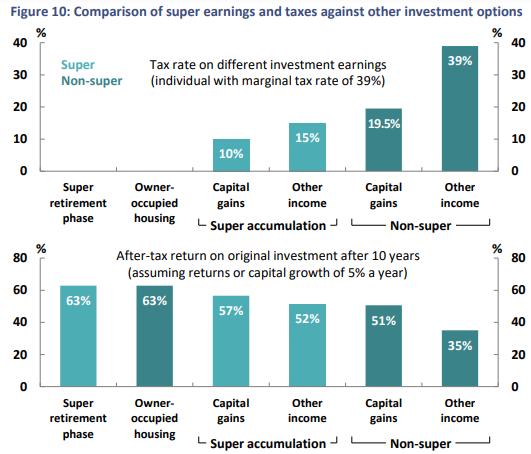

Investors frequently make comparisons between the benefits of using superannuation as a savings vehicle versus other structures, and this will increase with the new tax on balances over $3 million. As the PBO notes, super is not the only place where tax concessions are available.

The table below shows how the tax treatment affects returns over 10 years, based on someone in the tax bracket of 39% in 2022-23. It assumes all investments earn either a 5% return or 5% capital growth each year.

The PBO advises that holding money in a super pension versus a family home make the same returns after tax, based on these assumptions:

“Over a 10-year period, super earnings in the accumulation phase make a slightly higher after-tax return than capital gains outside of super, but a much higher return than investments outside of super that are taxed at a marginal rate of 39%. Owner-occupied housing, for which no tax is payable on the capital gains, makes a higher return, equivalent to the tax-free earnings in the super retirement phase.”

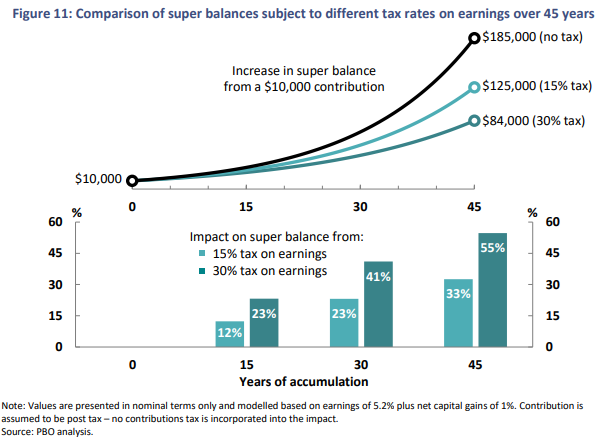

6. Dramatic impact of tax rates compounded over 45 years

While compounding earnings creates spectacular results over long periods, it also highlights the profound impact of different tax rates. When investing in super starts, the vast majority of the super balance comes from contributions, but over time, the compounding of earnings dominates. Thus the impact of the T or E taxes changes over time.

The PBO gives an example of an individual who makes a $10,000 post-tax contribution at the age of 22. If this individual retires at age 67 (45 years later), that $10,000 contribution has increased to $125,000 based on an average return of 5.2% plus net capital gains of 1%, taxed at 15%. If earnings were taxed at 30%, the final retirement balance would only be $84,000, or about one-third lower. If earnings were not taxed at all, their $10,000 contribution would increase the final balance by $185,000, nearly 50% higher than with a 15% tax and more than double the balance under a 30% tax.

Some final points of PBO emphasis

The PBO recognises that tax concessions are required to encourage people to save for retirement:

“Individuals usually prefer consumption today over consumption in the future. Tax concessions on super contributions provide some compensation to individuals for forgoing today’s consumption. But the tax concessions on contributions do not compensate individuals equally.”

The PBO also acknowledges significant changes already made to superannuation over the years, and in fact, that prior to 1988, withdrawals were taxed and Australia had an EET super tax system. It then moved to an TTT before today’s TTE system came in from 2007-08 when withdrawals became tax free. But the PBO does not favour any one structure, and states:

“In terms of the overall impact of taxes on final retirement balances across a working life, Australia’s TTE scheme is broadly equivalent to an EET scheme.”

Anyone advocating more taxes on withdrawals should therefore consider whether this means contributions and earnings should be taxed less, as it’s the complete picture through a lifetime of super saving that matters.

Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks. The full paper, How super is taxed, is provided by the Parliamentary Budget Office.