There’s an old saying that two wrongs don’t make a right. In the current refundable franking credits brouhaha, it’s possible that if Labor is elected, we will have been treated to three wrongs.

We have experienced:

- Wrong 1 - the introduction in 2007 by the Liberals of tax exemption of superannuation fund benefit payments to individuals aged over 60.

- Wrong 2 - the introduction in 2017 by the Liberals of the $1.6 million pension cap which attempted to claw back part of the Wrong 1 tax exemption for wealthier superannuants, but with added complexity.

- Wrong 3 - the proposed introduction in 2019 by Labor of the removal of franking credit refunds, in particular from superannuation funds.

Why can we say that the three wrongs don’t make a right? The answer is that, to the extent that an SMSF pensioner invests in Australian shares, the three steps together will leave that pensioner in a worse financial position than when superannuation pensions were taxable up until 2007.

This is the incredible result nobody talks about, but it isn’t the only reason.

For many SMSF pensioners with modest pensions, holding Australian shares for income rather than trading, the changes will even leave them worse off than had they been holding the same shares outside the superannuation system.

Current income outside super versus SMSF after Labor franking

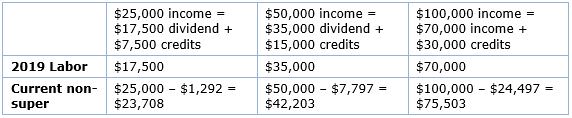

Before turning to the historical superannuation taxation regime, let’s compare the after-personal-tax positions for three different SMSF income levels under the Labor 2019 scenario with the current non-super taxation arrangements.

(The tax shown has been calculated at the personal tax rates applicable in the 2018/19 financial year, ignoring Medicare and any other variations that might apply in individual cases. https://www.ato.gov.au/rates/individual-income-tax-rates/)

In practice, there is no restriction on the amount of pension income that can be taken in any year beyond an age-related minimum. To compare like with like, I have assumed that net fund income is taken as a pension, although both lower and higher amounts could be taken, subject to the age-related minimum.

The reason that an SMSF pensioner is worse off inside super is because the Labor policy effectively results in a flat tax rate of 30% being applied to share income. In contrast, personal tax is levied at graduated rates with any individual’s average rate of tax being less than his or her marginal rate. An individual’s average tax rate doesn’t reach 30% until taxable income reaches about $180,000 (or about $140,000 with the 2% Medicare levy included).

It was better when superannuation pensions were taxed

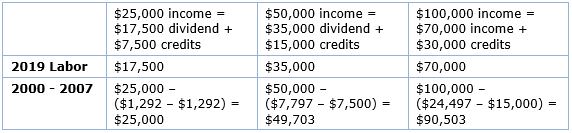

Now let’s turn to a comparison with the historical superannuation taxation regime. In the years until 2007, franking credits were refundable, but superannuation pensions were taxable.

It was a perfectly equitable arrangement and did not draw any criticism back then.

(Again, the personal tax rates are those applicable in the 2018/19 financial year, ignoring Medicare and any other variations that might apply in individual cases).

What is different in the personal tax calculations in the second table above is the deduction from personal tax of a 15% rebate (a rebate that still applies today for superannuation pensioners older than their preservation age but under 60).

This table makes clear that SMSF pensioners invested in Australian shares will be much worse off under the Labor policy than in the ‘bad old days’ when their pensions were taxed.

And further calculations show that the same conclusion applies pro-rata to those with anything above a slowly-increasing income-related allocation to Australian shares, i.e., many if not most SMSF pensioners.

Is the 15% rebate an undeserved concession for superannuation pensioners?

Let’s look at how the 15% rebate came about.

Prior to 1983, superannuation pensions were taxed in full as income (apart from any return of undeducted contributions). In contrast, superannuation lump sums largely escaped tax, which was why lump-sum tax was increased to 30% in 1983. Pensions remained fully taxed.

However, because of its gradual phasing-in, the 1983 lump-sum tax (levied at the personal level) would have taken years to raise significant revenue. Thus in 1988, superannuation fund taxation was introduced at the rate of 15%, specifically to bring forward half of the 1983 30% personal lump-sum tax, the rate of which was then reduced to 15%. Both contributions and investment income were legislated as taxable income.

But because the superannuation fund tax applied to all contributions and income, and not just the contributions and income used to ultimately finance lump sums, it was necessary to grant a corresponding reduction in tax to individuals becoming entitled to a superannuation pension. This was achieved by the granting of a personal 15% rebate, which recognised the pre-payment of brought-forward tax in respect of taxable superannuation pensions.

For example, if a taxable superannuation pension of $50,000 generated a personal tax liability of $10,000, then this was reduced by 15% of $50,000 = $7,500 so that the final tax payable was $2,500.

There are those who like to present any reduction in taxation liability as a concession. But in fact, a so-called concession may in fact be an anti-detriment provision, which is clearly the case for the 15% rebate in respect of taxable superannuation pensions.

In fact, it can be argued that the rebate is insufficient to provide full anti-detriment since:

- it is non-refundable, adversely impacting those on lower incomes; and

- it allows only for the tax on contributions and not that on investment income.

Conclusions on the best and fairest system

I believe the purest and fairest superannuation tax system was that operating between 2000 and 2007, when refunds on franking credits were granted to funds, but they were then taxed as part of the overall pension income when paid to the superannuation pensioner.

This perfectly equitable system was broken by the Liberals in 2007 when they made super payments tax free for the over-60s.

Not surprisingly, in recent times, governments have been looking at ways of reining in the cost of tax freedom of superannuation pensions. The 2017 $1.6 million cap, with its dauntingly complex administration, would never have been necessary had super pensions remained taxable.

Why are politicians unable to countenance the source of the perceived problem?

The real villain in this long-playing tragedy is not the refunding of franking credits to superannuation funds but the 2007 tax freedom of superannuation benefits to over 60s. Why is hardly anyone, including leading economic commentators, complaining about the cost to revenue of beneficiaries receiving retirement income free of tax?

Geoff Walker is a former Chief Actuary at the State Bank of New South Wales and winner of the 1989 JASSA Prize for published research on the implications of the then relatively-new dividend imputation system.