Last week, I explained three enduring principles laid out by Ben Graham, the father of security analysis and mentor of Warren Buffett:

- the ‘Mr Market’ allegory

- the ‘margin of safety’

- the market is a short term voting machine and a long term weighing machine.

What Graham described is something that, as both a private and professional investor, I have observed myself. Prices often diverge significantly from that which is justified by the economic performance of the business, but in the long term, prices eventually converge with intrinsic values. My definition of intrinsic value is the estimated actual value of a company determined through fundamental analysis without reference to its market value. I will explain the calculations further in subsequent articles.

This week, we compare estimated intrinsic value and share prices for some major Australian stocks to illustrate Ben Graham’s enduring principles, using data and graphics from skaffold.com.

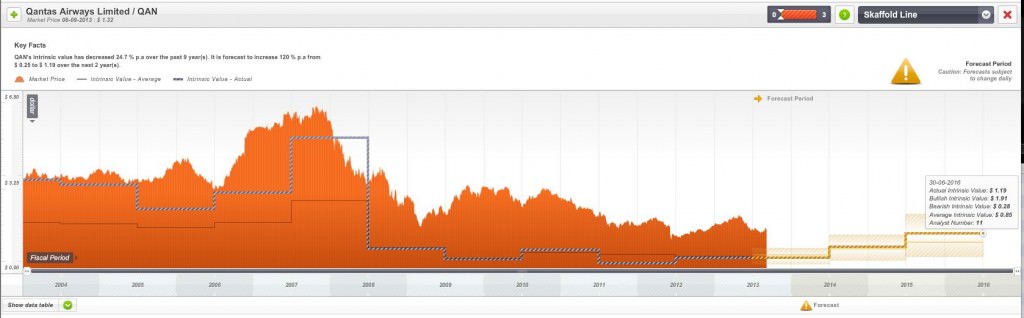

Have a look at the following chart. Figure 1 displays ten years of price and intrinsic value history for Qantas. You will notice that Qantas’ intrinsic value (the stepped grey line), which is based on its economic performance has, at best, not changed for many years. In fact, the intrinsic value of Qantas today is lower than it was a decade ago. And just as Ben Graham predicted, the long term weighing machine has also correctly appraised its worth (the actual market price is the orange box). The price today is also lower than a decade ago.

Figure 1. Ten years historic and three years forecast intrinsic values for Qantas (QAN)

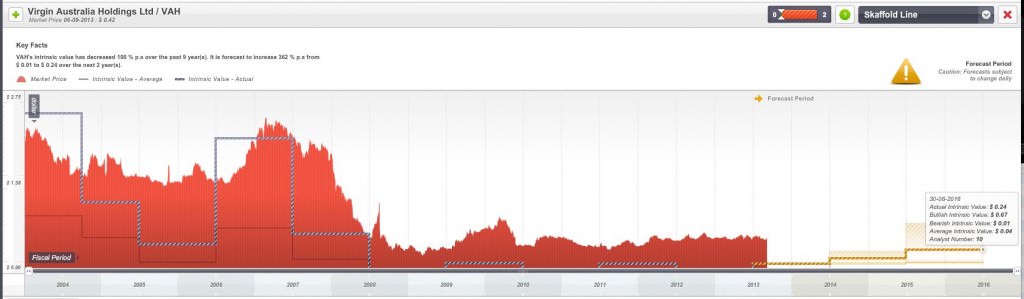

Airlines are a business with particularly challenging economics and whether run well or poorly have a long-term tendency to destroy wealth. Take a look at the Figure 2 for Virgin Australia.

Figure 2. Ten years historic and three years forecast intrinsic values for Virgin Australia (VAH)

Unless you can see a reason for a permanent change in the prospects of these companies, the long-term trend in intrinsic value gives you all the information you need to steer well clear. Irrespective of how hard the oarsmen of these business boats row, and no matter how qualified they are for the task, their rowing will always be distracted by the need to perpetually fix leaks in the boats’ sides.

Take a look at Figure 3. This time it’s a ten-year history of price and intrinsic value for Telstra. Sure, there have been short-term episodes of price buoyancy (such as the present affliction due to a bout of faddish infatuation with yield), but over the long run, the weighing machine has done and will continue to do its work. The intrinsic value of Telstra has barely changed in a decade, and neither has its price, and over time the share price will generally reflect the company’s worth.

Figure 3. Ten years historic and three years forecast intrinsic values for Telstra (TLS)

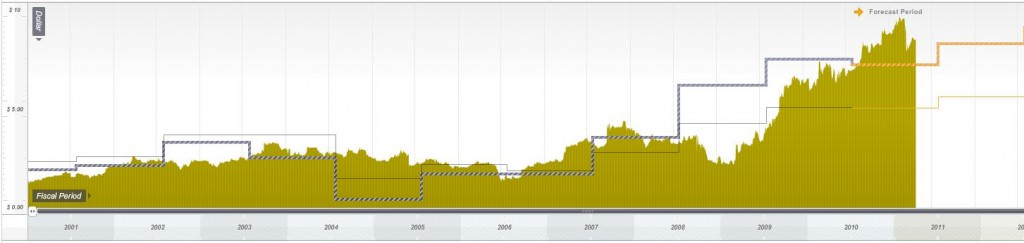

Finally, take a look at the change in intrinsic value of Oroton prior to and after Sally Macdonald joined the company as CEO in 2005/06 (she recently announced her resignation). Once again price and value show a strong correlation over longer periods of time. Prior to Sally’s arrival the price of Oroton tracked the somewhat benign performance of estimated intrinsic value. Then, from 2006 onwards, Sally’s effort at improving the value of the company, which continued to rise up until 2012, was also reflected in an expanding share price.

Figure 4. Ten years historic and three years forecast intrinsic values for Oroton (ORL)

I acknowledge that there are critics of the approach to intrinsic value that we follow. Indeed, I am delighted there are as critics are necessary for commercial reasons; not only do they help refine one’s ideas, but how else would we be able to find bargains in the market. If it was universal agreement I was after I would simply tell jokes to children.

Figures 1 through 4 (just four examples of those we have for every listed company) confirms what Ben Graham had discovered without the power of modern computing; that in the short run, the market is indeed a voting machine, and will always reflect what is popular, but in the long run, the market is a weighing machine, and price will reflect intrinsic value.

If you concentrate on long-term intrinsic values rather than allow yourself to be seduced by short-term prices, I cannot see how, over a long period of time, you cannot help but improve your investing. Ben Graham outperformed the market materially over an extended period of time. By abiding by his most popular edicts, you too are more likely to do likewise.

Roger Montgomery is the founder and Chief Investment Officer at The Montgomery Fund and author of 'Value.Able'.